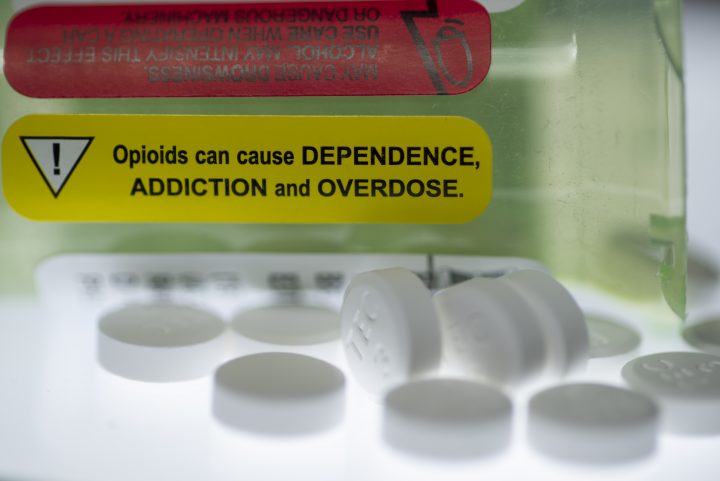

Researchers say a new treatment that is less intrusive and more accessible than what has been offered to patients struggling with opioid addiction has been shown to be just as effective.

Currently, patients with opioid use disorder can be asked to show up at a pharmacy every day for two to three months to begin treatment with methadone or morphine, which have to be taken under close supervision.

“It takes a high level of motivation to follow those treatments,” said Didier Jutras-Aswad, a Université de Montréal professor of psychiatry and lead author of a study published Wednesday in the American Journal of Psychiatry.

“But we also have people that were really motivated, or people that might be really motivated to be treated, but that don’t want to embark on this type of treatment knowing how demanding it is.”

He noted that those struggling with addiction are often in precarious and vulnerable situations.

The new study shows it is possible to offer a more flexible treatment at home without reducing the chance of success.

The Public Health Agency of Canada reported that more than 5,386 Canadians died from an opioid overdose between January and September 2021, which amounts to about 20 deaths per day. In 2018, before the COVID-19 pandemic, there were 12 deaths per day.

Get weekly health news

The new treatment, developed in a clinical trial through the Canadian Research Initiative in Substance Misuse, is based on prescribing buprenorphine-naloxone, also known by the commercial name Suboxone.

Between October 2017 and March 2020, the clinical research team recruited more than 270 volunteers in seven hospitals in Quebec, Ontario, Alberta, and British Columbia. Participants’ average age was 39, and 35 per cent of them were women. All were struggling with opioid addiction from either prescription or illegally produced drugs such as morphine, oxycodone, or fentanyl.

Patients were randomly divided into two groups, with half receiving methadone under close supervision in a pharmacy and the other half receiving Suboxone, which could be taken mostly at home. Both groups were asked to undergo treatment for 24 weeks.

“(Suboxone) is a little less strong than methadone and it’s often associated with less risk of overdose,” Jutras-Aswad said. That fit with the researchers’ proposed model of care in which the level of supervision was reduced.

Jutras-Aswad said researchers recommended that after the first two weeks, patients could continue the treatment with Suboxone unsupervised at home for one week — requiring just one visit to the pharmacy. Eventually, pharmacy visits were spaced out to two per month.

He said the study aimed to determine whether a more flexible treatment, with much less supervision, would be as efficient in reducing drug use as the current methadone treatment.

“’Our study showed that buprenorphine was not inferior to the methadone treatment for people that took it unsupervised, with even a trend showing buprenorphine is a little bit more efficient than methadone,” Jutras-Aswad said. He added that buprenorphine also offers greater flexibility than methadone in the event that a change of treatment is necessary.

“It’s no small thing to have to go to the pharmacy every day,” Jutras-Aswad said. “I think this is a winning model that really allows to respond to a catastrophic situation.”

Comments