The chair of a Hamilton group monitoring the city’s air quality says generally there have been improvements amid the COVID-19 pandemic despite minute challenges with a potentially toxic gas and smog.

The annual report from Clean Air Hamilton says residents didn’t benefit from a big drop in air pollution in 2020, despite lockdowns.

Bruce Newbold, the group’s chair, however, told the city’s board of health that an overall trend of improvement that began in the 1990s has continued.

“The news continues to be good within the city in terms of the reduction in criteria air pollutants,” Newbold told councillors.

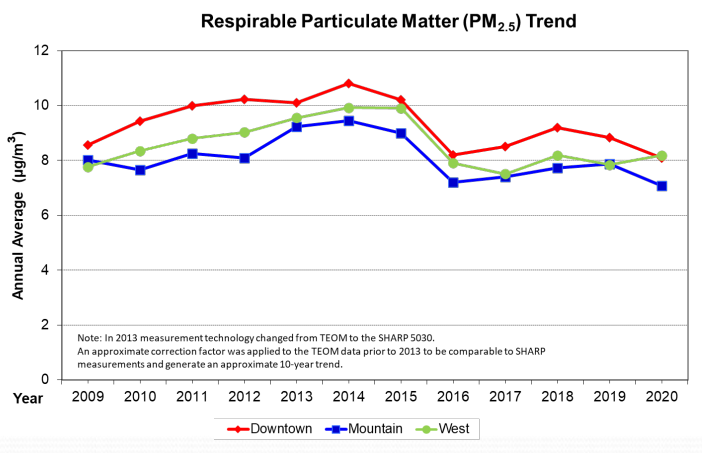

“Although we know that there are variations in air quality across the city, what we see in the west end of the city … differs from elsewhere within the city.”

The study revealed dust levels fell slightly in the city core and levels of nitrogen dioxide remained stable, while sulfur dioxide and particulate matter edged higher in 2020.

Emissions at municipal and industrial sites have been declining since 1996 with suspended particulate matter below desired annual concentrations set by the Ontario’s Ministry of the Environment guidelines.

Inhalable particulate material, primarily derived from vehicle exhaust, road dust and industrial stacks, have also decreased over the last two decades, a change that’s suspected to be a reflection of better vehicle performance and street sweeping practices in the city.

Newbold says the counter to that, though, is an increasing number of trucks and heavy vehicles on city roads.

“Part of that particulate matter is associated with braking or idling of vehicles, so we know that that’s a place and we would like to see improvements … through sort of provincial piece and legislation associated with the trucking industry,” Newbold said.

Get daily National news

Fine particulate matter — an air pollutant that is a concern for people’s health when levels are high — has been trending upward particularly in West Hamilton according to Newbold, who says sources outside of the city contribute to overall numbers.

“It’s transportable through our air systems, and so we could be seeing particulate matter or PM2.5 coming to us from, say, the Ohio Valley, for instance,” Newbold said.

Ground level ozone — a major component of smog that comes from photochemical reactions in the presence of the sunlight — had a marked increase in 2020 despite being variable over the last 20 years.

In 2020, the city recorded more hourly readings above 50 parts per billion (ppb), which the monitor considers high.

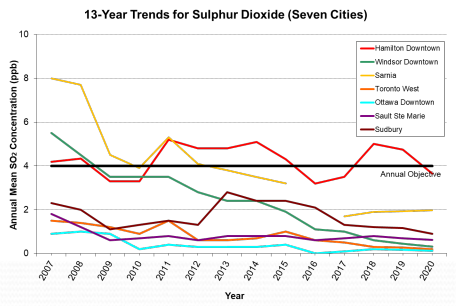

During the last 30 years, Hamilton’s trend in ozone levels has been comparable to a number of other nearby communities, but concentrations of sulphur dioxide have not.

A byproduct of smoke from matches, coal and some fuels, the chemical compound is mildly toxic and hazardous in high concentrations if inhaled.

In the last 13 years, the city has exceeded its objective of keeping levels at 4 ppb, much higher than a number of other neighbouring Ontario municipalities.

“It probably reflects the mix of industry that we have within the city and the location of industry within the city compared to some of these other locations,” Newbold explained.

The study’s message is generally good overall, but suggests making efforts in reducing sulphur dioxide and investing in more tools for more accurate testing.

“We’ll continue to expand air quality monitoring by looking at projects within the community, along with partner organizations and academics, to better understand air pollution concentrations at the neighbourhood level,” Newbold told councillors.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.