By

Jules Knox

Global News

Published June 15, 2022

16 min read

A social worker in Kelowna has admitted to fraud involving hundreds of thousands of dollars from the B.C. government, and leaked ministry documents suggest how he was able to get away with it for years.

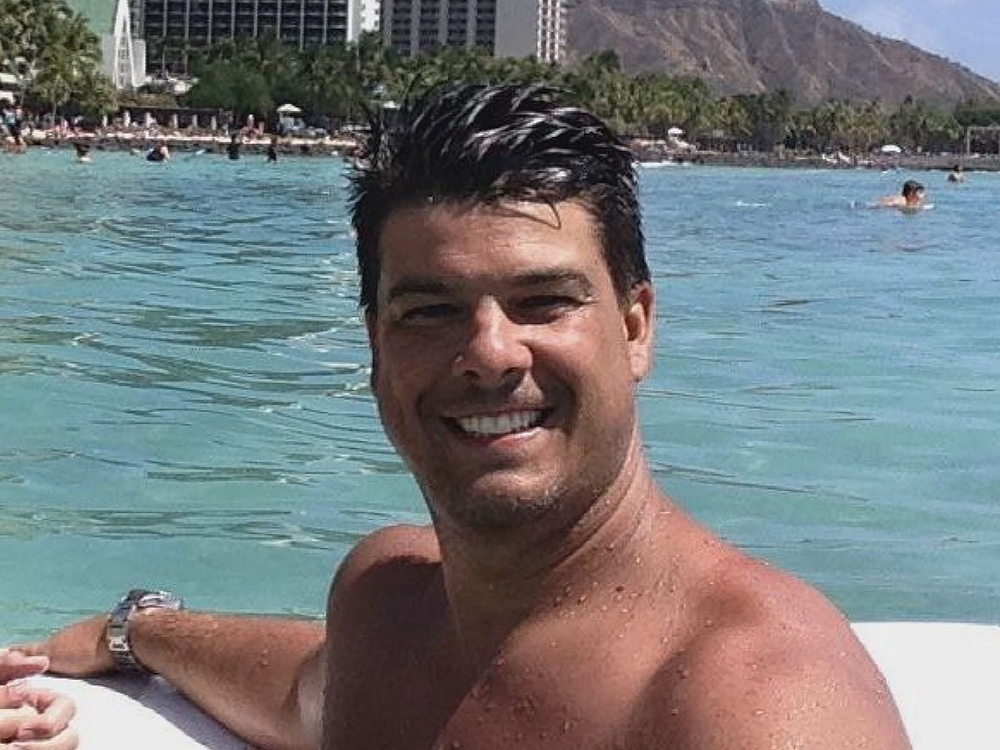

Robert Riley Saunders was accused of embezzling $354,283 from children in foster care after his boss Siobhan Stynes went away on holiday over Christmas in 2017. The government later upped its estimate to more than $460,000.

Internal documents suggest that another social worker stepped in to fill in for Stynes, who would typically be responsible for signing off on Saunders’ paperwork.

It didn’t take Andrea Courtney long to flag problems with Saunders’ documentation, according to a ministry report. Courtney declined an interview for this story, as did Saunders.

According to internal documents, Courtney said Saunders came in with a stack of papers for her to sign.

She noticed that a child in jail was receiving $579 for rent. According to a report for the ministry, Courtney said Saunders then told her it was a mistake.

That prompted Courtney to start digging further.

She took the files to office manager Patty Thickson, who also noted that they didn’t look right, according to ministry documents.

Courtney told investigators for the ministry that Saunders then started blowing up her phone with calls. She didn’t answer until later when he allegedly asked her to “just leave it alone” and stop looking into it.

Courtney and Thickson reported their concerns to the ministry.

Saunders was technically on vacation at the time, and the director of operations told him not to go into the office.

According to internal documents, staff reported that he went into the office anyway, ripped up the letter telling him to stay away, and started shredding other documents.

Saunders, who had been with the ministry for more than 20 years, was then suspended with pay upon his return from vacation on Jan. 8, 2018.

Stynes, his boss, was “reassigned” to other duties and her team-lead privileges were revoked as the matter was investigated, according to emails.

Two weeks later, ministry officials became aware that Saunders had put his house up for sale. On Feb. 23, 2018, Saunders suddenly walked out of a meeting with investigators hired by the ministry.

He eventually returned for another interview the next week.

A ministry report later found that Saunders opened joint bank accounts with youth in his care and then transferred the funds to his own account.

He used the money as disposable income, for bills and to pay for things for his own children in “trying to buy their affection,” the report says.

