Edmonton’s Muslim community can be traced back decades, but in recent months, the community has felt targeted and “othered” after a slew of disturbing, violent attacks.

The words of three generations of Muslim-Canadians give insight into the deep sense of self and confidence the community maintains, despite moments that have shocked and disturbed them.

A young woman honing her voice against hate, a working professional who helps others find their place, and a lifelong volunteer — each has helped shape the fabric of Edmonton.

String of attacks

Amal Mohamud is a young, Black, Muslim woman.

She knows that makes her a target. But it also makes her feel powerful.

“I am not ashamed of any part of my identity. I own all parts of it,” she said.

In particular, the symbol that has drawn hate toward Muslim women is a symbol of power for Mohamud.

“When I put the hijab on now, I do get a little nervous … but it’s never crossed my mind to take it off to make things easier,” she said. “It makes me feel beautiful. It brings me closer to my religion. It’s a constant reminder to be a better person. I don’t see myself removing it for anyone to make them more comfortable.”

That doesn’t mean Mohamud isn’t feeling the weight of a string of disturbing physical and verbal assaults, directed mainly at Black, Muslim women wearing a hijab or burqa.

Edmonton police reported at least nine verbal or physical incidents from December 2020 to August 2021. They include a series of separate assaults within days of one another in December.

In a June incident, a woman was grabbed by the hijab in St. Albert and knocked unconscious.

Police reported the attacker then pulled out a knife and “knocked (a) second female to the ground and held her down with the knife against her throat while he continued to threaten them with racial slurs.”

Said Mohamud: “I feel the attacks have always been there, but people are more vocal about it now.”

A new level of horror to comprehend within the community had come earlier in June: A deadly, intentional attack in Ontario that killed four members of the same family.

“At the end of the day, (Canada) is my home. I shouldn’t be feeling this way,” Mohamud said.

New beginnings

In 1938, in the midst of the Great Depression, the early Muslim pioneers opened Canada’s first mosque, the Al Rashid Mosque, in Edmonton. A new mosque was built in 1982 to accommodate the expanding community, but the old one stands as a historic building in Fort Edmonton Park.

Get breaking National news

Harriett Shaben first stepped inside the Al Rashid Mosque when she was 20 years old. It was 1960, and Shaben had just gotten married.

She remembered a swell of emotions as she entered. It was the first time she had visited a mosque.

She’s been inside much grander and larger mosques around the world since, but Al Rashid holds a special space in her memory.

“(The Muslim community) was a small group at one time. My parents were immigrants (and I grew up in Nova Scotia). Somehow, we managed to fit in,” she said.

“I remember in Nova Scotia, my father doing a lot of explaining to people about who we were … and they accepted us.”

In Edmonton, she quickly became an active volunteer and community member.

“By 1911, there were approximately 1,500 Muslims in Canada. Edmonton, Alta., became a major centre for Arab Muslim pioneers and often the final stop in their journey across Canada,” reads a historical paper from the Al Rashid Mosque.

“These generations balance an identity that both embraces Islam and their reality as born Canadians,” reads another Al Rashid document, detailing its history.

Shaben has recently witnessed people in Edmonton verbally attacking Muslim girls and women wearing a hijab.

“I have noticed it just in the last couple of years. Never before,” she said. “It’s very sad. Maybe if people understood (the Muslim faith) better, maybe they would feel differently.

“I never had to explain that I was a Muslim. There was no reason to … I am what I am. It really is awful to see what it happening right now.”

Most Canadians see racism as serious problem: poll

Is the rest of Canada recognizing what Muslim-Canadians are experiencing?

