Canada Day protests through downtown Winnipeg culminated in the toppling of a statue of Queen Victoria at the Manitoba legislature, and local Indigenous leaders are speaking out about the incident.

The statue’s head was also removed. It was retrieved Friday from the river behind the legislature by a man in a kayak.

A smaller statue of Queen Elizabeth II on the grounds was also taken down.

Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs (AMC) Grand Chief Arlen Dumas told 680 CJOB he was part of a march along Portage Avenue but wasn’t at the legislative grounds when the statues fell.

Dumas said he doesn’t condone the incident, but said emotions were high at the march, in recognition of more than 1,000 children recently discovered in unmarked graves at residential schools across the country.

“There’s a lot of anger, there’s a lot of sadness, there’s a lot of grief. It’s a whole multitude of emotions and we’ve got to make sure that we’re giving people the proper resources and the proper supports,” he said.

“I believe there would have been other ways to address the issues of those statues and what they represent, but fundamentally, statues can be replaced but those lost children that we’re finding can never be.

“The trauma that’s been inflicted on people isn’t going to go away easily.”

Dumas said a positive takeaway from Thursday’s march was the overwhelming support from Winnipeggers of all walks of life.

“I think yesterday was an incredible show of solidarity,” he said.

“I truly appreciate all the people who walked down Portage with us. It was truly a sea of orange; there were people of all backgrounds there.”

Chief Glenn Hudson of Peguis First Nation told Global News Winnipeg Morning he was also encouraged by the diverse support on Thursday.

“A lot of people walked with us — not only Indigenous people, but a lot of non-Indigenous people, and it was great to see that level of support,” he said.

Get breaking National news

“For the people that were there — (there was) a lot of pride in terms of walking together and working together. I think it’s so important for us as First Nations, as Indigenous people … like we always have, we reach out to other communities and we work together in finding solutions in going forward.”

Hudson said he found the toppling of the statues “disappointing,” and said in his conversations with other chiefs, many agreed with him — but he understands the anger and frustration that caused it.

- Real Canadian Superstore fined for ‘misleading’ Product of Canada displays

- Danielle Smith promises Alberta referendum over immigration, Constitution changes

- ‘No reason to continue discussing’: Ontario mayor wants Andrew’s name dropped

- Canadians say U.S. no longer an ally, is bigger threat than Russia: poll

“It’s something certainly that I wouldn’t promote,” he said, “but when, you know, your family, your parents, your grandparents and in cases some children didn’t even come home … there’s anger, there’s frustration.

“I know the people there at the (legislature) looked like a younger crowd and certainly those that carried out that act were a younger group.

“They’re frustrated, they’re angry, but they have to understand there’s a process in terms of addressing these outstanding issues.”

Hudson said he’s hopeful this outpouring of support can lead to Indigenous people and government sitting down and working together to fulfill treaty obligations and “make this a better country than what has been shown in the past.”

In a statement Friday, Manitoba Premier Brian Pallister condemned the removal of the statues.

“The actions by individuals to vandalize public property at the Manitoba Legislative Building July 1 are unacceptable,” Pallister said.

“They are a major setback for those who are working toward real reconciliation and do nothing to advance this important goal.

Those who commit acts of violence will be pursued actively in the courts. All leaders in Manitoba must strongly condemn acts of violence and vandalism, and at the same time, we must come together to meaningfully advance reconciliation.”