According to internal documents, other social workers had previously questioned Saunders’ lavish lifestyle, which included multiple trips to Las Vegas, as well as a new boat, truck and house. A ministry report also says he bought his teen son a BMW.

Government documents suggest that Saunders’ base salary would be somewhere around $70,000 a year, or $5,700 a month. At times, he nearly tripled his monthly income by supplementing it with stolen funds, ministry documents allege.

An early report to the office of the comptroller general suggests that Saunders deposited 22 cheques totalling $12,580 at Interior Savings Credit Union on Nov. 29, 2017.

On Dec. 20, 2017, he appeared to deposit 20 cheques totalling $11,580, according to the report. That was one day before Courtney would notice something was wrong.

Although the amounts increased with time, it’s a pattern that appears to have been ongoing for years.

Since Jan. 1, 2014, Saunders appeared to cash more than $47,000 in cheques at Interior Savings Credit Union under one youth’s name, according to internal documents.

The report for the ministry also suggests another nine youths also appear to have amounts ranging from more than $10,000 to approximately $44,000 cashed.

One of the teens was in custody, yet Saunders was still able to cash $11,041 in his name over a one-year period, according to the report’s findings.

There are questions about how nobody caught the fraud for years.

Interior Savings Credit Union was later named in a civil class action suit launched by youth in Saunders’ care. A civil claim filed by the victims argued that the credit union knew, or should have known, that Saunders moved the money from a joint account to his own personal account, using the funds for himself.

The report to the office of the comptroller general found money was often transferred out to Saunders’ personal account on the same day as the deposit, leaving a balance in the accounts of typically less than $20.

Eight of the joint accounts were closed by Saunders on the day he was suspended.

Interior Savings denied any liability, arguing Saunders made false and misleading statements to staff.

In December 2020, after a lengthy police investigation, Saunders was eventually charged criminally with 10 counts of fraud over $5,000, theft, breach of trust and using a forged a document. No other ministry employee was charged in relation to the fraud.

Saunders would later plead guilty to just three of those charges: one count of fraud over $5,000, breach of trust and using a forged document.

According to a ministry transcription of an interview with Saunders, the social worker said he was going through a divorce and having a financial crisis when he discovered a hole in the system.

Saunders said he divorced around 2011, although he initially claimed the misappropriation of funds did not start until 2014.

“I don’t want to piss off my employer here, but the employer turns a blind eye to what we do to make sure that these kids are accountable, putting them at a friend’s place, or putting them at a known ‘crack shack’ or whatever,” Saunders said, according to a ministry transcription of his interview in March 2018.

The ministry report said Saunders told investigators he would have never issued “that kind of money” to the youth he works with as he felt they would have spent the money on drugs or alcohol.

“He found there was not a lot of attention paid to the processes and no one ever questioned the payments despite case consultations and reviews,” according to the ministry’s initial findings.

The report also noted “Mr. Saunders was often the guardian of the very youth whose names he was using to pursue his own financial gain,” and the children in his care were exceptionally vulnerable.

According to a ministry investigation, Saunders indicated that he acted alone and did not receive assistance from anyone else.

In a statement for this story, the Ministry of Children and Family Development said that as it is a criminal matter, it is unable to comment on the specifics of the situation.

The Ministry of Children and Family Development opened its own internal investigation into how Saunders’ fraud could have happened, and it named Saunders’ team leader Stynes, office manager Thickson and team assistant Kim Burnett as respondents in the matter.

Burnett was later dropped as a respondent, and the ministry ultimately found that Stynes and Thickson were not complicit in the fraud.

However, emails from the finance department to Saunders, Stynes and Thickson over the spring and summer of 2017 flagged irregularities in the social worker’s paperwork. Another email shows that Saunders had been warned that he was not allowed to both request and authorize a payment.

But it would be months before the ministry realized he was misappropriating funds. By then, internal documents suggest he stole at least another $56,000.

Thickson, who was named as a respondent, was one of the people who flagged Saunders’ misappropriation of funds to the ministry in December 2017. About a week prior to noticing issues with the social worker’s incomplete paperwork, she had also questioned why Saunders was requesting a gift card for a youth who was in jail.

A subsequent investigation found that Saunders was able to request and authorize cheques for youth under an independent living arrangement, a program where the ministry gives teens money for rent and clothing.

“The system will allow the requestor to be the same as the spending authority, but policy does not,” according to a January 2018 ministry report.

The ministry report states that according to its policy, Saunders’ team leader should have been signing off on the cheques. He worked under two different team leaders at separate times between 2014 and 2017.

