Canadians reading the news across the country right now are seeing the term “record” in stories on gasoline prices more often.

It’s a fact that is impacting every motorist across the country — the price for regular gasoline is at highs never seen before.

They’ve been increasing since late last year, Statistics Canada data shows, and a significant drop might not come for a while, said Patrick De Haan, head of petroleum analysis at GasBuddy.com.

“We are at all-time record highs across Canada in many areas,” he told Global News.

“Unfortunately, we continue to set new records almost every day as we make the transition to summer gasoline across Canada, and as we see oil prices continue to go up as a result of the Russian invasion of Ukraine and escalations in that situation.”

At this time last year, the average price in Canada for regular fuel was $1.31 a litre, Statistics Canada data shows. The average price of regular gas in Canada on Friday was $1.86 a litre, De Haan said.

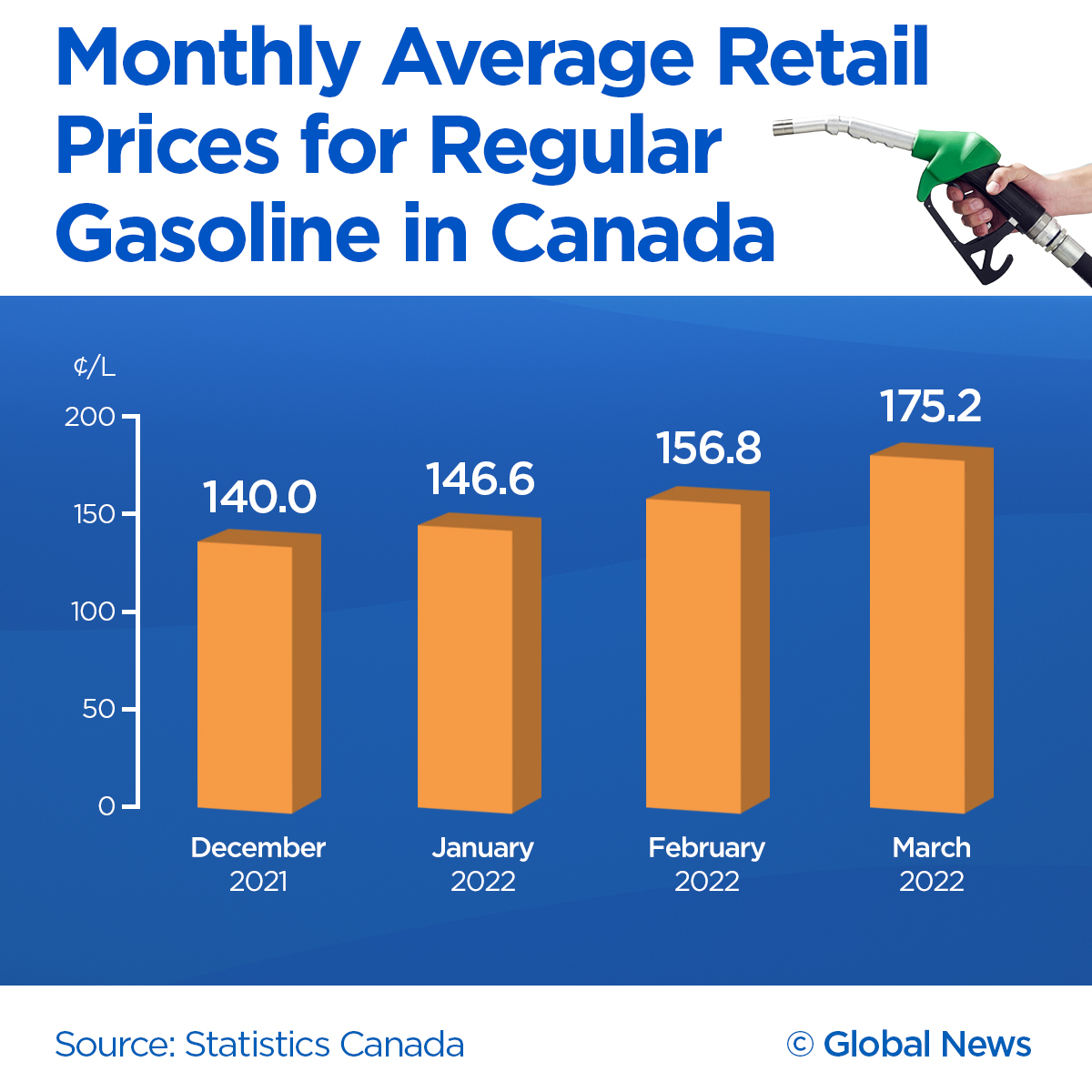

Gas prices began to increase in Canada starting in December, when the average price for regular fuel was $1.40 a litre, according to Statistics Canada. In March, one month into Russia’s Ukraine war, the average price for regular gas was $1.75 a litre, up from $1.56 a litre in February. Average prices for April are not yet available.

Get breaking National news

Of course, the price for regular gas varies across the country. In British Columbia on Friday, the average price of regular gas was $2.02 per litre, Gasbuddy.com said. On Wednesday in Metro Vancouver, the price at the pumps read $2.11 a litre.

Newfoundland saw the highest prices at the pumps on Friday with the average being $2.06 a litre, Gasbuddy.com said. Alberta had the cheapest fuel at $1.60 per litre.

The COVID-19 pandemic changed driving habits when lockdowns forced residents to stay home and commute less, De Haan said. Oil producers cut production early on in the pandemic to meet low demand, but have had trouble keeping up as demand increased, he added.

That, on top of Russia’s war on Ukraine and the West’s economic response to it, has driven gas prices sky high, De Haan said.

“The challenge is that there’s been a growing imbalance between supply and demand, and that imbalance widened even more substantially after Russia’s war in Ukraine,” he said.

Russia, one of the world’s biggest oil producers, launched a military invasion of Ukraine on Feb. 24 that has rocked global economies.

Part of that is due to several sanctions levied by the West against the Russian economy, a move the allies hope will choke Moscow’s ability to fund its war effort.

