By

Jeff Semple

Global News

Published May 13, 2021

10 min read

When Julia and Kevin Garratt were invited out to dinner on Aug. 4, 2014, they never imagined it was a trap.

The Canadian couple had lived in China for three decades. For seven years, they’d been based in the northern Chinese city of Dandong, just across the Yalu River from North Korea. The Christian aid workers ran a popular coffee shop overlooking the river and they were well-known in the community.

A Chinese acquaintance of theirs had asked them out to dinner. The family planned to send their daughter to the University of Toronto; both Julia and Kevin graduated from the university in the ’80s and were happy to answer any questions about the school and the city.

After a lavish dinner at a local seafood restaurant, Julia and Kevin said goodbye to their hosts and emerged from the private dining room to find a large crowd had gathered in the lobby. Some were pointing cameras in their direction.

“I was like, oh, let’s move out of the way. Maybe it’s a wedding,” Julia recalled. “That’s all I could think of. I wasn’t thinking it’s an abduction.”

Then two men grabbed her from behind.

She and Kevin were dragged from the restaurant lobby, forced into two separate vehicles and driven away into the night.

“Your heart’s beating a hundred miles an hour, your mind’s spinning,” Julia recalled. “I’m just like, what is going on? And the next thing you know, I’m in a cell and I’m interrogated and I’m told that I’m a spy.”

At first, the Canadians believed their arrest was a mistake. They had no idea they’d just been cast as pawns in a geopolitical chess match, their fates being determined by events unfolding 8,000 kilometres away.

In Episode 1 of China Rising, Hostage Diplomacy, we’ll examine the Chinese government’s practice of detaining political prisoners by hearing directly from Canadians who’ve become caught in the crossfire. The Garratts’ experience is eerily similar to the case of the ‘Two Michaels,’ Michael Spavor and Michael Kovrig, detained in China since December 2018. Using their stories and others as a guide, we’ll explore how Western countries, including Canada, should respond to China’s so-called ‘hostage diplomacy.’

In the weeks leading up to the Garratts’ arrest in the summer of 2014, political tensions between Beijing and Washington were beginning to bubble.

U.S. President Barack Obama and his intelligence officials were openly accusing China of launching a litany of cyberattacks — espionage and intellectual property theft — targeting U.S. companies and the military.

Canada claimed it, too, had been hit by a Chinese state-sponsored cyberattack targeting the National Research Council, the government’s scientific research agency.

China denied the allegations and challenged its accusers to provide evidence. So, the Americans did just that.

On May 19, 2014, the FBI’s John Carlin appeared before the cameras, flanked by the U.S. attorney general, to announce charges against five hackers from China with links to the Chinese military.

“For the first time, we are exposing the names and faces behind the keyboards in Shanghai used to steal from American businesses,” Carlin declared.

The FBI even produced a ‘Wanted’ poster of their five suspects. But that only underscored the futility of their efforts. All five men lived in China and no one expected the Chinese government would ever actually hand them over to the U.S. to face charges.

The Americans wanted to make an example of someone they could actually arrest. And they found their man living just a short drive north of the border in British Columbia.

Su Bin, a Chinese businessman and permanent resident of Canada, lived in Richmond, B.C., with his wife and two children, and ran an aviation technology firm.

Bin was arrested by the RCMP in June 2014 at the request of the U.S. Department of Justice. The Americans accused him of spying and hacking into the computer systems of U.S. companies with large defence contracts, such as Boeing, to steal data on military projects, including fighter jets.

But as a Canadian court considered whether to extradite Bin to the U.S., China quickly responded by sending a not-so-subtle message to make America’s northern neighbour think twice.

One month after Bin’s arrest in B.C., the Garratts were arrested in Dandong, facing almost a carbon copy of the U.S. allegations against Bin.

“It became clear that they had been arrested in retaliation for the arrest of Su Bin,” said Guy Saint-Jacques, Canada’s ambassador in Beijing at the time.

Saint-Jacques told Global News that while Chinese officials publicly denied the two cases were connected, in private they were unequivocal.

“Finally, I had a meeting and it was clear: they said, you return Mr. Su Bin and good things will happen to the Garratts. And I said, there’s absolutely no link between those cases. Mr. Su Bin is charged with very serious spying accusation. Our two Canadians were involved in humanitarian work. It makes no sense for you to detain. But they kept saying, you know our position.”

The Canadian government refused to discuss a prisoner exchange.

And so the Garratts remained in a Chinese prison.

They were separated and held in solitary confinement — alone in a cramped cell under 24-hour guard — and interrogated for six gruelling hours every day.

“I remember during those first couple of months, two or three months of interrogation, they threatened execution many times,” Kevin told Global News.

“You sit on a chair facing three officers in a small room with cameras everywhere,” Julia explained. “And then they just dig, dig, dig, dig, dig, until you almost feel like you are a criminal.”

“They’re all speaking Chinese. There’s a lot of vocabulary that is related to the legal system and to spying that we didn’t know. So you’re translating, you’re trying to think about what words to choose in Chinese to answer that won’t be misinterpreted, and then they’re writing it all down. And so it means that you’re on this tense emotional roller-coaster the whole time.”

For months, the couple had no contact with the outside world or with each other. Julia feared Kevin was dead.

“Every day I asked them, ‘Is Kevin alive?’ And every day they said, ‘We know nothing about him.’ And the truth was he was right downstairs in the same compound. We were the only two prisoners, 50 or 60 guards, but they would never give me the satisfaction of saying he was alive.”

