By

Jeff Semple

Global News

Published May 27, 2021

7 min read

Huseyin Celil, his pregnant wife, Kamila, and their three sons were on vacation in Uzbekistan in 2006 when they heard a knock at the door.

The Canadians from Burlington, Ont., were visiting Kamila’s parents who lived in the Uzbek capital city of Tashkent. Kamila’s mother was ill and wanted to see her grandchildren.

They opened the door to find an Uzbek police officer standing in the doorway.

“They came to my parents’ house and then they were questioning us about my husband. And we didn’t have any idea, you know, what’s going on or what they are talking about,” Kamila recalled. “And then the Uzbek authorities took our passports.”

Kamila said the family was told they could collect their Canadian passports from a government office. When the time came, Kamila said a quick goodbye to her husband as he left the house. She had no idea she wouldn’t see him again.

“I cry every day, three or four times, when I think about this case, when I think about my husband,” a sobbing Kamila told Global News.

In Episode 2 of China Rising, Where’s Huseyin?, we’ll investigate the story of Huseyin Celil, a Chinese-Canadian who has been imprisoned in China for 15 years. During that time, he hasn’t received a single consular visit from Canadian officials and his family in Canada has had no contact with him. While the Trudeau government works to secure the release of the ‘Two Michaels,’ Canadians Spavor and Kovrig, detained in China since 2018, Celil’s case rarely receives a mention.

“I think Huseyin Celil’s case is absolutely one of the most egregious — if not right now, the most egregious — instance of long term imprisonment of a Canadian citizen on completely unjust grounds,” said Alex Neve, the former Secretary General of Amnesty International Canada, who has been fighting to free Celil since his arrest in Uzbekistan in 2006.

Celil is a Uyghur Muslim. He was born in China in 1969 in the northwestern region of Xinjiang, which has long been home to China’s Uyghur Muslim minority. Relations between China’s 12 million Uyghurs and the government in Beijing have been tense for a long time. Occasionally, the conflict has erupted into violence.

In the early 1990s, there was a renewed push for independence by some Uyghur activists. Chinese authorities responded by cracking down on Muslim leaders in Xinjiang, to maintain control of the restive region.

In 1994, Celil was a young Imam, who used a megaphone to amplify the call to prayer at his mosque — standard practice in most Muslim countries, but in China it earned him 48 days in prison.

Soon after that, Celil fled the country. He was eventually granted refugee status by the United Nations and, in 2001, he and his wife Kamila started a new life in Canada. In 2005, they became Canadian citizens. But Kamila said her husband never stopped speaking out for the Uyghur people.

“He was speaking everywhere. He was not scared, you know, when he was talking about protecting his people’s rights. And then he was attending the protests in front of the Chinese consulate (in Toronto).”

Celil had long been on the radar of Chinese authorities and his family’s trip to Uzbekistan in 2006 provided an opportunity to apprehend him. A few years earlier, in 2001, Uzbekistan joined the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, along with Russia, China and a few other former-Soviet states. The organization’s goal was to work together to fight “terrorism, separatism and extremism” in member countries.

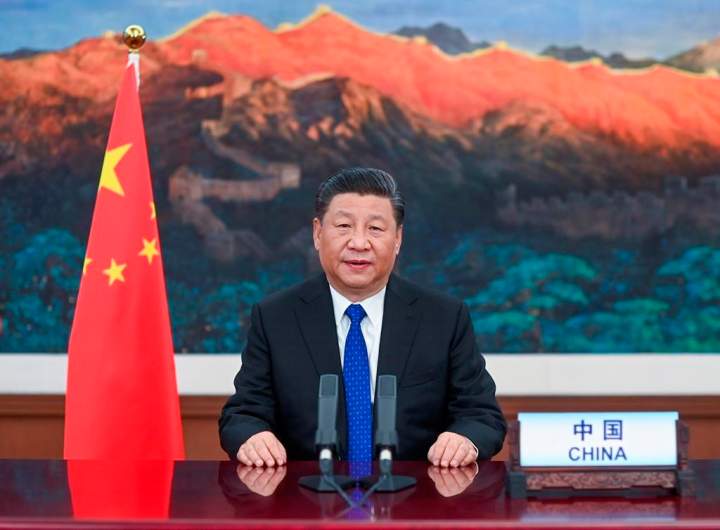

The Chinese government claimed Celil was a Uyghur separatist and a terrorist. He was arrested, extradited to China and sentenced to life in prison. Human rights groups say the Chinese government has a long history of labelling Uyghur activists as separatists and terrorists.

Beijing doesn’t recognize Celil’s dual nationality and considers his case to be an internal Chinese matter. As a result, Celil’s wife, Kamila has had no contact with him in 15 years.

“He served 15 years for nothing. He was innocent!” Kamila said. “He didn’t hurt anyone, any Chinese or any human being, he just had strong speech.”

