March 31st marks Indigenous Languages Day, an occasion celebrating Indigenous language revitalization while signifying the urgency to preserve something culturally critical.

“I think the struggle that we’re dealing with right now is we’re fighting against a clock,” says Melanie Kennedy, executive director of Indigenous Languages of Manitoba.

“How we battle through that is just by ensuring that we are following the guidance of our elders and documenting that language before our speakers are no longer here to share that with us.”

Despite the help of existing resources, Kennedy says many Indigenous languages and dialects are in a critical state.

“The focus really remains today on the critical need to develop language speakers, proficient language speakers.”

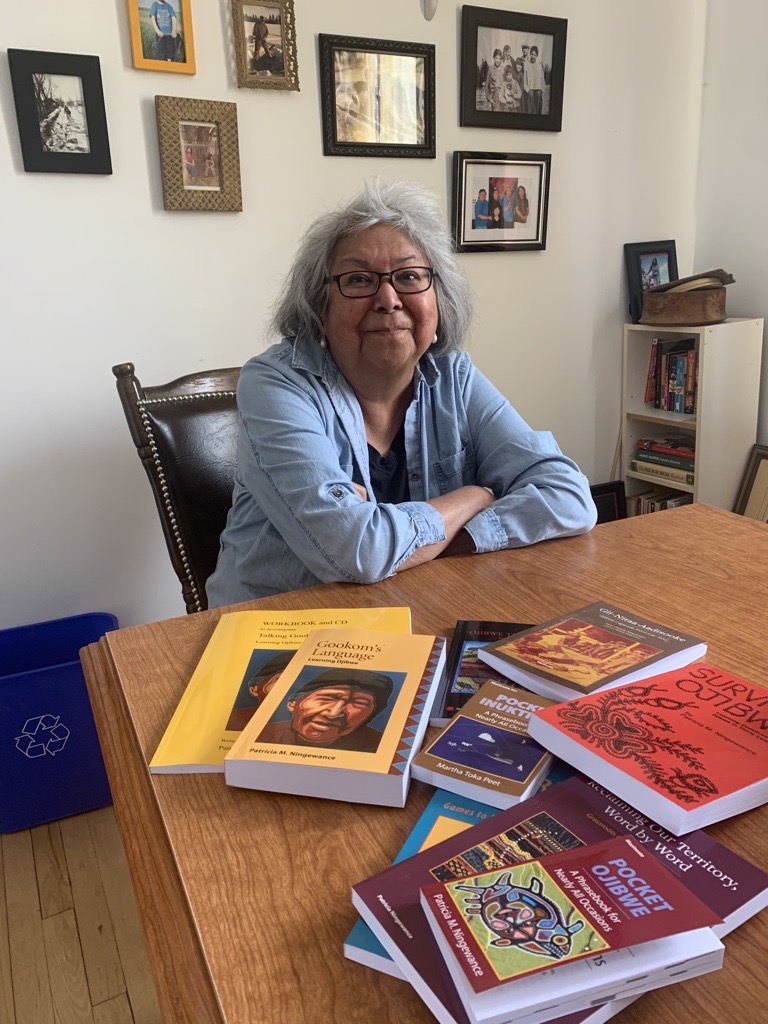

Author Patricia Ningewance works to make sure Ojibway lives on. For over four decades, she has taught classes and written 14 books.

In her book titled Gookom’s Language an image of Ningewance’s grandmother is depicted on the cover, to honour what inspired her work.

“It really affected me very, very positively, very profoundly,” Ningewance says. “That’s probably why I was so proud of my language because of her and my parents.”

But the bigger goal is fighting to win back what was stolen by colonizers, she said.

Get breaking National news

“(For a) long time I denied it, but I can’t deny it anymore. They succeeded. We have people my age that don’t speak it anymore,” she says. “(There are) people my age who speak it, but don’t pass it on in the family anymore because it gets stuck here. There’s a block here.”

Dakota Elder Wanbdi Wakita from the Sioux Valley Dakota Nation says he remembers when his sisters were forced to go to a residential school.

“I grew up in a very safe and happy home. We had a small farm and everything was good. My mom and dad, my grandpa and my brothers and sisters, we used to talk at night when I finished the day,” he says. “You know, my two older sisters were forced to go to residential school and then our talks stopped because the family circle was broken.”

Eventually Wakita was put in a residential school himself, and has since become protective of his language, and speaks it every day.

“I’m not Canadian. I’m not Manitoban. I’m not a Winnipegger. I’m Dakota.”

Ningewance says she wants to see more representation for her language in media, more camps for kids in Indigenous languages, tourism experiences where true immersion of the culture can be achieved.

“If you get swallowed up by English, and English is everywhere … at what point do you start identifying with the culture, the worldview of that language, when you stop thinking of yourself as an Anishinaabe?”

Kennedy says there are a number of ways people can help support Indigenous language revitalization.

“If you want to be involved, there are many events, especially now opening up that would be more than happy to have volunteers to come and help out,” she says. “It’s a great way to show your support and become involved in that work.”

— with files from Lauren Mcnabb

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.