Eventually, the Canadian embassy managed to negotiate a 30-minute meeting for Canadian officials to see the Garratts and check on their condition. That morning, Julia was escorted downstairs for breakfast. It was the first time she’d been allowed to leave her cell in three months.

As she entered the room, she heard footsteps and turned to look. It was Kevin.

“And then I fainted,” Julia recalled with a chuckle. “I literally, it was like too much emotion. And then, I don’t know what happened, somebody caught me, and then they chastised me! They said, ‘This is your treat, why did you faint?!’ As if I had a choice.”

She and Kevin were told they had 10 minutes to talk but they weren’t allowed to discuss the case.

“Kevin just said to me, ‘Julia, whatever you’re going through, whatever you’re feeling, I’m feeling it, too.’ And I took back that as a treasure back to my room, because all of a sudden I wasn’t alone. He was alive. And whatever I was going through, he was going through. And we would get through this together.”

After seven months, Julia was released on bail and eventually allowed to return to Canada. But Kevin was charged with espionage and transferred to a different prison to await his day in court.

Kevin’s trial finally came in April 2016. It was a closed hearing, which meant no spectators were permitted to attend. Ironically, the Canadians hoped that was a positive sign.

“If it was a public trial, meaning there were spectators, it will not go away. They’re going to make an example of you,” Kevin explained.

Kevin sat alone in the middle of the courtroom in front of three judges, struggling to understand what the lawyers were saying.

“The trial actually was horrible,” Kevin said. “It was an all-day trial. I hardly had a chance to speak. I said, ‘Can I talk now? Can I say something? Can I talk to my lawyer?’ And it was, no, no, no.”

At one point, in the middle of the trail, Kevin’s lawyer suddenly got up and left, explaining that he had to catch a train.

The evidence against Kevin largely centred on some photographs he’d taken of the Yalu River in front of their coffee shop, as well as the Sino-Korean Friendship Bridge connecting China with North Korea. On one occasion, Kevin had snapped a picture of a Chinese military exercise on the banks of the river.

“It was very minor, what they were saying that he had done,” said former ambassador Saint-Jacques. “But in China, you know that once you are formally charged and once your trial starts, you’re toast, because according to figures of the Chinese Supreme Court, you are found guilty 99.7 per cent of the time. So we knew that Kevin would be found guilty and would be sentenced.”

He was right. Five months after the trial began, Kevin was found guilty and was sentenced to eight years in prison.

But just when it seemed his fate was sealed, the Canadians caught a break. The Chinese hacker arrested in B.C., Su Bin, suddenly agreed to plead guilty and be extradited to the United States to serve four years in prison.

“The Chinese were taken by surprise,” said Saint-Jacques.

Meanwhile, China’s relationship with Canada was also looking up. A recently elected Canadian prime minister, Justin Trudeau, was promoting a possible free trade agreement with the Chinese, China’s first deal with a G7 country.

“The prime minister wanted to come to China. We knew also that (Chinese) Premier Li Keqiang was planning to pay a return visit to Canada. And so we said, we have to use this as a lever to bring closure to this case.”

Trudeau arrived in China on Aug. 30, 2016. The following day, he met with Li, China’s second most powerful leader. Li was scheduled to visit Canada a month later and Ambassador Saint-Jacques said they were promised news about the Garratts before then.

Sure enough, two weeks after Trudeau’s visit, Saint-Jacques received a phone call: After 775 days in detention, Kevin was free.

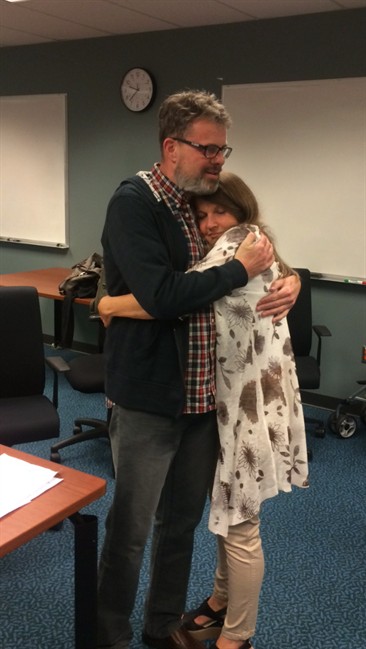

On Sept. 15, 2016, he was reunited with Julia and their family at Vancouver International Airport. The Garratts publicly thanked the governments of Prime Minister Stephen Harper and Trudeau for working to secure their release.

But they were also critical of the Canadian government.

“When we got back here, it was basically like, welcome home, goodbye. There was no psychological examination or assessment, no training, no help for us. We had to find it all on our own through our own resources and community. And that was a huge shock to us,” Julia said.

“You have to remember that your mind is completely different when you come out. Your nerves have all been rewired, your brain has been rewired, and you’re coming into a world that you don’t even recognize anymore.”

The Garratts are now working to fill that gap themselves, by supporting other political prisoners and their families. And they’ve got their work cut out for them.

More than 100 Canadians are currently detained in China, according to figures from the Global Affairs Canada. Many are dual Chinese-Canadians citizens, such as Huseyin Celil, an outspoken Uyghur Muslim who has been detained in China since 2006. On the next episode of China Rising, we’ll explore Celil’s story and speak to his Canadian wife, who fears his case has been forgotten.

To subscribe and listen to this and other episodes of China Rising for free, click here.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.