Tara Wood wants to be a mother.

The 39-year-old had been trying to get pregnant with rounds of intrauterine insemination (IUI) and in vitro fertilization (IVF).

At first, Wood started her “fertility journey” on her own. She froze her embryos before she met her partner.

It hasn’t been cheap.

Wood has shelled out tens of thousands of dollars.

“That number has probably gotten closer to $30,000 through all my trials and tribulations trying to conceive,” said Wood, “and still unsuccessfully.”

Wood says that’s low compared to a lot of other Canadians — and she considers herself fortunate since the province of Ontario covered her first round of IVF.

Her work benefit plan also paid for about 80 per cent of her drug costs.

“Often people will take on a loan, remortgage their house, cash in investments.”

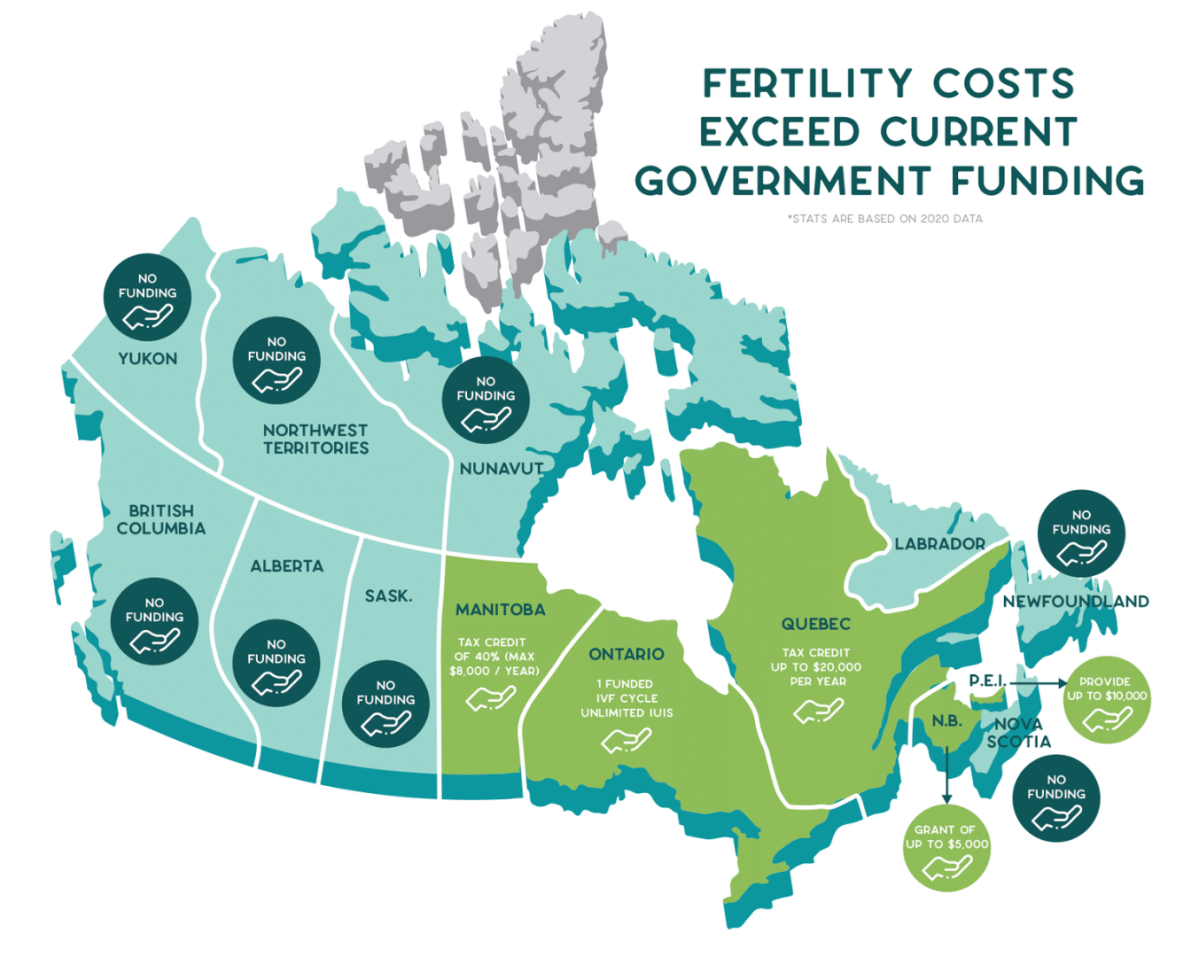

Wood, also the board president of a group called Conceivable Dreams, said public fertility funding is out of date — many provinces provide very little, if any.

“In Alberta, unfortunately no public coverage but we’re definitely working to change that,” said Wood.

Get weekly health news

Conceivable Dreams and Fertility Matters Canada have launched a national campaign called Fertility Benefits Matter.

The patient groups said the average cost of one round of IVF is $20,000 and surrogacy can cost upwards of $80,000.

The campaign pointed to a growing number of Canadian couples facing fertility challenges and insurance benefits offered by their employers have remained “shockingly the same.”

“The majority of Canadian employers provide no fertility benefits at all,” Wood said.

“I was shocked.”

The majority that do, added Wood, only cover on average up to $3,200.

Dr. Marjorie Dixon, founder of Anova Fertility & Reproductive Health in Toronto, Ont., said one in six Canadian couples struggle with fertility issues.

“It’s 15 per cent of the population — that’s what we attribute it to,” said Dixon. “It might be even greater than that by virtue of the fact that we have a very heteronormative way of looking at infertility issues.

“I think it’s critical that we recognize that our traditional view of family has evolved quite substantively.”

Dixon said now that the definition of family has changed, it’s important for employers to recognize and be inclusive of the LGBTQ community.

It’s a difficult discussion to have, added Dixon.

“An incredible stigma associated with this and some shame.”

The cost of a treatment and drugs is one thing, but Dixon said employees also need time off work to do proper monitoring to diagnose and manage cycles.

“It’s hard to be productive when you have something weighing on you and feels like it’s a tremendous burden.”

Dixon said it’s important for insurance and benefit providers to recognize how onerous fertility care can be so employees aren’t penalized or lose their jobs.

“It’s a call to action for Canadian employers and employees to speak to their employers about what’s important to them… if we are recognizing all Canadians then it behooves us to include that in the package we are putting forward as employers. I’m an employer too.”

With more Canadians choosing to have their families later in life, Wood would also like physicians to talk to patients earlier, so they are educated about fertility decline.

For now, Wood and her partner have put their fertility plans on hold.

“I can only spend so much on this.

“We will have a family one way or another,” an emotional Wood added. “Whether I deliver that child or a child comes into our life some other way has yet to be determined.”

Comments