One of the top-polling mayoral candidates insinuated late in the running that the campaign is all about the money.

In his opening comments during a mayor debate hosted by CBC on Thursday, Jeff Davison accused both of his opponents, Jeromy Farkas and Jyoti Gondek, of having millions of dollars behind them.

“Jeromy has the backing of millions from the wealthy elite who don’t value the needs, wants and desires of the average Calgarian family, and Jyoti has the backing of $1.7 million from union bosses trying to buy her way to the mayor’s chair,” Davison said.

Farkas pointed to the “incredible support of grassroots donors” when asked about the recent full wrap advertisement on the local broadsheet newspaper.

But according to calculations based on the donor list on his website, Farkas may have already amassed a $1.38-million war chest during this election.

Digging through the donor lists the three candidates have published showed differences in how they reported.

Farkas’ list excludes full first names, contribution denominations differ between Farkas’ and Davison’s lists, and Gondek’s list only has names.

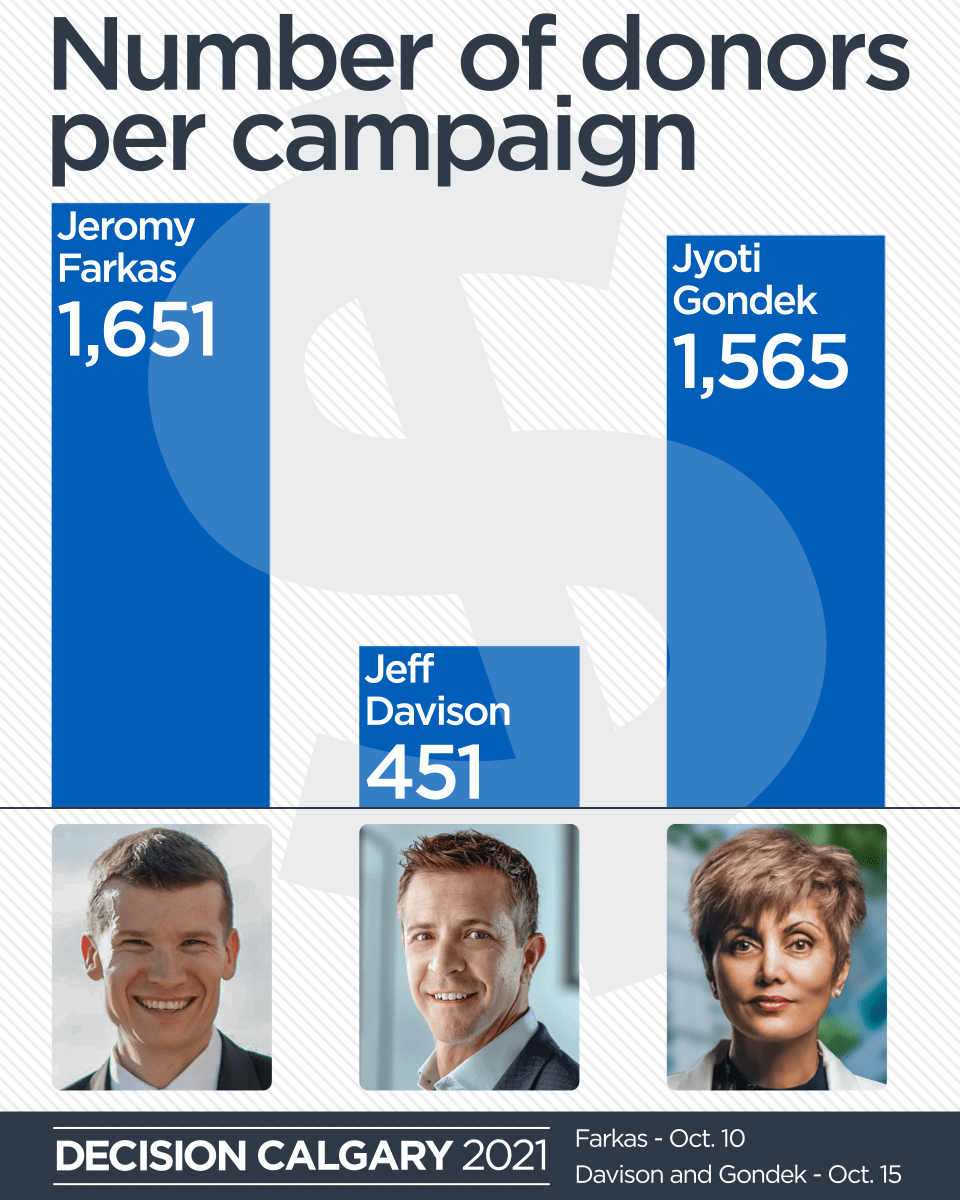

More people have donated to the Farkas campaign than Davison’s or Gondek’s.

Farkas’s campaign had 1,651 as of Oct. 10. As of Oct. 15, Gondek’s campaign was close behind with 1,565. And Davison’s campaign was trailing with just 451 total.

Donors listed on the Gondek website don’t have donation ranges, but the Davison and Farkas ones do, in different ranges.

According to Global News calculations based on their reporting, Farkas’ campaign has raised a minimum of $190,551 and a possible maximum of $1.38 million.

Farkas didn’t know how much had been raised when asked on Friday, but did say that some of his donors had made repeat donations.

“I’m so impressed with the amount of grassroots support that we’ve been able to earn… nearly 2,000 donations of $100 or less,” Farkas said.

“That’s an incredible momentum and milestone our campaign was able to reach.”

Farkas’ campaign told Global News its goal is to match the fundraising done by registered third-party advertiser (TPA) Calgary’s Future: $1.7 million.

Davison’s campaign manager Kelley Charlebois declined to answer how much they had raised, saying it could give a competitive advantage to other campaigns, but did say contribution levels were lower than they anticipated.

