A group of student scientists in Halifax are hoping to get the next generation of Black, Indigenous and People of Colour (BIPOC) youth interested in nature.

Diversity of Nature is a scientific outreach organization led by BIPOC graduate students at Dalhousie University.

“Growing up as racialized folks, myself and my co-director Suchinta Arif, found that we didn’t really get a lot of opportunities to meaningfully participate in ecological activities, so really getting exposed to biology,” said Diversity of Nature cofounder Melanie Massey.

“So we felt that as scientists in this position of privilege, one of the best things we could do to help elevate racialized members of the community was to share science with them.”

The group offers free workshops and programming dedicated to youth with the goal of increasing BIPOC representation in the natural sciences. They hope to break down barriers and provide role models for racialized youth.

“Often in science, we tend to see one type of person reflected as a scientist,” said Massey. “What we want to show these kids is that anybody can be a scientist, even people who look like them.”

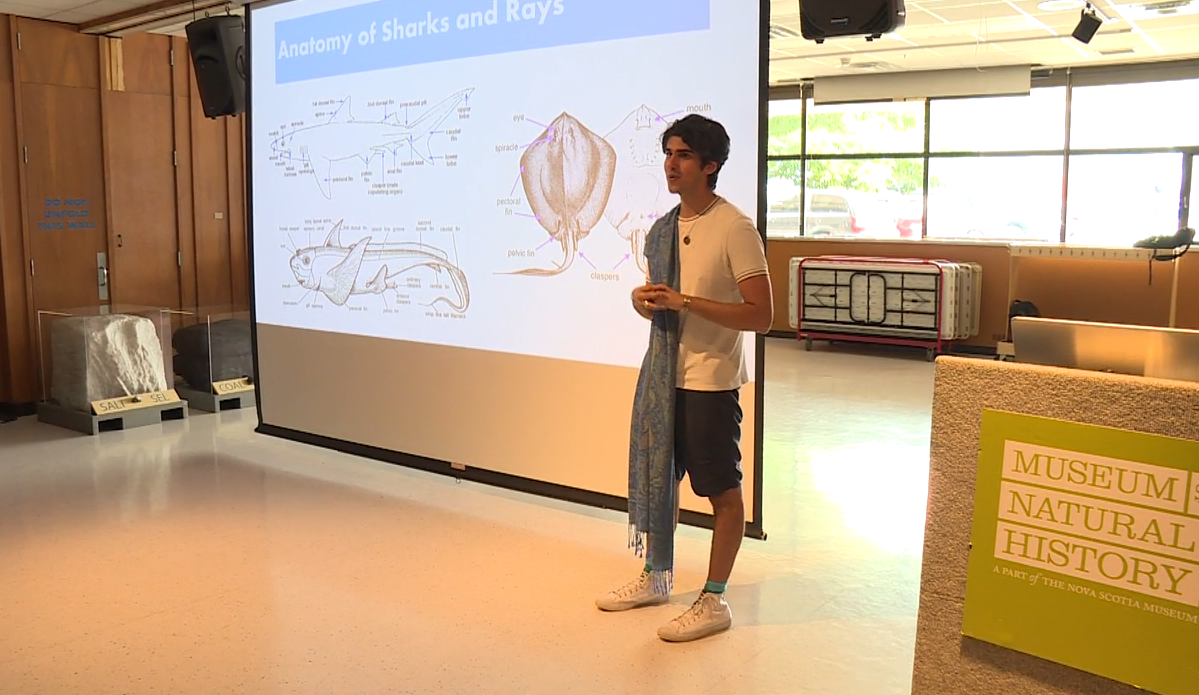

On Wednesday, Diversity of Nature hosted a workshop on sharks, where youth were able to get hands-on experience handling and dissecting the sea creatures.

Brothers Hayden and Hayven Joseph took part. The pair say they’ve both been fascinated with sharks since as long as they can remember.

“It was really fun, because it was my first time opening one,” said 11-year-old Hayven.

“I dissected a shark, I basically saw it’s liver and it’s stomach,” said Hayden, 13. “It was pretty fun,” adding this experience was a first for him too.

Undergraduate student Aaron Judah lead the shark dissection workshop.

“Being able to see the wonder in those eyes — the wonder that I still have and the wonder that I had as a kid — it reminds of seeing it for the first time, and seeing them really going for it gives me hope that we have a good and blue future for our planet,” said Judah.

Several ‘sizable’ barriers

Get breaking National news

Judah said as a diverse scientist who’s part of the LGBTQ community, while he’s had mainly positive experiences he’s also faced microaggressions along the way.

“I’ve been told in the past: ‘Let the more masculine guys go and tag the animal.’ So it’s kind of that very macho-esque type feel,” he told Global News.

“A lot of us have had different experiences, whether it’s not being fully trusted with stuff or being underestimated, but now we have amazing leaders around the world from these communities really showing just how powerhouse diverse scientists can be.”

Eric Archer is the program lead of marine mammal genetics at the NOAA Southwest Fisheries Science Center in La Jolla, Calif. He said while the field internationally is diverse, from a North American perspective, it’s dominated by white people.

“People of colour within that North American contingent, there’s very few,” he told Global News.

“We don’t have a lot of strong representation. There are people that are doing good work but I think it’s hard for them to get recognized.”

He said there are several “sizable” barriers to entering the discipline, including a reliance on unpaid internships, as studying marine mammals is inherently difficult and expensive, requiring gear, boats, people and time.

“There’s a lot of people that could potentially be interested in the field, but they don’t have the resources to make that entry step,” he said, adding those that can volunteer their time for free are then a step above those who can’t.

“And then that disparity just keeps on growing. So it becomes this self-selecting thing of the socioeconomic classes that can afford to get that experience — that is one of the critical first steps — and they then become the ones that get the few jobs that are available … and then that closes the door for the people who don’t have the resources.”

In 2020, he and more than 700 marine mammal researchers signed a petition taking a stand against unpaid positions, saying it’s a barrier that unfairly targets some, presenting barriers to diversity and inclusion.

“It’s not always obvious why it is an issue. I would not be here if I didn’t have a family that had the resources to let me volunteer,” he said. “And most of my colleagues have similar stories. Therefore, we think of it as a normal thing, but you forget the ones that you don’t see around you.”

“I think we miss out on new ways of seeing these animals and therefore understanding the ecosystem in the world if those experiences are limited to a certain group of people or a small subset of people.”

Making the change

Massey said she had a similar experience while completing her undergraduate degree.

“As many of my friends from wealthier backgrounds were able to volunteer their time in labs, I was lifeguarding,” she said. “And this is a story that I’ve heard from many racialized scholars and scholars from low-income communities.”

It’s why all educators who host workshops through Diversity of Nature are compensated, she said, in an effort to combat “hidden labour.”

“It’s work that often falls on minorities, and it’s important for the functioning of any field, including science, but people tend to not be paid for this work and they tend to not be recognized.”

An opportunity that not only provides paid opportunities for current science students, but free experiences for potential future ones.

“It is really important that there is representation from different groups within science, especially when we’re undergoing this climate crisis now, and it’s likely to impact racialized communities more than it’s likely to impact majority wealthy communities so it’s really important that we have those voices advocating for those communities,” she said.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.