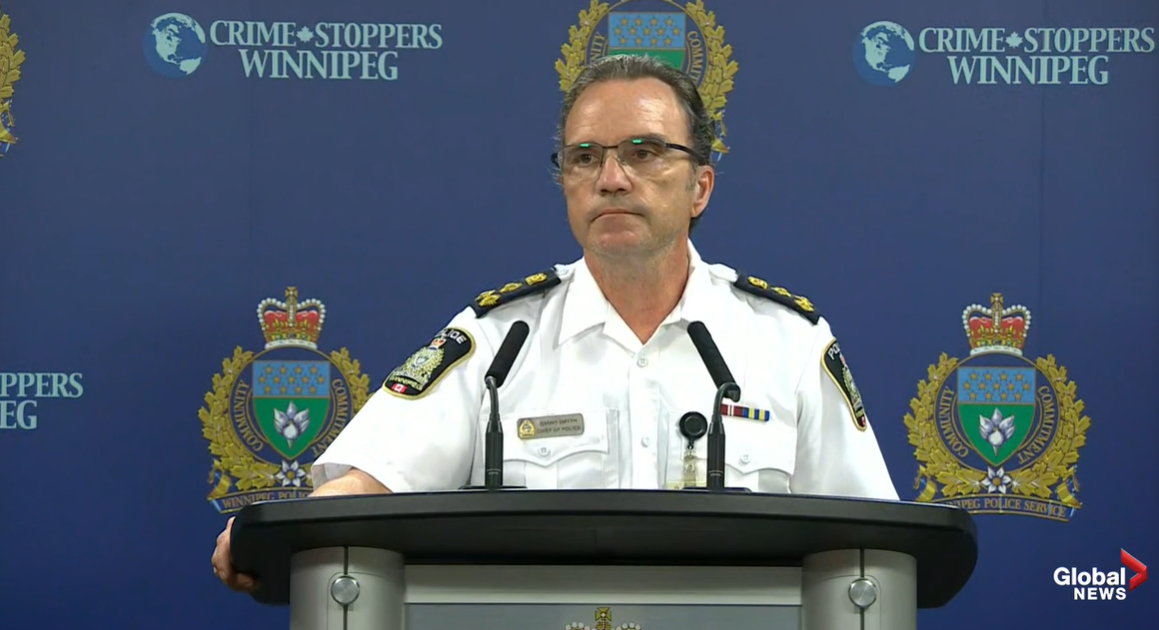

Winnipeg police chief Danny Smyth spoke to media Friday afternoon and said police had been working days in advance with march organizers — of both marches that happened July 1 — to ensure a safe and peaceful event.

The overwhelming majority of participants, he said, were peaceful, but a risk of any large gathering is that there are some within the crowd with different intentions.

Smyth said police, while on scene as the statues were toppled, didn’t get involved in the interest of keeping things safe for those in attendance.

“We did not want to further incite the crowd that had gathered. I commend our members for their professionalism and their ability to preserve a safe environment,” he said, “and later for their ability to deescalate the situation.”

Smyth said some officers were assaulted and spit on at the event, as well as several police cars damaged by rocks and paint.

Police are continuing to investigate.

“We will be investigating to determine who was involved. Everyone knows the (legislative) grounds have multiple security cameras.”

University of Manitoba ethicist Arthur Schafer told Global News there are some occasions where something as dramatic as toppling a statue could be effective, but he didn’t think that was the case here.

“I think it was counterproductive, because we’re talking about the toppling of the statue instead of talking about the huge numbers of people across the country wearing orange shirts and demonstrating their solidarity with First Nations,” said Schafer, director of the U of M’s Centre for Professional and Applied Ethics.

“For example, if an attempt to promote social justice or to rectify a profound injustice is being ignored, then you may want to engage in a dramatic gesture — the symbolism of toppling a statue.

“If you do that, it should be well-directed, so that the statue you topple is directly related to the issue so people can understand the symbolism.”

Schafer said as there was already overwhelming attention focused on the cause, with thousands of peaceful marchers, the toppling of the statues wasn’t necessary. The incident, he said, put more focus on the small group of people involved than on the larger cause being protested.

The Manitoba government was planning to erect a statue of Chief Peguis on the legislature grounds. The move, announced last October, is aimed at commemorating the signing of the first treaty in Western Canada in 1817.

–With files from The Canadian Press and Gabrielle Marchand

.jpg?h=article-hero-560-keepratio&w=article-hero-small-keepratio&crop=1&quality=70&strip=all)

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.