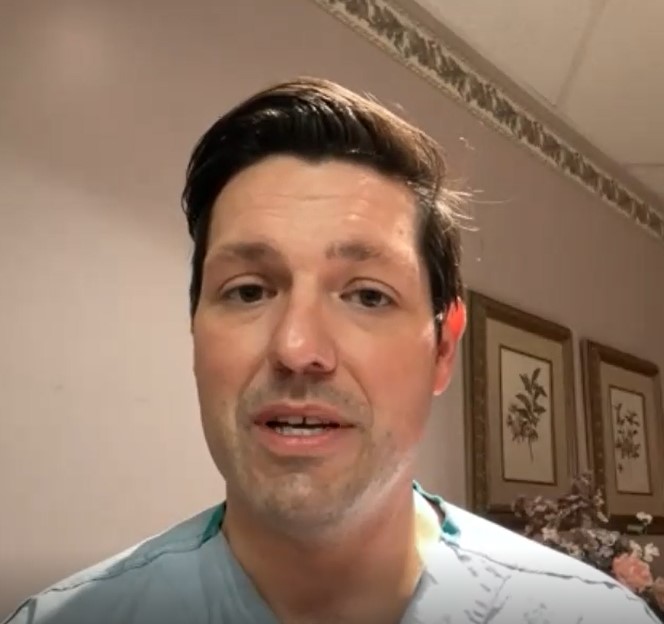

Dr. Kevin Wasko has seen patients die from COVID-19, worked seemingly nonstop for two years to help plan and implement the province’s response to the pandemic in rural areas, and seen his efforts and those of his colleagues attacked by people who no longer trust science or the intentions of those who tirelessly strive to help others.

And he’s had enough. He’s leaving Saskatchewan.

Wasko is an emergency room doctor and family physician in Swift Current. He’s also part of the Saskatchewan Health Authority executive team tasked with planning how to deliver health care to rural parts of the province.

On Tuesday he announced on Twitter he has accepted a new position with the Trillium Health Partners Hospital in Mississauga, Ont.

The move from a rural area to an urban setting was deliberate, he said.

“It’s been a very trying time,” he told Global News in an interview.

“And at this point, as I see (the province) coming out of this, I think it’s an opportunity for me to be able to step back for a while and focus on something different, which would be my clinical practice.”

He said the burden of being an ER doctor treating patients combined with the weight of leadership was substantial.

Seeing so many patients die, especially during the fourth wave, “is traumatic for health-care workers, to have your patients pass on when they’re in your care repeatedly one after another,” he said.

“And that’s traumatic for leaders to know that the people they’re wanting to lead, the people that they need to be there for, are experiencing that.”

But events outside of the health-care system also added to the strain. Wasko said he struggled seeing the anti-vaccine rhetoric aimed at health-care workers.

Get breaking National news

“We do care about people a lot,” he said.

“I want the best for the people that I care for as a physician and that I want to lead as a leader in our system. So to hear those comments, to see the freedom convoy travelling to Ottawa and saying that this is tyranny, is extremely disheartening.”

Wasko said the anti-intellectual, populist backlash against health orders is stronger in rural areas.

And it’s tough because of his personal connections.

He’s from Eastend, Sask., about 140 kilometres southwest of Swift Current. According to 2016 census data, just 503 people live there.

“I understand how people think in rural Saskatchewan because they are the people I grew up with and who I know and who I care about,” he said.

And he said having a provincial government that has contradicted medical advice, in announcements and letters from political leaders or in policies, can dishearten health-care workers even more and further erode the trust between health-care workers and the general public.

“We make recommendations based on the best information that we know, and we recommend what should happen,” Wasko said.

He said government leaders act on what they believe the province’s residents want, but ignoring scientific advice increases the disconnect between what medical professionals and scientists know is the right course of action and what the public wants that course of action to be.

The president of the Saskatchewan Union of Nurses (SUN), Tracy Zambory, said that division exists across the province.

“The impact on registered nurses and, in fact, the entire health-care team has been devastating. It has been nothing like anyone could even imagine,” she said, speaking from Stoughton, Sask.

She said politics is disrupting patients’ interactions with the health-care system and that the messaging from Premier Scott Moe and the Saskatchewan government is making it more difficult to deliver care.

She said the government should follow scientific advice and keep public health orders designed to stop COVID-19 from spreading in place.

“We are confusing what needs to be happening here with … ‘personal freedoms,’” she said.

“This isn’t about personal freedoms. This is about keeping people in this province safe.”

She said many nurses were experiencing burnout and feeling unsupported and many are also considering leaving the province or profession.

The provincial government has announced plans to bolster the ranks of health-care workers, like hiring between 150 and 300 additional nurses from the Philippines.

Zambory said that process is very slow and that nurses must have certain qualifications to practise in Saskatchewan that are not always easy to meet.

On top of that, she said the number of combined vacant shifts in Saskatoon hospitals over some weekends can reach as high as 200.

Wasko’s announcement prompted an outpouring of thanks from colleagues in Saskatchewan and across the country for his guidance and service.

“You have been an incredible leader in difficult times,” Dr. Katherine Smart, the president of the Canadian Medical Association, tweeted.

“This is a huge loss for (Saskatchewan),” family physician Dr. Adam Ogieglo replied.

“Their gain is (Saskatchewan’s) loss. Sorry to see you go, friend, but I completely understand,” emergency medicine and trauma physician Dr. Brent Thoma added.

Wasko said he’s spoken to some of his fellow doctors who are also considering leaving.

“I think we are all doing a bit of reflection and soul searching at this juncture to really see what it is that we want out of our careers. What do we want for ourselves and our families?” he said.

Global News asked the provincial government about health-care worker retention. No one responded by deadline.

Comments