The Alberta Medical Association is concerned about “deeply troubling” survey results showing a worsening of the mental health of children in the province.

“It was not a surprise because we’ve been seeing it clinically. The mental health concerns in all ages has really escalated throughout the pandemic,” Dr. Vesta Michelle Warren, AMA president, said.

“What was surprising was the severity, particularly in the teen population.”

According to a survey from the AMA conducted via albertapatients.ca, 77 per cent of parents reported the mental health of their child aged 15 and older is “worse” compared to before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Four-in-ten parents of older teens said their child’s mental health is “much worse” today.

“The study itself showed, the older the child was, the more likely they were to have had a negative impact on their mental health throughout the course of the pandemic,” Warren said.

For children between the ages of six and 14, 70 per cent of parents reported their child’s mental health is “worse” than before the pandemic. One half of parents with kids under the age of six also reported some mental health declines in their children.

Warren said during the pandemic, children lost access to natural outlets for stress and anxiety — such as sports and after-school activities, and instead spent more time on screens.

“When I speak to some of my pediatrician friends, they really see the internet, social media and this ubiquitous use of computers — whether it be a cell phone or iPad or computer itself — as really being one of the big problems with respect to the mental health issues that we’re seeing right now,” Warren said.

Access to mental health resources

Warren said the pandemic has made the process of accessing mental health resources for children more difficult.

“It’s gotten worse for sure to try and link people in it and especially to get them linked in a timely fashion,” she said. “It may be months before they’re actually seen and sometimes that’s too long.”

Get weekly health news

“I’ve heard of cases where we’ve started that referral process to see somebody and the child becomes an adult before they’re seen by the pediatric psychiatrist — and now the wait starts all over again.”

As for solutions, Warren said Alberta needs to recruit and retain child psychiatrists, consider out-of-the-box ways to treat children, and improve funding.

“When it comes to kids, costs should not be an issue.”

“I think we need to be spending the money on our kids now, to make sure they’re as healthy as they can be so that when they’re adults, they can lead the way and be there for their own kids down the road.”

She said Alberta should consider offering virtual group therapy sessions as a potential solution to increase the access to specialists.

Dr. Bonnie Islam, an Edmonton pediatrician, said the survey results are troubling — but not surprising. She said they represent what doctors are seeing in their clinics.

“We’re seeing parents that are at their wits’ end and asking for help and not being able to access services,” Islam said.

“Or when we do direct them to services that we usually do, they’re being told because of the long wait lists, your child’s needs are not severe enough.”

What does Alberta Health Services have to say?

Mark Snaterse, executive director of addiction and mental health with Alberta Health Services in Edmonton, said the AMA survey “absolutely reflects” what the health authority has been seeing as well.

Snaterse said AHS is recording a 35 per cent increase in new kids being referred for mental health services.

In 2019-2020, AHS would average about 300 new referrals per month — now, it’s about 450.

“We do everything we can to try and triage and get kids that are most at-risk in as quickly as possible,” Snaterse said.

“Wait times — we always want to improve on those. Unfortunately, the wait time can be far too long.”

Snaterse’s recommendation for parents looking for mental health support for their children is to ask for help where families already have connections, such as a family doctor, pediatrician, school counselor or a parent’s employer.

If families have no connections, he recommends calling the provincial mental health hotline, which is 1-877-303-2642 (Toll free).

Alberta government response

On Tuesday, the Alberta Government posted its Alberta Child and Youth Well-being Action Plan online, addressing the 10 recommendations made by the Child and Youth Well-being Report.

The plan includes expanding of mental health and behavioural supports in schools.

Steve Buick, the health minister’s press secretary, said in a statement the government is aware of the impact the pandemic has had on children’s mental health.

“Given the strain on kids from school closures and other restrictions, unfortunately we’re seeing a big increase in mental health concerns among kids, and a big increase in demands on kids’ mental health professionals of all kinds,” Buick said.

“We’ve tried to learn from that and reduce the burden of restrictions on kids as we’ve moved through the pandemic, because it’s clear that the burden on kids is so much heavier than on adults (and the risk to them from COVID is less, although it can still be serious). We resisted closing schools in the last wave and we firmly believe that was the right choice.”

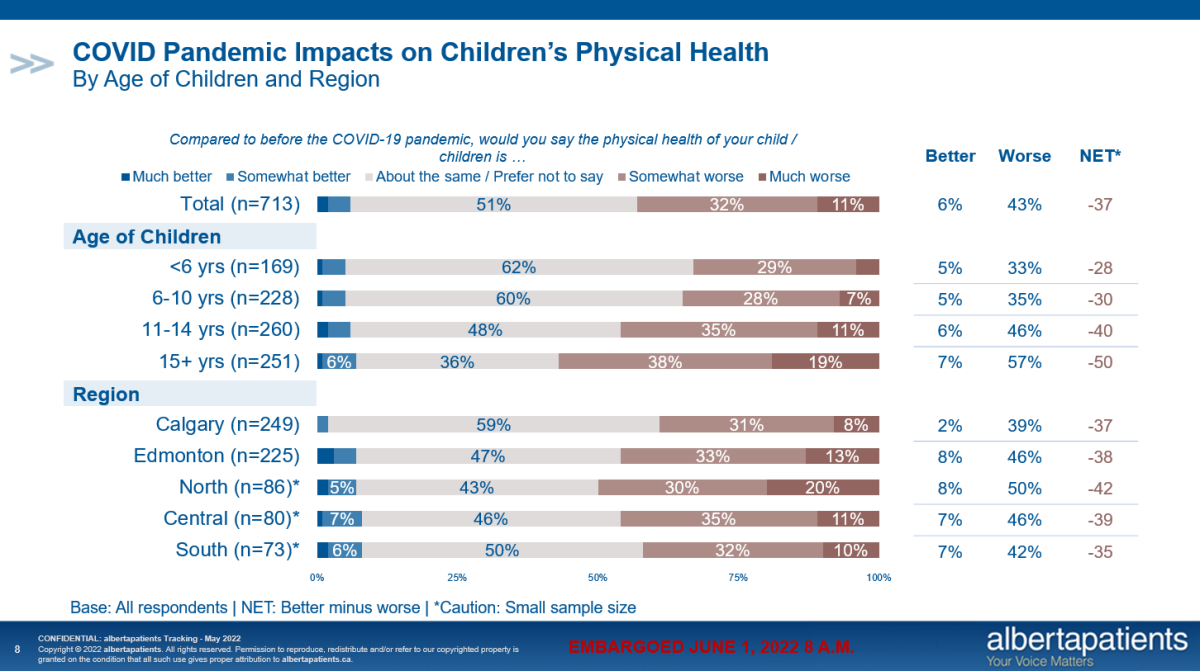

The online survey fielded by the albertapatients.ca online research panel was conducted from May 4 to 14, with a sample size (have children at home) of n=713.

The AMA said a probability sample size would yield a margin of error of +/- 3.7 percentage points 19 times out of 20 at a 95 per cent confidence interval.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.