A single insolvent oil company from Alberta has created a five-fold increase in the number of orphaned wells to safely shut down and seal in Saskatchewan — and has left $31 million in clean-up costs and unpaid bills.

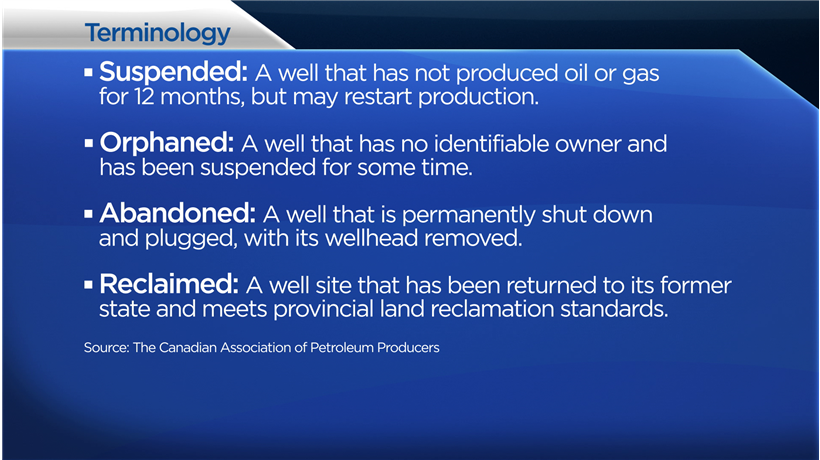

Calgary-based Bow River Energy Ltd., which sought bankruptcy protection in late 2020, has 671 orphaned oil and gas sites in the west-central part of the province. Of them, 394 require abandonment and reclamation while an additional 141 require just reclamation, according to the Saskatchewan Ministry of Energy and Resources.

The ministry confirms it is the largest-ever group of sites from a single company taken into the province’s Orphan Well Fund, and could cost up to $25 million to clean up over two to three years.

In addition, a long line of creditors is owed more than $6 million, including farmers, ranchers, small businesses, First Nations, rural municipalities — and the Saskatchewan government, itself.

It may be just the tip of an approaching iceberg, says industry expert Ken Gordey, who spent the first half of his career developing oilfields and now the latter half cleaning them up.

“Letting it get to that point is what the issue is,” he says. “It should have never got to this point.

“We have to turn around and do a refocus here.”

- Federal government raises concerns over OpenAI safety measures after B.C. tragedy

- Free room and board? 60% of Canadian parents to offer it during post-secondary

- Ipsos poll suggests Canada more united than in 2019, despite Alberta tensions

- Indigenous leaders outline priorities for spring sitting of Parliament

Wider potential problem

This is part of a much wider potential problem in Saskatchewan, where there are some 75,000 inactive and abandoned wells in the field, says Bill Kilgannon, the executive director of University of Alberta’s Parkland Institute, which studies the oil and gas industry in Western Canada.

Many are owned by small companies that buy up properties from major oil companies as the wells begin to decline. And while major oil companies have benefited from an upturn in oil prices, the future is less secure for smaller oil and gas firms, says Kilgannon.

As large producers shift to renewables and download aging oil infrastructure to ever-smaller companies, the risk of scenarios like Bow River increases, he says.

A review of Bow River company and court documents reveals this pattern. Founded in 2013 on a purchase of natural gas wells from NuVista Energy, Bow River expanded in 2017, acquiring former Husky Oil wells and a sour gas processing plant for $15.8 million.

The fledgling company specialized in buying up “mature” oil and gas assets and using horizontal drilling to reach remaining pockets of oil and gas, Bow River co-founder and chief financial officer Daniel Belot stated in a court affidavit.

However, Bow River struggled from the beginning to pay debts amid fluctuating oil prices, according to Belot’s affidavit.

“As a junior energy producer, the company is highly dependent on the price of oil and gas to maintain viable and well-capitalized operations,” he wrote.

Get breaking National news

Bow River representatives met with the provincial government several times between 2018 and 2020 seeking relief from Crown land rent and other fees, without success.

The company stopped paying rental fees in November 2018 “as part of its cost-reduction measures due to the then declining commodity prices,” Belot wrote. They ceased paying royalties in February 2020.

Also weighing down Bow River’s balance sheet was an estimated $62 to $81 million future liability for decommissioning wells not only in Saskatchewan but Alberta, as well.

Global News attempted to reach out to Belot by phone and email but did not receive a response.

“That’s the biggest problem we have in the Canadian oil field; we do not hold the junior oil companies to the fire before we go transferring licenses,” says Gordey. “And we also don’t hold the major (oil companies) responsible for the liability prior to that transfer.”

