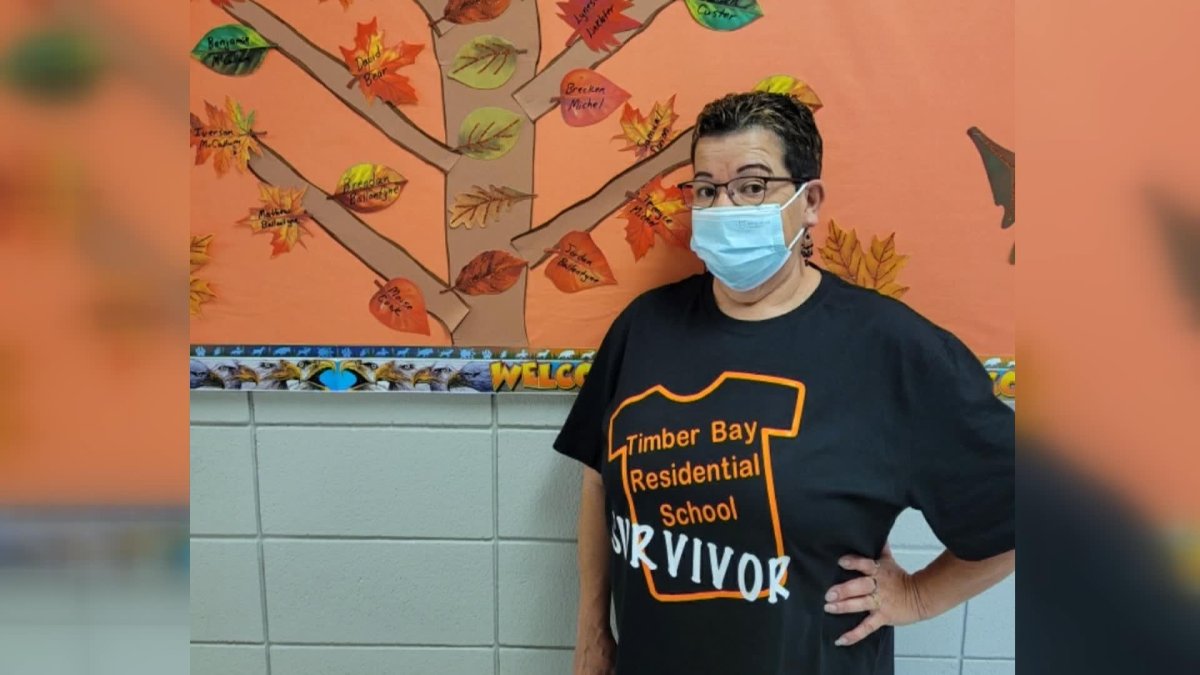

Yvonne Mirasty was nine years old when she was taken.

“When my mom got home from work, we were gone.”

Along with her siblings, Mirasty was placed in the Timber Bay Children’s Home, which the Northern Canada Evangelical Mission and later the Brethren in Christ Church ran between 1952 to 1994.

The home in the northern Saskatchewan hamlet of Timber Bay near Lac La Ronge, was used for children who attended school elsewhere. Most of them were First Nations or Metis.

Survivors have described it as a residential school for Indigenous children, even though the federal and provincial governments have not designated it as such.

“It wasn’t happy memories at all. I don’t remember anything good out of that place,” says Mirasty, 60, a teacher in Pelican Narrows, Sask.

She says children at the Timber Bay home were treated like prisoners, forced to do hard labour, and would get punished if they didn’t memorize Bible passages.

Many times, Mirasty says, she went to sleep hungry and had to take cold baths.

“I used to cry myself to sleep. I don’t know if I thought my parents were dead. I used to sing all the time to put myself to sleep.”

Mirasty says she was abused during the two years she spent at the home. She says a supervisor took her to his office, where he sexually assaulted her.

“He’d say, ‘Kiss daddy, kiss daddy.’ I can still hear him to this day.”

Mirasty faced the same horrors as many other Indigenous children taken from their homes and forced into government-funded institutions, but she’s not entitled to the same compensation from the Canadian government. Nor the recognition.

“They say every child matters, but what about Timber Bay? All I want is to be recognized, and hear them say these kids suffered, too.”

The federal and Saskatchewan governments have not recognized the Timber Bay home as a residential school, because it doesn’t fit the legal definition under the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement.

It’s not the only one.

Federal government data shows nearly 9,500 people asked for 1,531 institutions to be added to the agreement between 2007 and 2019.

Of those, Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada have recognized seven. The courts have identified another three.

The government’s website says in 2019 there were 140 eligible residential schools as part of the agreement.

The Timber Bay home received federal government funding and other services, but the courts denied its designation as a residential school.

The Saskatchewan Court of Appeal ruled that children were not placed in the home for the purpose of education and the federal government wasn’t responsible for the residence and care of the children. The Supreme Court of Canada dismissed an appeal of that decision.

In a statement, the office of Crown-Indigenous Relations Minister Marc Miller said it is committed to working with survivors and families to address historical wrongs. It said there are also outstanding claims regarding Indigenous children in educational and care homes not operated by the federal government.

“Addressing historical claims related to harms committed against Indigenous children is a crucial step toward strengthening our relationships with Indigenous Peoples,” the statement said.

Litigation against the Saskatchewan government is before the courts, so the province declined to comment.

Survivors of Timber Bay and their descendants say they will keep fighting.

Dwight Ballantyne, who is from the Montreal Lake Cree Nation, had family who attended the school. He says he feels like he has been silenced by the federal and provincial governments.

“There’s a lot of stories that need to be heard. It’s part of who we are as Indigenous people. Growing up, I felt like I was supposed to be quiet and not tell my story,” he says.

“A lot of survivors get their stories swept under the rug.”

Ballantyne is petitioning the province to have Timber Bay acknowledged as a residential school.

“I want to make enough noise to hopefully get Timber Bay recognized … in hopes that it’ll open the door for the other schools that are not recognized.”

In February, the Timber Bay home was discussed at a meeting between Miller, Indigenous leaders and the Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations, which represents 74 First Nations in Saskatchewan.

“There were many horrific experiences within those schools, within those grounds. The children suffered the same abuses, and in some cases even death,” said federation Chief Bobby Cameron.

“It should not be shuffled off to the side, forgotten or ignored. Those descendants deserve to be compensated, and for those that lost their lives in Timber Bay to be recognized properly.”

Saskatchewan RCMP continue to investigate circumstances surrounding a death that may have happened at the Timber Bay home in 1974. Mounties announced the investigation last year.

In a recent statement, they said they can’t provide specific details but have been taking statements, following up on tips and reviewing records from the home. Officers have also visited the site.

“What we went through mentally, physically, sexually — I don’t know how we survived,” says Mirasty.

“Don’t forget about us.”

The Indian Residential Schools Resolution Health Support Program has a hotline to help residential school survivors and their relatives suffering trauma invoked by the recall of past abuse. The number is 1-866-925-4419.

Comments