On Feb. 28, Canada said it would block all imports of Russian oil despite not having purchased any since 2019, the government said.

On March 8, the United States banned all imports of Russia’s oil, but announced it would help release millions of barrels of oil from strategic reserves. The move was aimed to help lower the prices at the pumps, they said, but also help nations dependent on Russian oil to move away from their products.

Many of those nations are in the European Union, which until now has resisted introducing a ban on Russian oil. But with the war showing no signs of slowing down, and the brutality reportedly getting worse, the EU proposed a ban on Russian oil this week with incentives for member nations who can’t dump the product straight away.

“As long as those sanctions are in place that can impair Russia’s ability to sell oil, we’re going to have an imbalance in supply and demand in the global market,” De Haan said.

“I really don’t think we’re going to see improvement for quite some time, and I would tie it to a resolution between Russia and Ukraine.”

With oil being a global commodity, Canada is at the mercy of world events, said Ian Jack, vice president of public affairs at CAA.

Oil producers are also set to switch to summer blends of gas, which costs more to produce than the winter blends currently on the market, Jack said.

For immediate relief, governments can likely reduce taxes on gas products, but the savings may not be much, given prices are so high, he added.

“There’s no way governments can magically return the price to where it was,” Jack told Global News.

“If you think about the price of gas being well under a dollar a litre … the government take (on taxes) could be reduced, could help a bit, but you’re not you’re not going to return those prices.”

Cutting taxes could also backfire and lead to more demand, De Haan said.

“Really, the only improvement is going to touch on one of those, either increasing supply, which appears impossible given the constraints of refineries and given the global market for oil, or reduce demand or reduce taxes,” he said.

“Reducing demand is very difficult. … You can’t ask people to stay home, so there’s not a whole lot government can do to decrease demand other than to allow the high prices to start causing demand destruction. So that and like I said, they can alleviate taxes temporarily, but that could make the problem worse as well by driving demand up.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.