‘Every orphaned well will be cleaned up’

Saskatchewan Energy Minister Bronwyn Eyre says approval to transfer well licences during a merger involves “a complicated ratio that takes into account a company’s strength overall, solvency overall and assets versus debts.”

The government is looking to strengthen its Licensee Liability Rating program “to make sure that we have an absolutely organic sense of net corporate health to make sure that we take into account the fullest picture possible, the full inventory of assets across provinces, that we look at annual retirement of a certain percentage of wells.”

Eyre says that although there have been increased mergers during a challenging time, the province has safeguards to manage the risk and protect taxpayers.

“In Saskatchewan, it’s important to recognize every orphaned well will be cleaned up,” Eyre says. “That’s been the case and it is going to be the case going forward.”

Created in 2010, the Orphan Well Fund is supported by an annual fee paid by oil and gas companies operating in the province. That fee will be increased to help cover the Bow River costs, the ministry confirmed in an email.

“Even in the worst-case scenario that every company, every oil and gas company went bankrupt tomorrow in the province, which of course is never going to happen, the estimated $4 billion dollars in clean up would be immediately offset by $13 billion dollars in assets,” says Eyre.

As well, last April the federal government announced $400 million in assistance for struggling companies to properly abandon wells in Saskatchewan, as a way to avoid more Bow Rivers.

“We can never guarantee that companies will never go insolvent, but we can manage the risk,” she says.

“We have a strong program, we have a strong regulatory structure. I’m very proud of the regulatory structure and taxpayers should be as well.”

In the case of Bow River’s orphaned sites, Saskatchewan estimates it will take two to three years to complete abandonment and reclamation, beginning in 2022. Eyre stresses the fund is supported by oil companies, not taxpayers, and the province also expects to receive a portion of the sale of Bow River assets.

In March of this year, the courts approved sale of Bow River’s producing wells to two energy companies, Heartland and Tallahassee.

A 2019 Supreme Court decision, referred to as the Redwater case, ruled environmental liabilities must be paid first when insolvent companies sell off their assets.

With the receivership still before the courts, Saskatchewan’s Ministry of Energy and Resources says it can’t comment on whether it anticipated collecting any money and if so, how much.

“I think it’s important to wait until the receivership process is complete because only then does the cleanup begin,” Eyre adds.

Saskatchewan is not the only one in line. The province of Alberta has been left $43.8 million in unpaid environmental liabilities. Husky Oil is still owed close to $1 million and there are 388 other creditors scattered across the country.

“It depends on (Bow River’s) ability to sell off their assets at the end of the day, as to what’s left and then who’s in line to receive how much money first,” says Kilgannon.

Creditors come calling

In Saskatchewan, court documents outline $2.2 million in unpaid taxes to rural municipalities and over $2 million in unpaid provincial royalties and fees, alongside 87 creditors owed some $2 million, from trucking companies to coffee suppliers.

Monday, the R.M. of Eye Hill, located near the Alberta-Saskatchewan border south of Lloydminster, was set to appear at Queen’s Bench in hopes of reclaiming $402,559 in unpaid taxes and additional costs, an amount the RM says is rising as time passes.

Usually, companies just get a percentage on the dollar of unpaid taxes, says Kilgannon.

“Once companies go into bankruptcy protection, it is very difficult to collect on unpaid taxes.”

The ministry stated in an email: “Powers exist under the Municipalities Act to pursue the collection of unpaid taxes. However, if landowners have concerns, they can engage with the Ministry of Energy and Resources as the energy regulator of the province.”

Left untended, orphaned and inactive wells are a hazard because they can deteriorate in time, leaking sour gas, benzene and other harmful emissions.

“Unfortunately, across the entire province of Saskatchewan, we have every kind of well known to mankind that is leaking or an issue,” said Gordey, who has worked on well sites throughout Canada and internationally. “And a lot of it has to do just with the fact that due diligence with putting the well to bed properly has never been done.”

As well, the sites create problems for farmers who have difficulty moving their seeders and other equipment around old well bores sticking up out of the ground, he says.

“Who suffers? We suffer. And that’s the sad part of it,” says Gordey, referring to the people of Saskatchewan.

“People have to realize that we own the oil,” he says. “It is our oil, it is our natural gas. And by letting other people turn around and take it out, take the money and run, and then leave us with the mess to clean up is something that is getting to be more and more critical.

“The government better start putting their foot down, and start looking at everything, or we will not have a future for our families.”

This story was researched with support from the University of Regina and the Corporate Mapping Project, which is funded by the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada. Please see the “Price of Oil” for more information on this series coordinated by the Institute for Investigative Journalism.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.