“I’m actually pleased with the number of donors and to a degree pleased with the donation amounts that those donors have given,” Charlebois said. “But of course, you budget at a target. Our targets were based on previous campaigns.”

“It just requires you to adjust your expectations and your plans accordingly.”

- Alberta to introduce stiffer penalties, regulations for towing industry: ‘This has teeth’

- Alberta family details ‘heartbreaking’ predatory towing experience, hopes for change

- Calgary police officer dismissed for sexually exploiting a female colleague

- Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump heritage site enjoys boost after shout out on ‘The Pitt’

Gondek’s campaign manager was upfront with how much he expected to raise before election day.

Get breaking National news

“We’ll finish up probably $600,000 to $650,000 — a very meaningful number,” Stephen Carter said Friday. “But when you compare it to the overall size of the population, it’s about 50 cents per person and communicating with the entire city of Calgary for 50 cents is a lot of work.

“But keep in mind, the number one reason why people don’t vote is they say they don’t have enough information.”

History repeating?

In 2017, Bill Smith famously raised more than $916,000 but still lost the election to Naheed Nenshi, who raised just more than $529,000 that year.

But since that election, the Local Authorities Elections Act (LAEA) — provincial legislation governing how much and who can donate to municipal election campaigns — changed.

In 2018, the province disallowed corporations and unions from donating, and capped the individual donation limit to $4,000 to all campaigns.

In 2020, Bill 29 upped that individual contribution limit to $5,000 per campaign.

“Different rules produce different behaviour,” Dr. Lisa Young, professor at the School of Public Policy, said.

“And so if we’re trying to make sense of what’s going on in this particular campaign, we have to do that in the context of these rules.

“The context really matters.”

Young said we’re now seeing the intended and unintended effects of changes to the municipal election legislation.

“When the act was introduced, the first assumption was that, for individuals who were intent on having an influence on the campaign in some way, there was going to be the possibility to give the maximum amount across many candidates, essentially hedging their bets,” the University of Calgary professor said.

