Researchers believe they may have found ground zero for the deadliest plague in human history, the Black Death — pulling the veil off a mystery that has been shrouded for nearly 700 years.

A paper published in Nature on Wednesday details how a team of archaeologists and geneticists sequenced the genome of plague bacteria found in medieval corpses that predate the first plague outbreaks in Eurasia. The make-up of this ancient bacterial DNA has led researchers to believe it was the origin for almost all subsequent strains of bubonic plague.

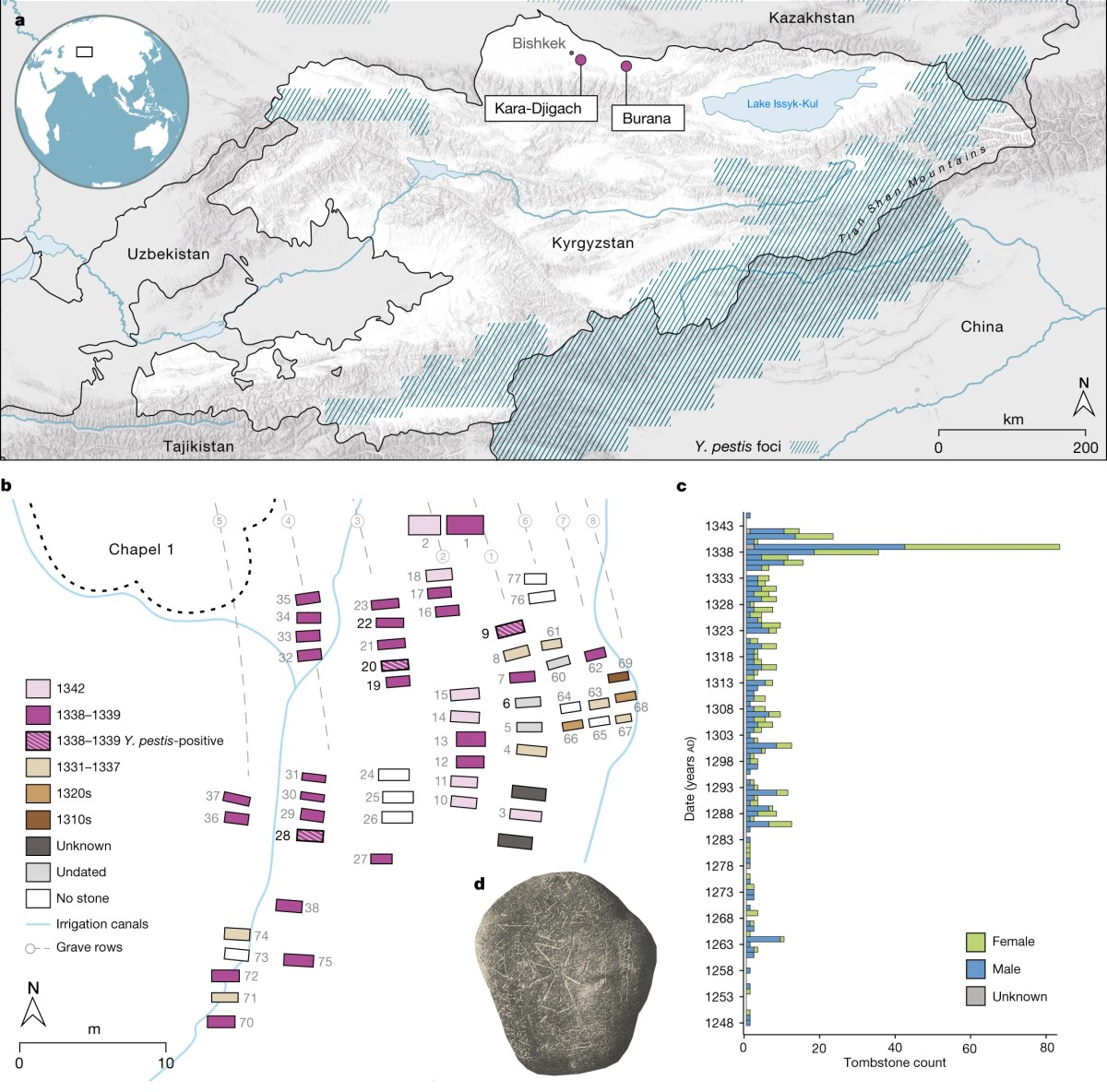

Samples of this original Yersinia pestis bacteria, the pathogen that causes bubonic plague, were found in northern Kyrgyzstan, in villages that were along the old Silk Road trade route in Central Asia.

