An Alberta regulatory body has turned down an application to expand a feedlot near a popular recreational lake south of Edmonton, saying the location wasn’t appropriate and would damage the local community.

In a decision released Wednesday, the Natural Resources Conservation Board has denied a plan from G&S Cattle to build a 4,000-head feedlot near the shores of Pigeon Lake, in the County of Wetaskiwin.

“I find that effects of this application on the community would not be acceptable, and that the proposed (confined feeding operation) would not be an appropriate use of this land,” wrote approval officer Nathan Shirley.

The decision was applauded by Catherine Pierce, head of the Pigeon Lake Watershed Association, which opposed the application and prepared many of the documents the board relied on.

“I couldn’t be more thrilled,” she said.

“This is a big win for the community and it’s due in large part to this community working together to make watershed management a priority.”

Greg Thalen, owner of G&S Cattle, was not immediately available for comment. Applicants denied by the board may request a review of its decision.

Get breaking National news

The slow turnover of water at the popular summer beach destination makes it uniquely vulnerable to the algae blooms.

Pigeon Lake is filled solely by runoff from surrounding land and is drained by one small stream. Studies have shown water that flows into the lake can stay there for up to 100 years, making it highly vulnerable.

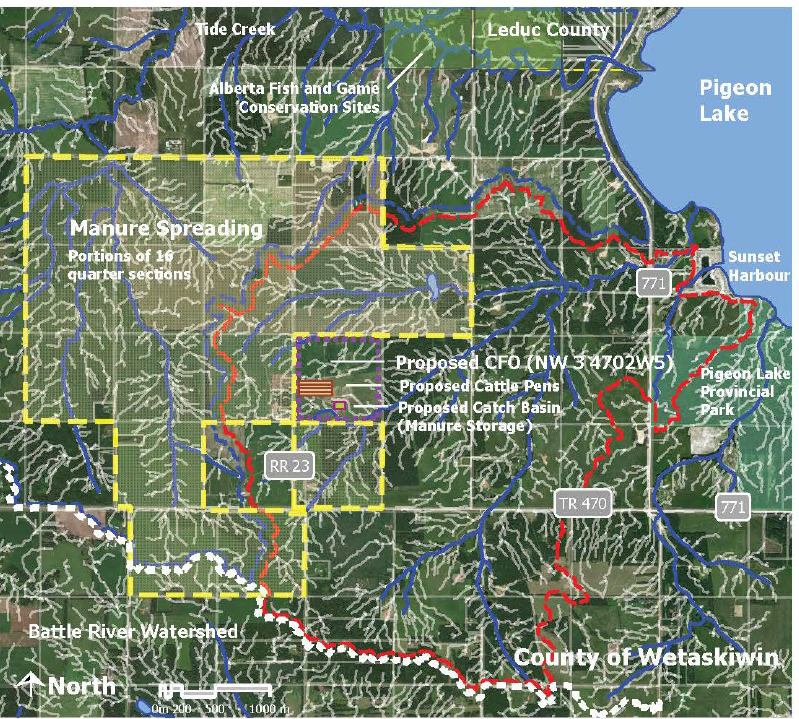

Thalen currently operates a 1,000-head feedlot near the lake. If approved, the expansion would have produced an estimated 36 tonnes of manure a day, which would be spread on about 1,000 hectares — almost six per cent of the lake’s entire watershed.

In the past, runoff nutrients from fertilizers and sewage fed foul-smelling blue-green algae blooms that clotted shorelines. The lake has also dealt with fecal bacteria.

Local residents have worked hard and spent millions of dollars to reduce fertilizer runoff and improve regional water treatment.

Although algae can still be an issue, the lake is home to about 5,800 seasonal and permanent residents and attracts about 100,000 visitors a year to its leafy setting, beaches, boating and fishing.

The watershed association spent 10 years developing a management plan that was signed by a dozen local municipalities. Area First Nations have also supported it.

The breadth of support for that plan, which excludes new feedlots, was key to the board’s decision, Shirley wrote.

“The (plan) was adopted as a guiding principle for future land uses in this area. It is, therefore, my opinion that the (plan) is key in the assessment of whether the (feedlot) would be an appropriate use of land.”

Pierce said that proves organized and well-researched local input can affect regulatory decisions in Alberta.

“The Agricultural Operations Practices Act is still 20 years out of date and we have to be prepared to challenge the status of that act in order to highlight modern-day science and our understanding of how we can best protect our freshwater sources.”

The proposed feedlot was highly contentious and the board received many more responses to the application than usual.

A board spokeswoman said it had 388 respondents, including individuals, summer villages, Indigenous communities, corporations and other organizations by its deadline of April 7.

The board continued to receive responses after the deadline.

The day the decision came saw 30 C temperatures and bright sun across much of the province, including Pigeon Lake.

“I’m going to the lake,” Pierce said.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.