“But the other piece of this, and the one that I think has become clearer as we’ve lived with the act, is the ability of contributors to give to third parties and to achieve their objectives that way.”

The result of disallowing corporate and union donations to campaigns, third-party advertisers must be registered if they spend or receive more than $1,000 in election advertising.

TPAs, akin to political action committees (PACs) south of the border, don’t have to disclose who their donors are during the election, but some are volunteering the info. And under recent changes to the LAEA, the cap on donations to TPAs is $30,000.

Both Farkas, Gondek and Davison have received endorsements from various TPAs, and all have disavowed them.

But that hasn’t stopped both Davison and Farkas from spreading the misinformation that candidates endorsed by TPAs are doing things like “trying to buy her way to the mayor’s chair.”

“No corporate or union money can come into our campaign at all, despite the fact that Jeromy Farkas is saying that we had $1.7 million,” Carter said. “Jeromy’s just simply lying.”

The support from a TPA like Calgary’s Future also wasn’t very useful for Gondek’s campaign manager.

“Calgary’s Future has run one (Facebook) ad for us. One ad with $6,000 behind it. My Facebook budget is $48,000.”

Carter said Gondek’s campaign had been approached by people interested in setting up a TPA to support her.

“We said no,” Carter told Global News.

“They said, ‘You know, I can make a TPA. We can get three donors and it’s $90,000. Ninety-thousand dollars is real money in this campaign.

“And we said no.”

Despite running against each other in this campaign, the past nine months of election have united the three candidates in one thing: the desire to change the campaign finance legislation.

Campaign expenses

Campaigns have to carefully choose how best to get information about their candidates into the hands and heads of voters.

Farkas’ campaign has stood out from the other three in being able to purchase more than just lawn signs. They’ve purchased advertising on radio, television and bus benches. Even readers of the Calgary Herald were met with Farkas’ face on the cover Thursday.

“It’s very tough to run a campaign, especially during COVID-19,” Farkas said, mentioning things like social media campaigns.

“Campaigning is very complicated these days, especially when you’re running as an independent and you don’t have a party system behind you.”

Most of the 127 candidates running for council and mayor have had signs defaced or damaged, eating into their sign budget.

Davison’s campaign got caught in scandal when Calgary Tomorrow, a TPA that has endorsed only Davison, printed lawn signs and other campaign material supporting him.

Charlebois said he’s unaware of how much was spent or how many signs were printed.

“It’s not something I’d be aware of, frankly,” Charlebois told Global News, echoing earlier comments made by his candidate. He also said the campaign hasn’t done a valuation for those signs.

But Charlebois said he and the campaign were aware of the legislated separation between candidate and TPA enshrined in the LAEA.

“Of far greater importance to me was understanding the legislative requirements for somebody running for mayor. But certainly, we’re aware of what the TPA rules are.”

The Davison campaign manager said they have been spending their donation money on things like brochures, advertising in community newsletters, and online and radio ads.

The Gondek campaign has handed out 1.6 million brochures over subsequent waves, have more than 7,000 signs throughout the city, and have a “significant” purchase of Facebook ads.

But they haven’t been able to purchase ad buys on television or radio.

“We couldn’t afford it,” Carter said.

He said the campaign relegated larger media buys to near the end of the campaign, especially to help with the “get out the vote” effort.

Instead of radio, they’re doing another drop of tens of thousands of flyers.

“When I had a choice between direct or broadcast, I chose direct every time,” Carter said.

“So we’ll see whether or not that pays dividends.”

Young said the amount of advertising in more expensive methods, like radio, television or billboards, can be an indicator of a campaign’s budget.

“The activity, especially in these last days of the campaign, is sort of an indicator of who’s got money available to them,” she said.

“Of course, you have to be careful under these rules to see whether the signs or the radio ads are paid for by the candidate or by a third party on their behalf.”

Comments