For a time, Kamila was able to receive updates on his condition from Celil’s relatives in China, who were occasionally permitted to visit him in prison. But since 2015, despite repeated calls, none of Celil’s Uyghur family members in China has answered their phones.

Their whereabouts are unknown and Kamila fears they’ve become caught in the Chinese government’s alleged crackdown on its Muslim minority.

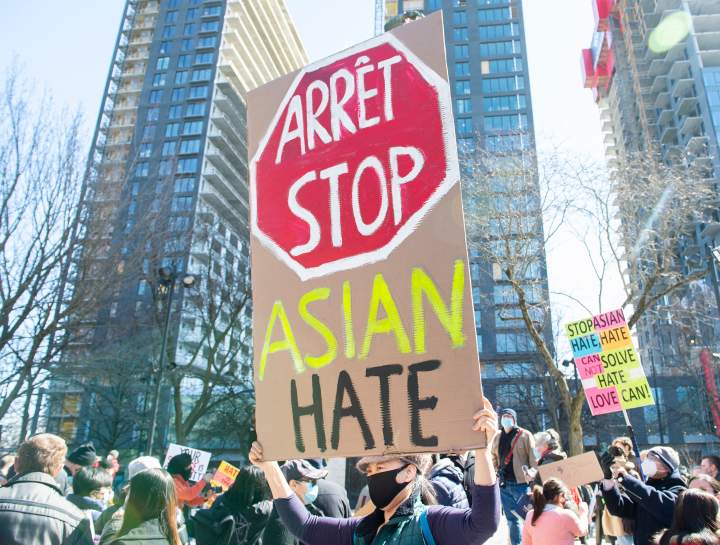

In recent years, Beijing has been accused by a long list of human rights groups, journalists, academics and governments of accelerating its crackdown on its Uyghur population, by corralling more than a million Chinese Muslims into prisons and labour camps, separating children from their families and even forcibly sterilizing Uyghur women.

Chinese officials describe the facilities as “vocational schools” and part of a highly successful de-radicalization program for religious extremists.

“I think that the Uyghur population is, for me, one of the worst mass atrocities of our time,” said Irwin Cotler, a former Canadian justice minister and attorney general who now leads the Raoul Wallenberg Center for Human Rights in Montreal.

Cotler was one of 50 global experts in international law and Chinese affairs who published a report in March, which contained first-hand accounts and testimony from dozens of Uyghur survivors — people who made it out of China’s alleged labour camps.

“Survivors have testified to forced enslavement, torture, rape, disappearance and murder,” Cotler said. The report argues the Chinese government’s alleged actions in Xinjiang have violated every single provision in the United Nations’ Convention on Genocide.

“One cannot ignore that the Uyghurs at this point are the most targeted minority since the Jews were targeted in the Holocaust in terms of what I would call mass atrocities that, taken together, are acts constituted of genocide.”

A Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson recently described the allegations that a genocide exists in Xinjiang as “the lie of the century made up by extremely anti-China forces.”

Chinese officials say the so-called labour camps in Xinjiang are needed to prevent terrorism and root out Islamist extremism.

In February, a majority of Canadian MPs voted to condemn China’s alleged mistreatment of Uyghurs as a genocide. But Prime Minister Trudeau and his cabinet abstained from the vote.

Trudeau said the word genocide is “extremely loaded” and he is not prepared to use it at this point.

Celil’s lawyer, Chris MacLeod, worries about the Trudeau government’s apparent unwillingness to take a stand against Beijing, which he believes is needed to secure Celil’s release.

“You need to be loud, you need to be vocal, and you need to call out wrongs when they occur — period. Full stop. There is no quiet diplomacy to bullies, whether they’re in the schoolyard or they’re on the international stage. And when they’ve taken one of our own, in this case, three of our own — two Michaels and Huseyin — we’ve got three Canadians; those are three good reasons to do whatever it takes to secure their release and return.”

MacLeod and Celil’s family believe the coming months could offer a rare opportunity. The ongoing imprisonment of the ‘Two Michaels’ has shone a spotlight on China’s detention of Canadians and its use of so-called ‘hostage diplomacy.’ And a growing number of Western countries, including the United States and the United Kingdom, are now openly accusing China of genocide over its treatment of Uyghurs. At the same time, Beijing is preparing to host the 2022 Winter Olympic Games, amid calls for a boycott from some governments and human rights groups.

“China’s hosting the Olympics, it’s a moment in time where China could do the right thing and release and return (Celil) on compassionate grounds,” said MacLeod.

“You’ve now got two other Canadians detained that are very high profile. You have a spotlight placed on a tragic situation. And if we can bring everyone into the fold who’s caught up in wrongful detentions in China, the goal is release and return of all three. No one left behind. No one.”

To subscribe and listen to this and other episodes of China Rising for free, click here.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.