Encores really bug some concertgoers. Why go through the motions of pretending the show is over one, two, three, or more times, only to return to the stage to play another song or two each time? Whose idea was this?

The answer is rooted in technology — or rather, the lack of it.

The genesis of the encore goes back to at least the 18th century, long before anyone could summon up music on demand. Without recorded music, the only way anyone could hear their favourite music was to wait for an opportunity to go someplace where it would be performed. Once the concert was over, it was over — unless the audience decided to hit the 1700s version of the “repeat” button.

The crowd yelled “Encore!” — French for “again.” In Italy, the cry was “Ancora!” These were demands by the audience (and more importantly, the performer’s wealthy patrons) to hear the most popular songs or portions of, say, an opera, one more time. And back then, these exhortations didn’t just happen at the end of the show. Shouts of “encore/ancora” (and alternately “une autre,” “un rappel,” “bis,” and “un’altra volta”) erupted several times during a performance in hopes of encouraging the orchestra to play a popular part of a piece again right then and there.

An example would be Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro. When it premiered at the Burgtheater in Vienna, the audience, including Emperor József II of Austria, one of Wolfie’s biggest fans, loved it so much that the orchestra was obliged to play certain portions and movements again and again and again. By the time everyone went home, the mid-performance and end-of-the-night encores — five the first night — had extended the opera to twice its intended length.

Not everyone was cool with this, however. At one point, European opera houses banned encores, saying that they were too disruptive. Even fanboy Emperor József got tired of the interruptions and less than 10 days after Figaro was first performed (and two days after a performance required seven encores), he issued a ruling that encores needed to be limited.

“To prevent the excessive duration of operas, without however prejudicing the fame often sought by opera singers from the repetition of vocal pieces,” he declared, “I deem the enclosed notice to the public (that no piece for more than a single voice is to be repeated) to be the most reasonable expedient. You will therefore cause some posters to this effect to be printed.”

Get daily National news

Eventually, Austria, Italy, and Germany issued outright bans on shouts for encores, something that eventually extended to New World establishments like the Metropolitan Opera in New York.

Some actually feared that such unruly behaviour would lead to disorder. They had a point, too. In 1887, a member of the audience was so annoyed that Italian conductor Arturo Toscanini refused to replay the tenor aria Cielo e mar from the opera Gioconda. A soldier in the audience then called him “arrogant” to which Toscanini replied, “You’re not right, you dog.” Honour insulted, Toscanini was challenged to a duel. It never happened.

But audiences insisted. While encores disappeared from the more prestigious venues, the practice continued where the working class gathered to hear less serious music. Over time, shouting for an encore was derided as uncouth and rude by the moneyed class. By 1900, the only places where one could enjoy an encore were music halls and vaudeville theatres. If one of the acts sang a hot song of the day — perhaps the latest hit from New York’s Tin Pan Alley — he/she might be spontaneously called upon to sing it again and again until the audience was satiated. Song pluggers — people hired by music publishers to promote freshly written pop songs — loved when this happened because it inevitably meant an increase in sales of sheet music for that song.

The tradition of encores got a big boost from Broadway. Plays and musicals that were well-received often saw the audience call the actors and singers back onstage to take an extra bow, hoping to tease out the high of the performance just a little bit longer. By the late 1940s, such callbacks were not just common but widely expected.

From there, the tradition bled over into the nascent world of rock’n’roll. Crowds clamoured for Elvis to keep going but he refused to do encores. Horace Hogan, the promoter of an Elvis show at the Louisiana State Fair on Dec. 15, 1956, needed to disperse an ecstatic crowd so he became the first to utter the now-famous phrase, “Elvis has left the building.”

When they became superstars, The Beatles refused to play the encore game as well. Then again, encores were impossible. Audiences were so cray that once they played their set, they were whisked away in a waiting car.