Stynes was Saunders’ boss when he was caught.

In court, the Crown told the judge the means by which Saunders carried out his fraud was “obvious.”

“There was no effort on Mr. Saunders’ behalf to effectively conceal that he received that money. It went through the bank accounts that he opened with youth in his care,” prosecutor Heather Magnin said.

During an interview with ministry representatives in March 2018, investigators asked Saunders who he thought should be responsible for paying attention to the process.

“I think it would start with my team leader,” Saunders said, according to ministry notes. “In all fairness to the two team leaders that I have had, I don’t think they know about the process.”

Court later heard that when the ministry investigated back until 2011, it found that a third team leader was also in charge of Saunders while the fraud appeared to be ongoing.

Under cross-examination in court, Saunders agreed with the Crown that he had identified multiple ways in which he could get funds to himself rather than to the youth.

Saunders agreed that he “possibly” had requested funds for a teen’s driving lessons and then issued two cheques: one for the youth’s driving lessons and then a second payment for himself.

According to ministry notes from an interview with Courtney, shortly before the fraud was discovered, the day before Stynes left on Christmas holidays, she spoke to Courtney, who would be in charge during her absence.

Courtney said Stynes was upset that Thickson, the office manager, was on Stynes’ case about Saunders’ incomplete paperwork, according to ministry notes.

Courtney also said that Stynes was meticulous with paperwork, according to ministry notes, and that there was no explanation as to why she would not be supervising Saunders’ files the same as other social workers.

Stynes claimed she was unaware that the cheques were being requested and did not approve them, according to notes from her interview with ministry investigators.

Meanwhile, internal ministry documents suggest that other employees at the office were frustrated that Saunders appeared to frequently leave work early in the afternoon.

Staff appeared to suggest to ministry investigators that Stynes was defensive of Saunders.

While documents suggest that staff raised concerns that Saunders was often absent from work in the afternoons, documents indicate Stynes responded during her ministry interview that she managed each of her employees differently. According to a ministry transcript, she said she had difficult conversations with Saunders, as she did with other staff.

Meanwhile, in court, Saunders took the stand during a Gardiner hearing, which is held when the Crown and defence disagree on the facts of a criminal case.

He admitted that he took the funds fraudulently, but argued that the youth who were supposed to be receiving the independent living cheques were mostly in foster care or living with family, which means they weren’t actually eligible for the payments.

Stynes told ministry investigators that because the youth were placed in homes, and thus ineligible for money to help with rent and utilities, she wasn’t aware Saunders was writing cheques to the teens under the independent living program.

According to a ministry interview transcript, director of operations Cheryl Beauchamp told investigators that the team lead and office manager should be the people responsible for preventing independent living cheques from being issued to clients who are not eligible for them.

“The team leader would be expected to consult on each of the files. They should know where the child is, whether they are in care,” Beauchamp said, according to the transcript. “You should be able to ask about any family in the office, the team leader should be able to tell you.”

Beauchamp also noted that the office manager printing cheques should see a pattern and questioned why Thickson didn’t see a problem sooner, according to ministry interview notes.

Notes from an interview with ministry investigators report that Thickson believed Burnett, a relatively new assistant, printed most of the cheques.

Thickson told investigators she had spoken to Stynes numerous times over a two-year period about Saunders’ incomplete paperwork, according to a ministry transcript of the office manager’s interview.

She added that while she wasn’t sure if her role in the administration of cheques was consistent with ministry practice, it was the way it had always been done, according to ministry notes.

Neither Stynes nor Thickson responded to an interview request for this story.

As for Burnett, according to internal documents, she resigned sometime around April 2018, a few months after Saunders’ fraud had been discovered. Ministry employees noted that meant she could no longer be questioned as a respondent in the case.

According to notes made by a ministry employee, Burnett said she did not think she had useful information and later declined an interview with the ministry. She also declined Global News’ request for comment.

The fraud discovered in late 2017 wasn’t the first time Saunders had been in trouble for alleged financial irregularities.

It turns out that the ministry had flagged and documented an alleged problem with Saunders more than a decade ago.

In a letter to Saunders following an apparent meeting with him in December 2004, a ministry representative claimed that he had engaged in a perceived conflict of interest.

Saunders allegedly personally withheld a client’s money and deliberately didn’t involve a third party to oversee a client’s financial transaction.

At the time, Saunders was working with high-risk youth.

Saunders was given a written reprimand and warned that if there were any similar breaches in the future he could face dismissal.

Five months later, an employee appraisal form found that Saunders was “suitable for promotion at this time.”

