There’s a simple yardstick in personal finance about purchasing a home: buyers should aim for a property priced at four times their income or less. But average Canadians’ ability to stick to that simple rule is rapidly fading across much of the country as property values continue to soar.

In the pandemic-linked housing boom, average residential property values have become decoupled from average incomes over vast swathes of the country.

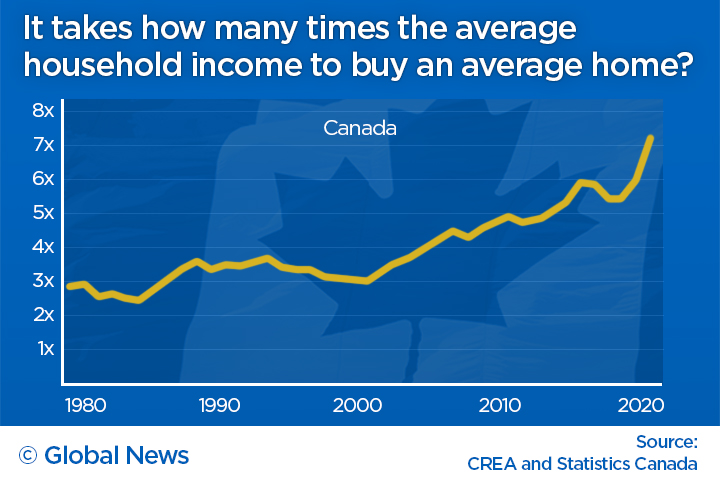

Here’s a look at average incomes relative to average home prices across markets over the last 40 years.

National statistics show the average national home price is now more than seven times the average household income, according to data from the Canadian Real Estate Association and Statistics Canada.

The average home price isn’t a perfect measure of what homebuyers are facing in the real world, as the metric can be swayed by variations in types of homes sold in a given period. Still, the numbers provide a stark picture of how rapidly affordability is eroding.

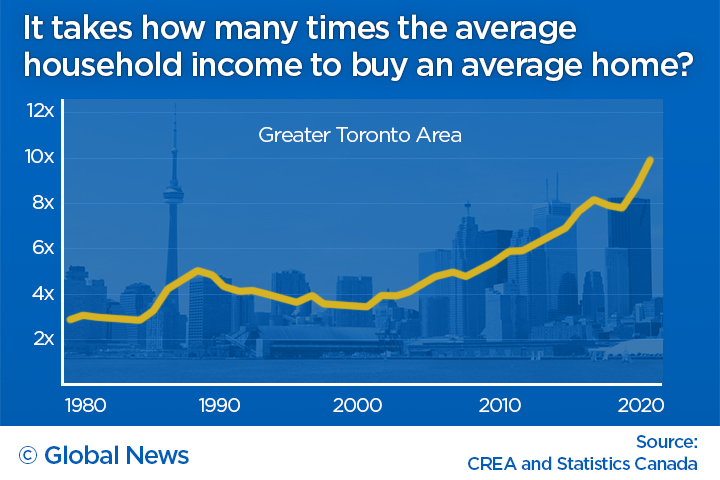

For more than a decade, home prices growing much faster than incomes was an issue largely limited to Vancouver and Toronto, two of the country’s priciest and most active real estate markets.

In Greater Vancouver, the average price of a home was close to 12 times the average local income in 2016, according to data from the Canadian Real Estate Association (CREA) and Statistics Canada.

That ratio came down a couple of notches following the implementation of provincial and federal measures aimed at cooling the housing market between the second half of 2016 and 2018. But amid the pandemic real estate frenzy, it has been growing again, the numbers show.

In Toronto, the average home price was hovering around eight times the average local household income pre-pandemic. Now, it has reached 10 times the average Torontonian income.

But the current housing extravaganza is dramatically widening the gap between home prices and incomes in a number of markets across Canada, the data shows.

In Ottawa and Montreal, for example, the average home price is now around six times local household incomes.

In Moncton, N.B., homes are still relatively affordable, but the recent jump in home prices is remarkable. In 2019, the average local home price was an eminently reasonable 2.5 times the average household provincial income. Now, an average-priced home is worth 3.5 times the average income.

The jump has been more pronounced in some of Canada’s smaller communities. In February, BMO economist Sal Guatieri noted that in Woodstock, Ont., the benchmark home price had risen “a cool” $118,200 over the previous 12 months, more than the $86,970 the median local family earned in 2018.

Get weekly money news

“We’re in a very unusual period now,” Guatieri told Global News. “You make more money sleeping in your home than working in it.”