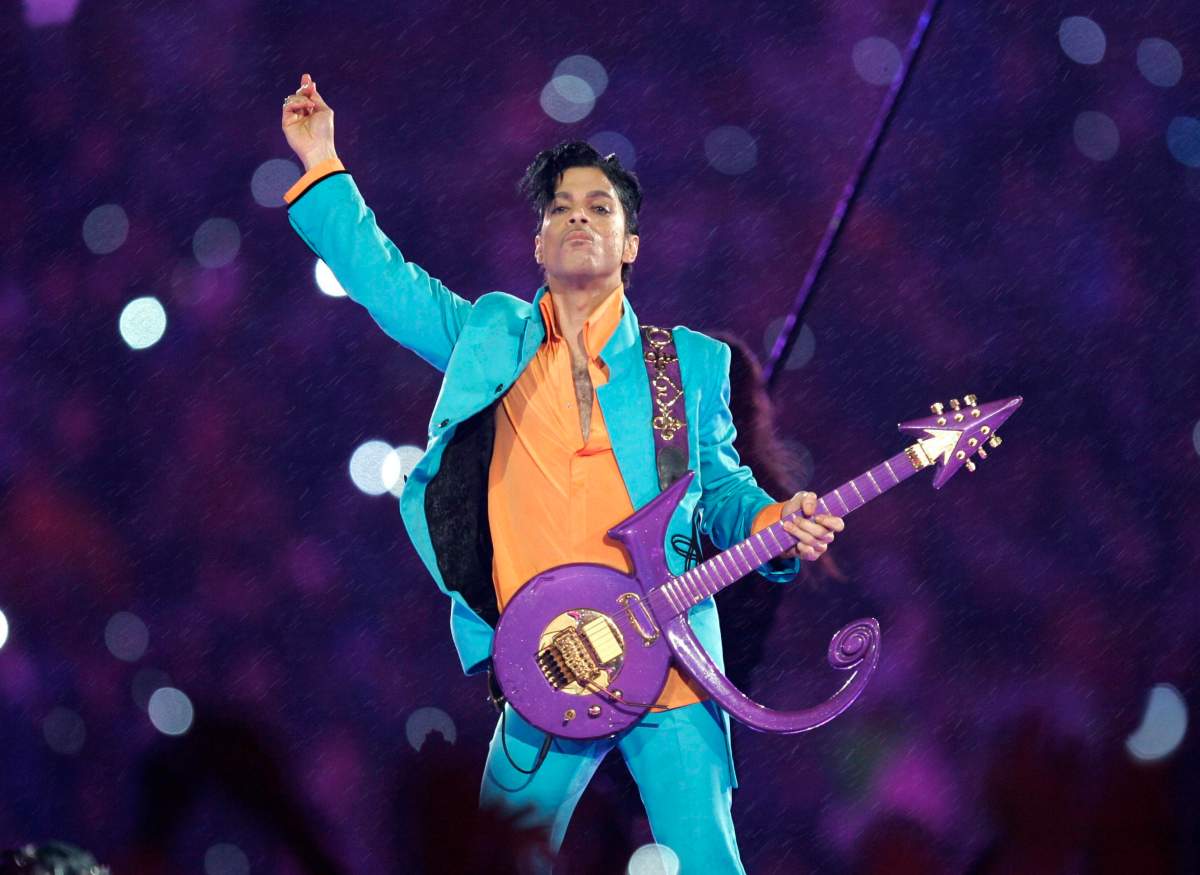

Eventually, though, the idea of encores became entrenched with many acts. Led Zeppelin, the Rolling Stones, and perhaps most of all, Bruce Springsteen, were only happy to play this game of hide-and-seek with the audience, even after playing for two hours or more. The Cure has been known to leave the stage and return up to five times. There’s documentation that Prince would play as many as seven encores. Bob Marley sometimes divided shows in half, leaving the stage about an hour into the performance only to come back on to play for another hour.

Yes, in some cases, it’s an artist’s ego that will drive multiple encores as they search for extra validation. Other times, it’s all part of the show. After a long set, a band might depart the stage for a quick break (water, oxygen, perhaps a few lines of cocaine) while the crowd buzzes about what big songs haven’t been played yet. The band then returns to play a couple of hits so that the evening ends on the highest note possible.

Note, too, that many encore performances come with special lighting cues and effects, making it plain that their return was always part of the plan. Both the artist and the audience is complicit in the charade, but few people seem to mind.

Not everyone, though. Elvis Costello used to have his sound guy blare loud music over the PA once he left the stage as a signal that it was time for everyone to leave. The message is clear: “You don’t have to go home, but you can’t stay here. Or maybe you can, but I’m gone.”

Emperor József would no doubt approve.

—

Alan Cross is a broadcaster with Q107 and 102.1 the Edge and a commentator for Global News.

Subscribe to Alan’s Ongoing History of New Music Podcast now on Apple Podcast or Google Play

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.