As Russian troops descended on Ukraine, the internet lit up with footage said to be from the region — destroyed buildings, planes lighting up the night sky, and air raid sirens ringing in the background of live streams.

There’s just one problem: not all of this footage was real.

Some videos amassed hundreds of thousands of views on social media, only to be revealed as video game graphics, old combat footage, or even proven to show another country altogether.

“It’s very difficult at times to figure out whether something is factual,” said Mary Blankenship, a University of Nevada researcher who looks at how misinformation spreads through Twitter.

“A part of what makes this so difficult is because the situation is changing, literally by the minute.”

Here are the tools experts say you should use to wade through the waves of misinformation — and disinformation — that are coming from the region.

What does misinformation look like?

Misinformation and disinformation are not the same thing. Misinformation is untrue information shared by someone who mistakenly believes it to be factual. Disinformation, however, is deliberately spread.

In the case of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the world is seeing a lot of both.

For example, a Belarusian news outlet shared an image they described as showing a Ukrainian pilot shooting down a Russian attack aircraft. The video was viewed over a million times in less than a week.

However, it was later confirmed that the video was actually a graphic from the video game Arma 3 — and had nothing to do with the ongoing conflict in Ukraine.

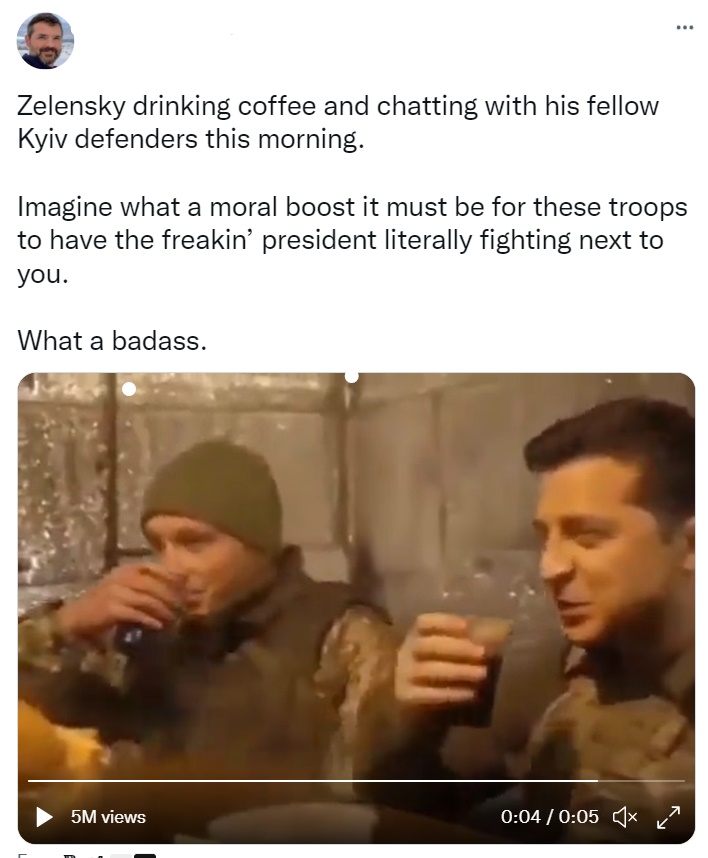

Another video, which was later corrected, suggested Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy had joined troops for a coffee following the Russian invasion.

However, while the footage was indeed real, it was misleading — the video was older, and from just before Russia had invaded.

Both of these posts may contribute to what one media literacy expert described as the goal of disinformation.

“The purpose of disinformation (is) generally not to convince us of a particular view, but to make us doubt that anything is true. It’s to paralyze us,” said Matthew Johnson, director of education for MediaSmarts, a Canadian non-profit dedicated to digital media literacy.

Get breaking National news

“That’s one of the big differences between disinformation and misinformation. Misinformation is something that is shared by someone who believes that it is true, and generally they want you to believe it. But the purpose of disinformation really is to sow doubt and to paralyze.”

How do you know if something is fake?

There are a number of tools Canadians can use to verify the news they see.