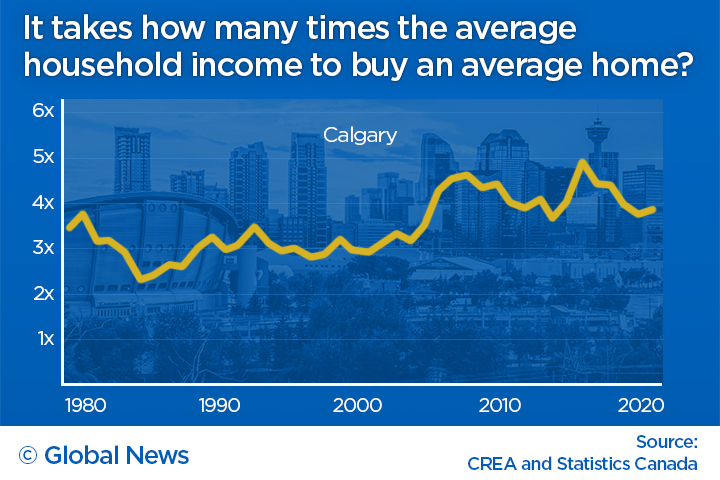

Even in Alberta, where the housing market has been dormant for years, activity is heating up. This year, Calgary saw its best March in terms of sales volumes since 2007.

The benchmark home price, at $441,900, was more than six per cent higher than last year’s levels, although property values remain below their 2014 highs, the Calgary Real Estate Board said.

Debt danger

Comparing home prices to incomes isn’t the only way to gauge affordability. Another important aspect of it is the relative size of mortgage payments. What percentage of their monthly income do homeowners with average earnings have to spend on their mortgage for an average-priced home?

In the 1980s, for example, homeowners were easily spending a whopping 50 per cent of their incomes on mortgage payments due to double-digit mortgage rates, notes Diana Petramala, senior economist at the Centre for Urban Research and Land Development at Ryerson University.

In 2020, thanks to the pandemic-driven drop in interest rates, the ratio between mortgage payments and incomes dropped to the lowest it had been since 2014, she adds.

“In large part, the frenzy we’re seeing in buying can be explained by low interest rates,” she says.

Now, though, prices have risen so much they’ve eroded the affordability gains from extra-cheap borrowing, she adds.

And for recent homebuyers, the question is what happens as interest rates rise from record lows.

“Households are more sensitive than they ever have been in the past to even small increases in interest rates,” Petramala says.

The question, Petramala says, is what will happen when many homeowners who bought in the current boom renew their mortgages five years from now.

“Even if households are paying down their equity over the next five years, if interest rates were to (climb) by one to two percentage points in (over that period), when it comes time to renew, many households who are buying now will ultimately see their mortgage payments increase,” she adds.

And “if families are house poor … that’s money that they’re not spending on restaurants and vacations and in stores,” says Mike Moffatt, senior director of policy and innovation at the Smart Prosperity Institute.

“What happens in the housing market matters and can easily spill over to the broader economy,” he adds.

The mortgage stress test, which Ottawa rolled out in two phases in 2017 and 2018, helps reduce the risk of higher borrowing costs. The test means federally regulated lenders must vet buyers’ finances to ensure they’d still be able to make mortgage payments with a higher interest rate.

But even stress-tested homeowners might feel the pinch from higher borrowing costs, Petramala says. And not all recent homebuyers had to go through the stress test, which isn’t mandatory for all lenders, Petramala notes.

What's next for home prices?

The dizzying pace of home price growth in the past several months is “quite unusual and it’s certainly unsustainable in the long run,” says Guatieri.

At some point, he adds, something will have to give. Likely, home prices will flatten out for possibly several years, allowing incomes to gradually make up some of the ground lost.

But if the current breakneck appreciation continues, “then we’re going to get into a situation where it’s almost a necessity that house prices actually fall to restore order and balance in the housing market,” Guatieri says.

The risk of a housing bust is higher in some of the smaller communities that have seen steep price appreciation, Moffatt says.

In the larger urban centres, even if home prices were to fall, they would eventually bounce back thanks to fresh housing demand stemming from population growth, Moffatt says. But in smaller towns that have seen property values climb without sustained population growth, “you could have a house price crash and never see that demand come back,” he says.

“And that’s going to be very problematic for people who bought at the top … and never see those home prices go back up again,” he says.

Charts methodology: The charts show the ratio of average home prices to average incomes. Average home prices do not take into account variations in the types of homes being sold. For incomes, we used the total before tax average income for economic families and persons not in an economic family. For the years 2020 and 2021, we assumed income growth based on the average pace of income growth between 2016 and 2019. Both home prices and income data are in 2019 dollars.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.