The U.S. has ordered an arms embargo on Cambodia, citing deepening Chinese military influence, corruption and human rights abuses by the government and armed forces in the Southeast Asian country.

The added restrictions on defense-related goods and services, issued by the State and Commerce departments, are due to be published and take effect Thursday.

A notice in the Federal Register said developments in Cambodia were “contrary to U.S. national security and foreign policy interests.”

The aim of the embargo is to ensure that defense-related items are not available to Cambodia’s military and military intelligence services without advance review by the U.S. government, it said.

The latest restrictions follow the Treasury Department’s ordering in November of sanctions against two senior Cambodian military officials for corruption and come amid increasing concern about Beijing’s sway.

At the time, the U.S. government issued an advisory cautioning American businesses about potential exposure to entities Cambodia and its military that “engage in human rights abuses, corruption and other destabilizing conduct.”

Cambodia branded those sanctions as “politically motivated” and said it would not discuss them with Washington.

The U.S. has similar controls on exports of items that might be diverted to “military end users” in Myanmar, China, Russia and Venezuela.

U.S. exports to Cambodia in 2019 totaled $5.6 billion. The amount of military-related U.S. exports to Cambodia was not immediately available. The U.S. is the largest export market for Cambodia, a major garments manufacturing hub, but three-quarters of Cambodia’s imports are from China and other countries in Asia.

Get breaking National news

The U.S. halted military assistance to Cambodia following a 1997 coup in which the country’s leader, Hun Sen, grabbed full power after ousting his co-premier, Prince Norodom Ranariddh. Hun Sen remains prime minister. In August 2005, President George W. Bush waved the ban, citing Phnom Penh’s agreement to exempt Americans in Cambodia from prosecution by the Netherlands-based International Criminal Court.

Since direct military ties between the two countries were restored in 2006, the U.S. has pledged millions in military aid to Cambodia, initially to help improve its border security and peacekeeping operations.

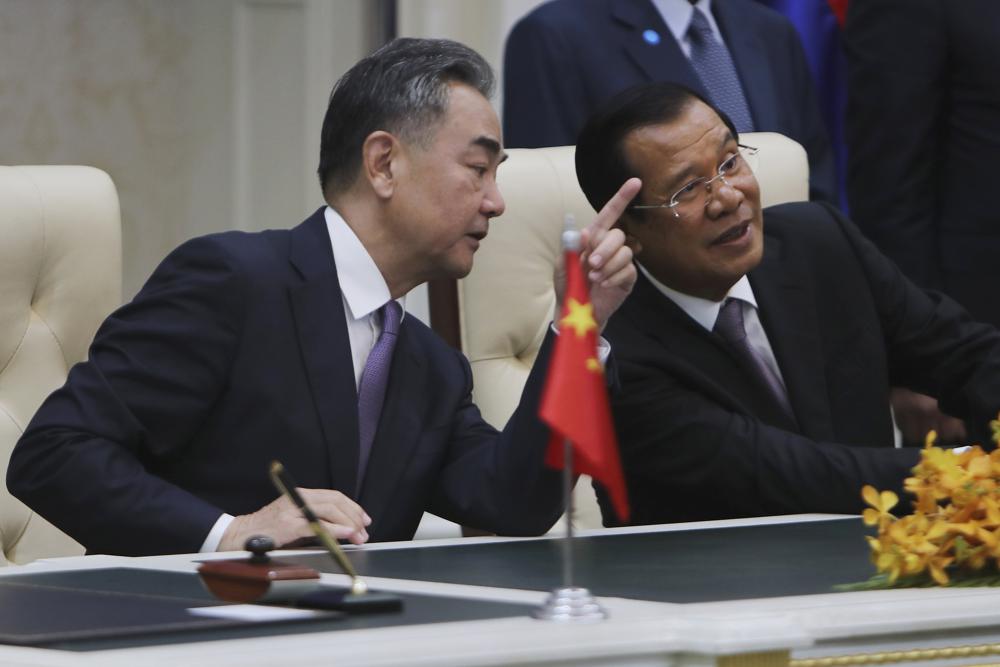

China is Cambodia’s biggest investor and closest political partner. It was the chief backer of the murderous regime of Pol Pot in the 1970s and has long maintained strong relations with Hun Sen, who has ruled for more than 30 years and grown increasingly repressive.

- Trump family wants to own trademark if airports use president’s name

- Canada can’t be ‘naive’ to China’s transnational repression threat: report

- What is the Jay Treaty cited in First Nations travel advisories to the U.S.?

- Zorro Ranch: New Mexico approves full investigation into former Epstein property

Beijing’s support allows Cambodia to disregard Western concerns about its poor record in human and political rights, and in turn Cambodia generally supports Beijing’s geopolitical positions on issues such as its territorial claims in the South China Sea.

The construction of new Chinese military facilities at Cambodia’s Ream Naval Base is a point of strong contention with Washington.

Ream faces the Gulf of Thailand, adjacent to the South China Sea, where China has aggressively asserted its claim to virtually the entire strategic waterway. The U.S. has refused to recognize China’s sweeping claims, and the Navy’s 7th Fleet routinely sails past Chinese-held islands in what it terms freedom of navigation operations.

In recent years, Hun Sen’s government has cracked down on the political opposition, shut media outlets and forced hundreds of Cambodian politicians, human rights activists and journalists into exile.

Human rights groups say the government has engaged in arbitrary arrests and other abuses and worked to portray peaceful dissent over corruption, land rights and other issues as attempts to overthrow the government.

Corruption is another major concern.

The Treasury Department sanctions targeted the director general of the defense ministry’s material and technical services department and a commander in the Royal Cambodian Navy.

In a statement, Treasury alleged that in 2020 and 2021, the two conspired with other Cambodian officials to inflate costs of a construction project at the Ream base and then planned to use the funds for their own benefit.

Washington has protested over work done at Ream, which officials said involved the demolition of two U.S. funded buildings without notification or explanation to the U.S.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.