Saskatchewan health minister Paul Merriman says he’s willing to review the case of a family denied coverage of over $800,000 in out-of-country medical fees.

Merriman told reporters that his office has communicated with the Finn family, originally from Saskatoon, before and said he’s willing to meet with them again.

“I’d be more than happy to sit down with them and have a discussion with any updates,” said Merriman, who didn’t rule out reimbursing the costs of the care — a request the Ministry of Health has so far denied.

“I’ll look at this with a fully open mind. I’m not going to go in and just reiterate speaking points.”

Joined by the Saskatchewan NDP before Question Period Monday, Kristin Finn told reporters how she and her husband have delayed retirement, moved to Kansas City from Saskatoon for work, and paid “just shy of $832,000” out-of-pocket for life-saving medical care for their young son, Conner.

But she maintains all of that could have been avoided had the province not denied reimbursing the out-of-country care.

“We’ve tried to follow the policies and procedures of the government, we’ve filed a complaint with the ombudsman which is now outstanding, we’ve filed a complaint with the human rights commission,” Finn said Monday.

“We’re still running into an issue where the government doesn’t want respond to our request for reimbursement.”

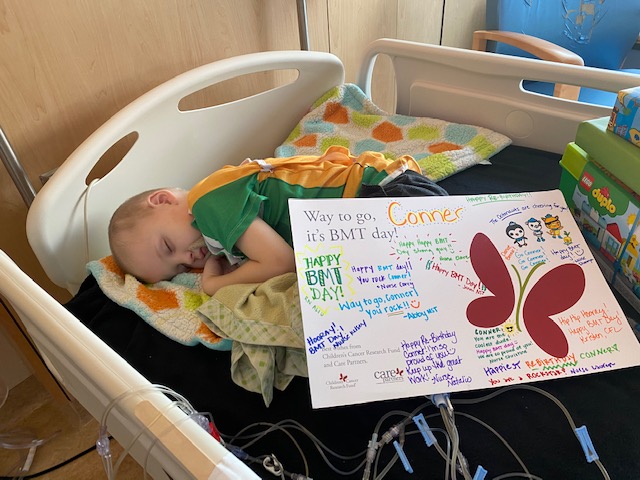

Conner has Adrenoleukodystrophy, a rare disease that causes inflammation in the brain, and received a stem cell transplant in 2020 at the University of Minnesota.

Finn said when he was first diagnosed last year, it was discovered via MRI that the disease was at an advanced stage and that the stem cell treatment was needed.

But she said the family was told Saskatchewan doesn’t offer pediatric stem cell transplants.

The family told Global News earlier this year that the province gave them the option of getting the transplant in Winnipeg or Toronto, but there was no clear timeline or an ALD specialist to treat Conner.

Get weekly health news

She said they took it upon themselves to do an “extensive cross-country search” and they determined that the University of Minnesota was the closest place Conner could most safely and quickly receive the treatment. The family traveled there amid the pandemic.

It was in Minnesota that a specialist, reviewing Conner’s MRI, told the family the treatment was needed immediately.

The Finn family decided to go ahead with the treatment even though coverage hadn’t been approved.

“We were left with the decision to sit around and wait and possibly fall out of the window for transplant and watch out son deteriorate and die, or liquidate our retirement savings to secure treatment for him and so we ended up doing that,” Finn explained.

Adrenoleukodystrophy stem cell transplants are unlike stem cell treatments for cancer, Finn explained, in that intense chemotherapy is needed to help repair the recipient to receive the donor cells.

She said delayed treatment, or improperly administered treatment, can actually increase inflammation in the brain, and bring the patient more quickly towards complications with vision, motor skills and more.

She said the family’s metabolic physician in Saskatchewan even wrote the Ministry of Health saying that being treated at the University of Minnesota would give Conner the best outcome possible.

That gave her all the more reason to seek care at the University, which she said treats around 70 per cent of the world’s adrenoleukodystrophy patients.

