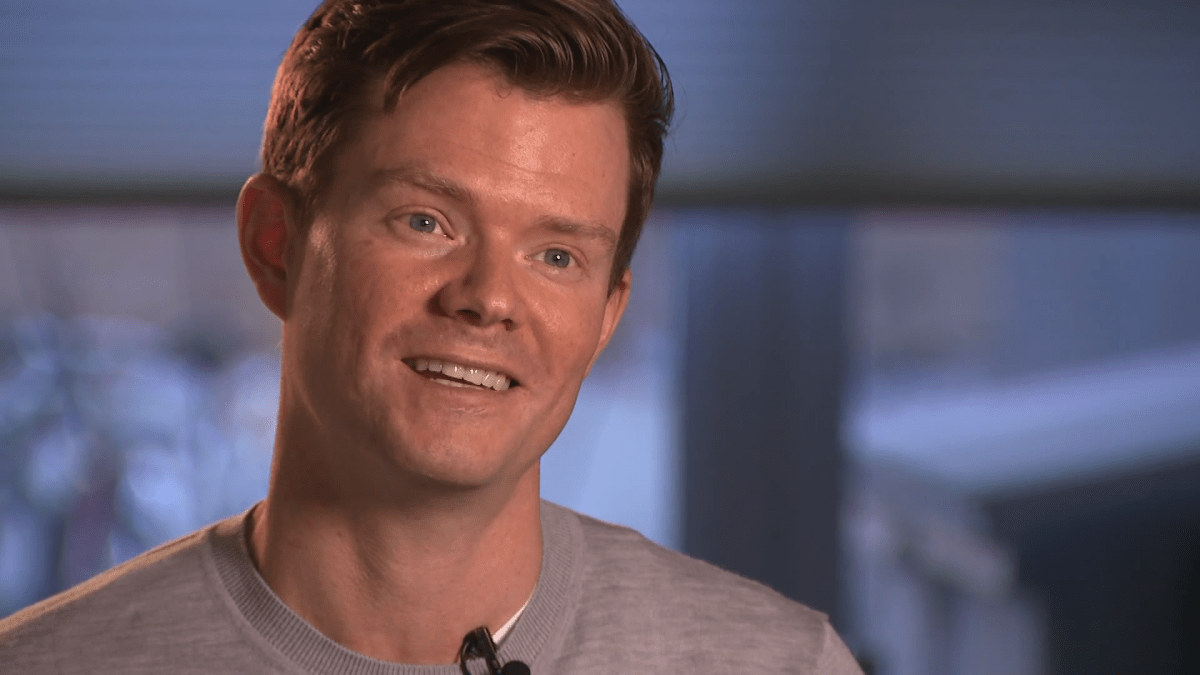

Hart Jackson’s colleagues at Sinai Health in Toronto have affectionately nicknamed him ‘the human pincushion.’

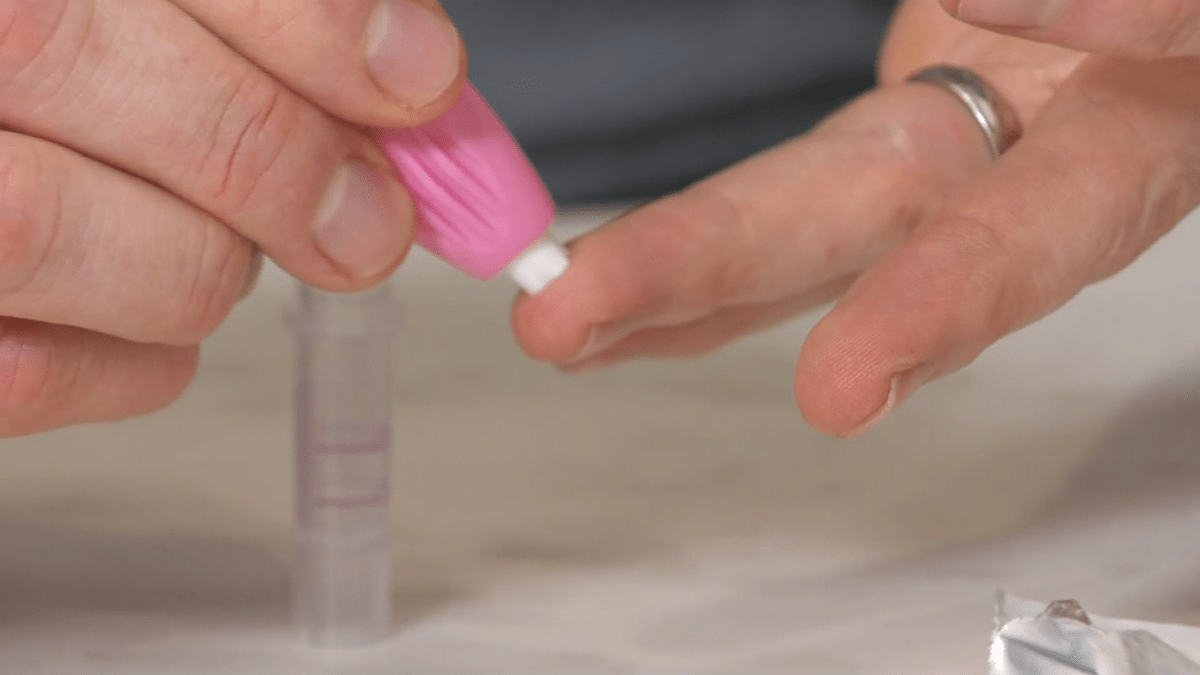

For months now, Jackson has been routinely pricking his finger to provide blood samples, in hopes of helping to answer a central question in the fight against COVID-19: How long does immunity last?