While the glowing employee review was filled out by a different boss, the same person who wrote the reprimand letter signed off on the appraisal form.

MNP, the company hired to investigate the fraud, was instructed to review financial irregularities dating back to Jan. 1, 2014.

A ministry report completed in March 2018 found that “there was evidence to suggest Mr. Saunders’ conduct began earlier than the timeframe reviewed by MNP and that he may have had accounts at other financial institutions.”

“A limited review of the financial data indicates that the payment pattern extends to before the period of review,” it suggests.

The ministry later appeared to investigate at least some financial irregularities dating back to 2011, although it did not specifically respond to Global News’ request for comment on the review period.

Internal ministry documents also suggest that some youth reported Saunders had asked them to open a joint account at TD Bank in Kelowna’s Rutland neighbourhood.

A review of cheques issued for $579, which is the amount associated with fraudulent cheques at Interior Savings, indicate that $16,212 were deposited in accounts at TD, according to a report.

However, investigators said that Saunders said he could not recall any joint accounts at TD.

The ministry report said that Saunders appeared to be remorseful and characterized himself in his interview as an “open book.”

“Investigators did note, however, that Mr. Saunders only admitted and acknowledged conduct where he was already aware of the evidence against him,” the ministry report said.

“When Mr. Saunders was asked about these matters he said he was unsure when he began to misappropriate funds but felt it was around 2014 (the beginning of the timeframe reviewed by MNP) and maintained it was only at Interior Savings,” according to the ministry report.

A report for the ministry said that TD Bank had not been contacted to investigate further as of March 2018.

When asked if the ministry had followed up with TD Bank, a government spokesperson would not address the specifics of the situation, saying it was a criminal matter.

Although Saunders has already pleaded guilty, TD Bank responded that it cannot provide any comment because the case is currently before the court.

In an October 2018 report, the ministry decided Stynes and Thickson “were not aware of, or complicit in, Mr. Saunders’ misappropriation of ministry funds.”

It did note that their involvement was inconsistent with ministry financial policy in some areas.

“Based on evidence provided and a balance of probabilities, investigators found that Ms. Stynes and Ms. Thickson were not involved in the approval of the independent living allowance payments improperly requested by Mr. Saunders,” according to the ministry’s investigation report.

However, the report did find that if Stynes had “discharged her duties as (a) cheque signing authority in a manner consistent with ministry policy, it is unlikely

Mr. Saunders would have successfully misappropriated ministry funds through independent living assistance cheques.”

The October 2018 ministry report also said that Thickson didn’t verify the necessary supporting documentation was attached to the payments in accordance with ministry policy. However, investigators also noted that Thickson appeared to follow practices that were in place from before the time that she became the office manager.

After the preliminary investigation had wrapped, the ministry sent an urgent email to the University of Manitoba in March 2019 asking if Saunders had ever earned his degree.

Staff only realized his credentials might be fake after a class action suit had been launched against Saunders, and one of the plaintiff’s lawyers alleged he had faked his degree.

“It is my statutory duty to investigate this latest allegation as it is relevant to the service he provided to children and families over his 23 year career, and potentially the harm he may have caused them,” a ministry employee wrote in an email to the university.

According to the email chain, the ministry believed he obtained two undergraduate degrees from the University of Manitoba: a Bachelor of Arts in Psychology in 1992 and a Bachelor of Social Work in 1994.

However, according to documents, the institution responded that although he attended the university, he did not earn either degree.

A judge later approved a multi-million dollar class action lawsuit against the Ministry of Children and Family Development. There were more than 100 potential victims, and they were mostly Indigenous.

In the settlement agreement, the province admitted vicarious liability for the harm that Saunders caused children in care.

“This harm includes neglect, misappropriation of funds and failure to plan for the children’s welfare and, with respect to Indigenous children, failure to take steps to preserve their cultural identities.”

Under the class action lawsuit, payments to former youth in care range from $25,000 to $250,000.

“We have been working with affected youth and their representatives to ensure that they receive fair compensation in a way that doesn’t cause further trauma,” a ministry spokesperson said in an email.

The ministry also said that when the matter first came to light, it took immediate and concrete steps to protect and strengthen financial controls.

“We are committed to protecting children and youth in our province, and working to ensure their well-being,” said spokesperson Ashley Williams. “We offer our heartfelt apologies to all the young people who have been affected.”

Saunders was fired from the ministry in May 2018.

He is still awaiting his sentence from the judge.

— with files from Kathy Michaels and Darrian Matassa-Fung

Comments