One of the early indicators that suggests something could be misinformation, disinformation or propaganda is if it makes you feel a strong emotion, according to Blankenship.

Misinformation and disinformation have “the greatest chance of being perpetuated” when they instill “feelings of fear and anger against another group.”

“That works both ways. It works for the Ukrainian side, and it works to the Russian side, with propaganda disinformation.”

When videos are emotional, Blankenship said, people are more likely to interact with them — including liking them, and reposting them. This often prompts algorithms to push them out to a broader audience.

So let’s say you see an emotional video, and you want to like and share it. Interacting with it will amplify it, so before you do that, you should make sure it’s real.

One excellent way to do that is relatively simple: Google it, says Jane Lytvynenko, a senior research fellow with Harvard University’s Technology and Social Change Project.

“Google what you’re seeing with some key terms, with the word ‘fact check,'” she said.

“Fact-checkers are working overtime to try to figure out what’s real and what’s not.”

Johnson echoed this suggestion.

“It’s good to have a toolbox of fact checkers that you’re familiar with,” he said.

MediaSmarts has developed a custom fact-checker search engine, too, which you can use to Google something you saw. All the results, Johnson explained, will be from verified fact-checkers.

After searching your story on Google, you want to check your source. Blankenship explained that you may want to run the account sharing the information through a tool that will tell you the likelihood that it’s a bot.

Johnson also suggested clicking through until you know where the information originated from. If you see a video on TikTok with air raid sirens in the background, make sure it’s original audio, not someone imposing the real sound over fake footage.

If you see a post shared on Facebook, determine the original author and consider their track record.

If you’re happy with the source and there’s no evidence the footage or story has been debunked, you can also look for a second source sharing the same information.

“What you’re looking for here is a consensus. So if you’ve only got one source reporting it, unless it’s something that just happened, you want to be skeptical,” Johnson said.

Lytvynenko added that you can speed up the process by making sure you follow strong sources in the first place — especially people who are on the ground in Ukraine.

“Russia has a vested interest in spreading mis- and disinformation, as it has been for the last decade or so, and so that is why the following of reliable sources on the ground is the best advice that we can give in this moment,” Lytvynenko said.

So you found fake news -- now what?

If you’ve investigated the source of the footage or article you had planned to share and find out it’s fake, the next steps you take are important — because you don’t want to amplify the fake claims.

“The best thing to do is not to interact with it at all. So don’t comment, don’t re-post it,” Blankenship said.

“The algorithms on social media, they don’t know whether your agree or disagree with the content. They just know that the content is getting interactions, so they’re going to perpetuate that. So the best thing to do is leave it alone.”

However, that doesn’t mean you can’t call attention to the falsehood that’s spreading. The first thing you should do, according to Lytvynenko, is to report the post to social media companies.

If you decide you want to let the world know about the false information, the best way to do it is through screenshots and a fresh post, according to Lytvynenko.

“Screenshot it and then share it, rather than amplifying the account and the false information itself, which can then travel further,” she said.

If you already shared the post itself, though, that’s not the end of the world either. Just delete the tweet, Lytvynenko said, and post a screenshot showing your error with some kind of stamp on it so it can’t be misused. Then explain why you deleted it, she said.

Taking these precautions online is more important than ever, according to both Lytvynenko and Blankenship. Both have family in Ukraine, who run the risk of being directly impacted by the real effects of misinformation campaigns.

“Domestically within Ukraine, the purpose of mis- and disinformation, particularly disinformation, is to attempt to sow panic, to attempt to undermine Ukrainian army movements and in some cases increase civilian casualties,” Lytvynenko said.

That’s why Ukraine needs the international community to do its due diligence when it comes to fact checking claims, added Blankenship.

“A lot of Ukrainians already think that this sort of next stage of the conflict, a big portion (of) it is information warfare,” Blankenship said, pointing to the fact that Russia attacked the main TV tower in the heart of Kyiv on Tuesday.

“They’re trying to really isolate people from media updates to really break up that resistance. So right now, showing solidarity and making sure the information that you perpetuate and share is correct is of utmost importance.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.