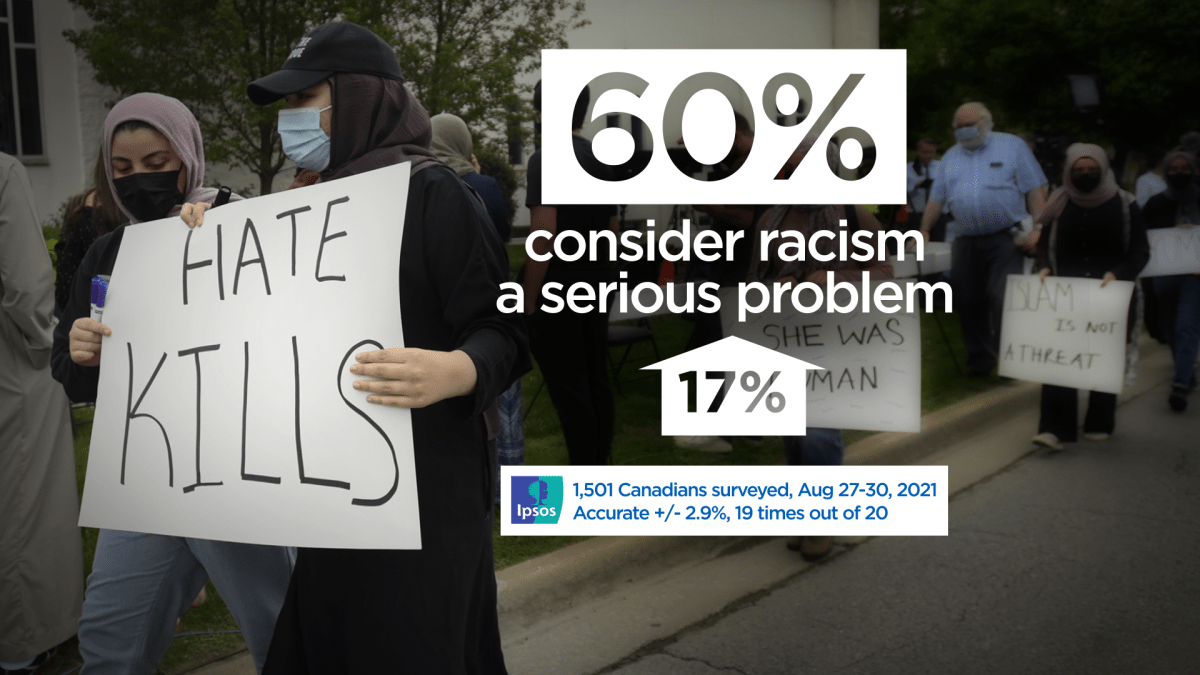

Six in 10 Canadians believe to some degree that racism is a serious problem facing the country, according to a recent Ipsos poll conducted on behalf of Global News.

Though unchanged from the same time last year, this proportion is a “considerable jump” from Canadians’ perceptions of racism pre-pandemic. In 2019, 43 per cent of Canadians polled said they believed in some way that racism was a serious problem.

“Increased awareness of anti-Asian hate crimes during the pandemic, continued mistreatment against Indigenous Canadians, domestic terrorism against Muslim Canadians and discrimination against Black Canadians have certainly contributed to the idea that Canada is not making much progress in tackling racism,” Ipsos CEO Darrell Bricker said.

Black, Indigenous and people of colour tended to see the issue as more pressing, according to the poll.

“Those who identify in a way other than only ‘white’ are more likely to say racism is ‘one of the most serious problems’ facing the country (27 per cent versus 17 per cent), whereas those identifying as only ‘white’ are more likely to choose a less intense stance, saying it is a ‘fairly serious problem’ (40 per cent versus 31 per cent),” the poll results read.

When asked whether racism has increased in their community over the past five years, a quarter (24 per cent) of Canadians said it has — a four-point (20 per cent) increase from May 2019.

Again, the community directly impacted by racism had higher numbers, with the proportion climbing to 33 per cent (compared to the 21 per cent among those self-identifying as only “white”).

Finding your voice

Sana Atiq-Omar is a mental health therapist and said in her practice, she sees young people feeling they must choose between their roots outside of Canada and their Canadian identity.

“It’s this question of, ‘Am I looking too Muslim and thus less Canadian?’ Or they say, ‘We watch the hockey games, we drink the Tim Hortons, we wear the jerseys,’ and yet we are still attacked while outside wearing the hijab,” she said.

“I think my generation and the generation after me — the difference is that we are not afraid to be who we are and have duality in our identity, to be very Canadian, very Muslim, very Indo-Pakistani. I think that level of confidence maybe wasn’t there in the first generation that came.”

Atiq-Omar spoke of the pride she feels toward the Muslim-Canadians who “set the path that (she) is walking on today.”

Some of her earliest memories are of her and her mom volunteering at the local mosque.

“We were helping Bosnian refugees at the time. We were grocery shopping for them and helping them get settled. It was just sort of part of your upbringing. You were just raised with other community members doing things for one another.

“I feel a sense of responsibility to carry that torch forward, for our children to learn that,” she said. “I hope to see it only increase for my children and future generations — that you very much feel that you belong here and deserve to be here as anybody else.”

She said she has open conversations about Islamophobia and “othering” with her two boys, at an age-appropriate level.

“Especially when I started wearing the hijab. We have conversations about how ‘Mommy is treated differently sometimes.'”

Atiq-Omar said there’s a collective fear within the community, but also exhaustion at having to be their own advocates.

“It’s like an extra burden on our women,” she said. “It’s not on us to point out ‘What’s the issue?’ but also ‘What’s the solution?’ It should be on the policymakers.”

Next generation

Mohamud’s generation — the Millennials and Generation Z — have found new ways to get their voices out. She said she’s found a platform through social media and by participating in social movements such as Black Lives Matter.

“I think it’s really important for us to make a difference and stand up for ourselves, because if we don’t do it, who will?” she said. “In order to make a change, we need to start having a conversation about what’s going on. If we don’t talk about it, obviously we aren’t going to know what’s happening.

“It doesn’t make sense for us to feel like the outcasts.”

She went on: “I feel like the generations of past would be so proud of the generation today — just seeing us stand strong. No matter what happens, we keep moving forward.”

The Ipsos poll was conducted between Aug. 27 and Aug. 30, 2021, with a sample of 1,501 people interviewed online. The poll is accurate to within +/– 2.9 percentage points, 19 times out of 20.

- Khamenei’s death met with ‘jubilation’ among Iranian-Canadians: Liberal MP

- ‘Something just went off’: Canadians in Middle East describe ‘surreal’ Iran missile strikes

- ‘At first I cried’: How Iranian Canadians are reacting to the U.S. strikes in Iran

- Iran begins search for new leader; U.S. military says 3 service members killed

Comments

Comments closed.

Due to the sensitive and/or legal subject matter of some of the content on globalnews.ca, we reserve the ability to disable comments from time to time.

Please see our Commenting Policy for more.