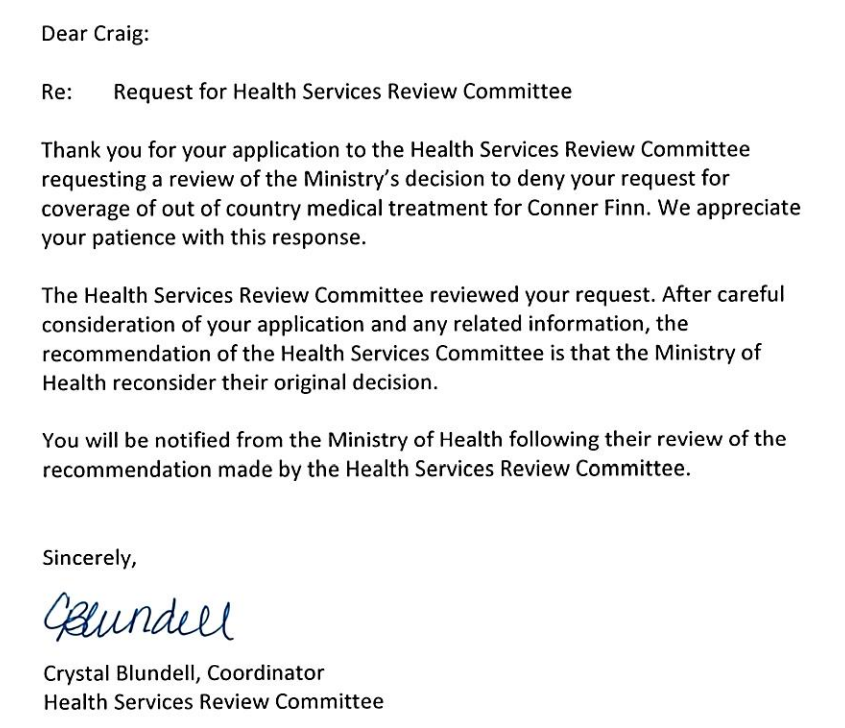

“Minnesota was the best place for him to be,” she said, explaining the family appealed to the Health Services Review Committee.

“The Committee decided Conner’s treatment should be covered due to the lack of expertise and the fact that they couldn’t provide any timeline for Conner’s transplant. But the government decided to go against that.”

Kristin Finn was joined Monday by Andrew McFadyen, who is the is executive director of the Isaac Foundation, an Ontario-based foundation focused on advocating for families coping with rare diseases.

McFadyen agreed that, particularly due to the urgency of Conner’s situation, the University of Minnesota was the only option to treat him in a timely enough manner.

“There aren’t ALD experts in Saskatchewan. There was nobody who could guide. Nobody who could help treat. Nobody to help ensure Conner was getting the best care he possibly could,” he said.

“There was no referrals made to places like Toronto or Calgary, and I can guarantee you that if those referrals were made those centres would have sent them on to Minnesota because it’s the right thing to do. And had a referral been made, that would have taken time. And it’s in that time I believe we would have lost Conner.”

Merriman said that when his office reviewed the reimbursement request, it wasn’t the dollar amount that influenced his decision.

“It was making sure we were following the proper process to get that surgery done in Canada.”

Merriman added that there are “stipulations in our legislation” that dictate care must be completed in Canada as “the first option” if the option exists within the country, and suggested internal Ministry of Health staffers determined a Canadian option exists.

“From what I understand of this it was two conflicting, not very conflicting, but two differences of opinions from physicians on this on whether they could go to another jurisdiction to be able to get that,” he said.

“But again, I’m happy to sit down with this individual with this family to be able to discuss if there’s updates. What’s happened since I met with them in April is there’s been some correspondence back and forth to my office.”

Merriman said his information on the matter came from a “clinical advisory group”.

“They’re the ones that are the experts in this on whether it can be done in our province, in our country, or outside the country, they’re the ones who advised there is an opportunity outside the province to get this specific, very rare surgery done,” he said, though he did not specify exactly where.

Comments