And so far, the findings appear promising.

“From all indications, I think there is a good chance that it can be longer lasting,” he said.

Jackson is an investigator at the Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute (LTRI) at Mount Sinai Hospital, specializing in breast cancer research.

After completing his training in Switzerland, Jackson moved home to Toronto in March 2020, just as the first wave of COVID-19 was crashing into Canada.

Upon arrival, he, his partner and their infant son quarantined at home as a precaution — and they’re grateful that they did.

“At about day five (of our quarantine), my partner developed a dry cough. And then it all started, where we all had slight fevers and coughs, including our six-month-old,” he recalled.

“We got the (COVID-19 test) results back very fast, which were positive and shocked all of us.”

Following his recovery in April, Jackson heard that some of his colleagues at Sinai Health and the University of Toronto were developing an antibody test to investigate whether patients who’d previously been sick with COVID-19 were immune to re-infection.

“As soon as the trial started, I was signing up right away and hoping to get involved and provide any samples that I can,” he said. “At the time, it wasn’t known how long this (immunity) was going to last.”

But now 10 months since he became infected with COVID-19, Jackson’s antibodies remain robust. And COVID-19 researchers are growing increasingly optimistic that immunity — whether acquired through infection or vaccination — will endure for some time.

“We know several people that were infected back in February and they still have quite a bit of antibodies,” said Anne-Claude Gingras, a biochemist and senior investigator at the LTRI, who developed one of the earliest COVID-19 antibodies tests.

Get daily National news

“The neutralizing antibodies decline a little bit, but they decline very, very slowly.”

Gingras points to SARS as an example of another coronavirus that can result in long-lasting immunity. “We have at least one person, the only person whose blood we have access to, who is still walking around with a fairly high level of antibodies to SARS-CoV-1, that were acquired presumably in 2003.”

Recent studies suggest the level of antibodies from COVID-19 peak after around four weeks, but remain relatively stable across age groups for at least eight months (the period for which data on the new coronavirus is available).

A study of COVID-19 in monkeys found that even relatively low antibody counts were sufficient for protection against re-infection.

“Based on the decay curves to those immune responses, we can extrapolate that immunity to the virus should last a number of years, at least to the viral variant that one was exposed to. So that’s great news,” said Jennifer Gommerman, an immunologist at the University of Toronto’s Temerty Faculty of Medicine.

The findings are fuelling calls for greater freedoms for the more than 600,000 Canadians who have recovered from COVID-19, particularly in compassionate cases. Jackson’s grandmother was living in a long-term care home in Toronto last fall when she became infected and later died from COVID-19.

Despite Jackson’s test results showing he had COVID-19 antibodies, he was not allowed to visit.

“It was difficult, as my family wasn’t able to see her much before, because the care home was on lockdown,” he said.

“The thought was, maybe I can go to the long term care home and help out, as I might be at a lower risk myself. But we’re at a stage where the rules still apply to everyone. I’m in a very rare situation.”

Some countries, though, are now rewriting those rules and adopting so-called ‘immunity passport’ systems for the growing number who have recovered from COVID-19. Hungary and Iceland, for example, are offering quarantine-free entry to foreigners who can prove that they’ve already had COVID-19.

But Gingras and her colleagues caution that a recovered COVID-19 patient’s natural immunity can vary, particularly in those who suffered only minor symptoms.

“Different people that have different symptoms’ severity have different levels of antibodies,” she said. “The question will be: the people that didn’t have bad symptoms, will their antibodies fall faster?”

Already, a small number of patients have caught COVID-19 for a second time. For that reason, Gommerman recommends that those who’ve recovered from COVID-19 should receive the vaccine regardless.

“Now, I would suggest that those people may be not be at the front of the line for getting the vaccine, because they do have immune memory to the virus. But it won’t hurt to get the vaccine,” she said, noting that the strength of a person’s natural immunity may depend on their initial exposure to the virus or ‘viral load.’

“When you’re in an elevator and you’re getting exposed to the virus, you could be getting a really big dose,” she said.

“But when you’re getting the vaccine, you’re getting it in a prescribed dose in a way that tricks the immune system to respond appropriately. Because we’re giving the same dose to everyone, the playing field is level.”

It’s less clear at this stage how long immunity derived from COVID-19 vaccines will last, but some early evidence appears promising. A study published this month in the New England Journal of Medicine found volunteers who’d received the Moderna vaccine had similar levels of antibodies after four months to those who had been infected with COVID-19.

Whether the leading vaccines will prove as effective against the new virus variants first identified in South Africa and the United Kingdom remains the subject of investigation and debate.

“The longer we wait to vaccinate the population, the more likely it is that new variants will emerge,” Gommerman warned. “We’re in a bit of a race against time and the sooner we achieve herd immunity, the better.”

Comments