The study began several years ago when Philip Slavin, an economic and environmental historian for the University of Stirling, came across records that a pair of 14th-century cemeteries had a significant amount of tombstones dated from 1338 to 1339. Ten of these tombstones explicitly referenced pestilence.

This was unusual because, prior to this study, the earliest deaths associated with the plague were in 1346 in the Crimean Peninsula.

“When you have one or two years with excess mortality, it means something funny is going on there,” Slavin said at a news conference.

The cemeteries are known as Kara-Djigach and Burana, and are situated in the foothills of the Tian Shan mountains. The burial grounds once serviced a medieval Nestorian Christian community in the Chu Valley but were excavated in the late 1800s. The bodies were all moved to St. Petersburg, Russia.

Led by archaeogeneticist Maria Spyrou, the research team sequenced DNA from the teeth of seven people whose bodies were recovered from the two sites. Three of the bodies from Kara-Djigach still contained Yersinia pestis.

Get daily National news

By reconstructing two full Y. pestis genomes found in the ancient bodies, the researchers were able to determine that they are the direct ancestors of strains that sparked the Black Death pandemic that ravaged its way through Europe, Asia, the Middle East and North Africa.

A man who died in 2011 from a strain of Y. pestis was also linked to this original bacteria. The team believes their ancient DNA is also the ancestor of most Y. pestis strains that are still present today.

“Our finding that the Black Death originated in Central Asia in the 1330s puts centuries-old debates to rest,” Slavin said of the study.

“It is like finding the place where all the strains come together, like with coronavirus where we have Alpha, Delta, Omicron all coming from this strain in Wuhan,” says Johannes Krause, a co-lead of the study and a palaeogeneticist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

The Silk Road was an overland route for caravans carrying a panoply of goods back and forth from China through the cities of Central Asia to points including the Byzantine capital Constantinople and Persia. It also may have served as a conduit of death if the pathogen hitched a ride on the caravans.

“There have been a number of different hypotheses suggesting that the pandemic may have originated in East Asia, specifically China, in Central Asia, in India, or even close to where the first outbreaks were documented in 1346 in the Black Sea and Caspian Sea regions,” Spyrou said.

“We know that trade was likely a determining factor to the dispersal of plague into Europe during the beginning of the Black Death. It is reasonable to hypothesize that similar processes determined the spread of the disease from Central Asia to the Black Sea between 1338 and 1346,” Spyrou added.

The region in northern Kyrgyzstan where this early form of the plague can be traced to was likely involved in international trade. Fine goods such as pearls, coins and clothing from foreign locales have been uncovered there so it may have been a stopover location for long-distance caravans.

Pandemic origins are hotly contested, as evidenced by the debate over the current COVID-19 pandemic’s emergence.

The Black Death was the deadliest pandemic on record. It may have killed 50 to 60 per cent of the population in parts of Western Europe and 50 per cent in the Middle East, combining for about 50 to 60 million deaths, Slavin said. An “unaccountable number” of people also died in the Caucasus, Iran and Central Asia, he added.

Bubonic plague, untreatable at the time but now curable using antibiotics, caused swollen lymph nodes with blood and pus seeping out, with the infection spreading to the blood and lungs.

Rodents are the natural reservoir for Y. pestis, and humans develop bubonic plague only when a vector such as a flea passes on the infection. Krause suspects that humans’ close contact with infected marmots sparked the Kyrgyzstan epidemic, whereas immunologically naive rat populations in Europe fuelled the Black Death.

“We found that the closest living relatives of that Y. pestis strain that gave rise to the Black Death are still found in marmots in that region today,” Krause said.

— With files from Reuters

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.