Greenhouse gas emissions are at the crux of the fight against climate change.

By now we’re well aware of the effects of carbon dioxide — produced by cars, trucks and factories — and methane — much of which comes from cows in the beef and dairy industries.

But it’s a third, less talked about gas that’s taking an increasing role: nitrous oxide (N2O). A new study, published Wednesday in the scientific journal Nature, sheds light on just how much.

“The big conclusion was that nitrous oxide emissions are increasing at a rate that’s higher than the worst-case scenarios specific to that gas,” said Taylor Maavara, a postdoctoral fellow at Yale University’s School of the Environment and co-author on the study.

“It’s pretty devastating.”

Those predictive scenarios were laid out by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which uses detailed socioeconomic scenarios to depict different potential climate outcomes. The worst case: the Earth warms by three degrees by 2100. The Paris Climate Accord, which Canada committed to in 2015, aims to keep the average global temperature increase to below two degrees.

While nitrous oxide’s role in climate warming was previously known, the new research shows the gas is contributing to it more than previously thought.

The alternatives to offsetting man-made N2O are particularly challenging as they’re tangled in food production.

“CO2 is still the big issue,” Maavara said. “We’re showing that these other gases are more important than we thought. So, in a way, the need to reduce CO2 emissions is higher now because it’s potentially more feasible, and we’re going to have a hard time dealing with the other gases.

“So if we can reduce CO2, we’re going to take a step in the right direction either way.”

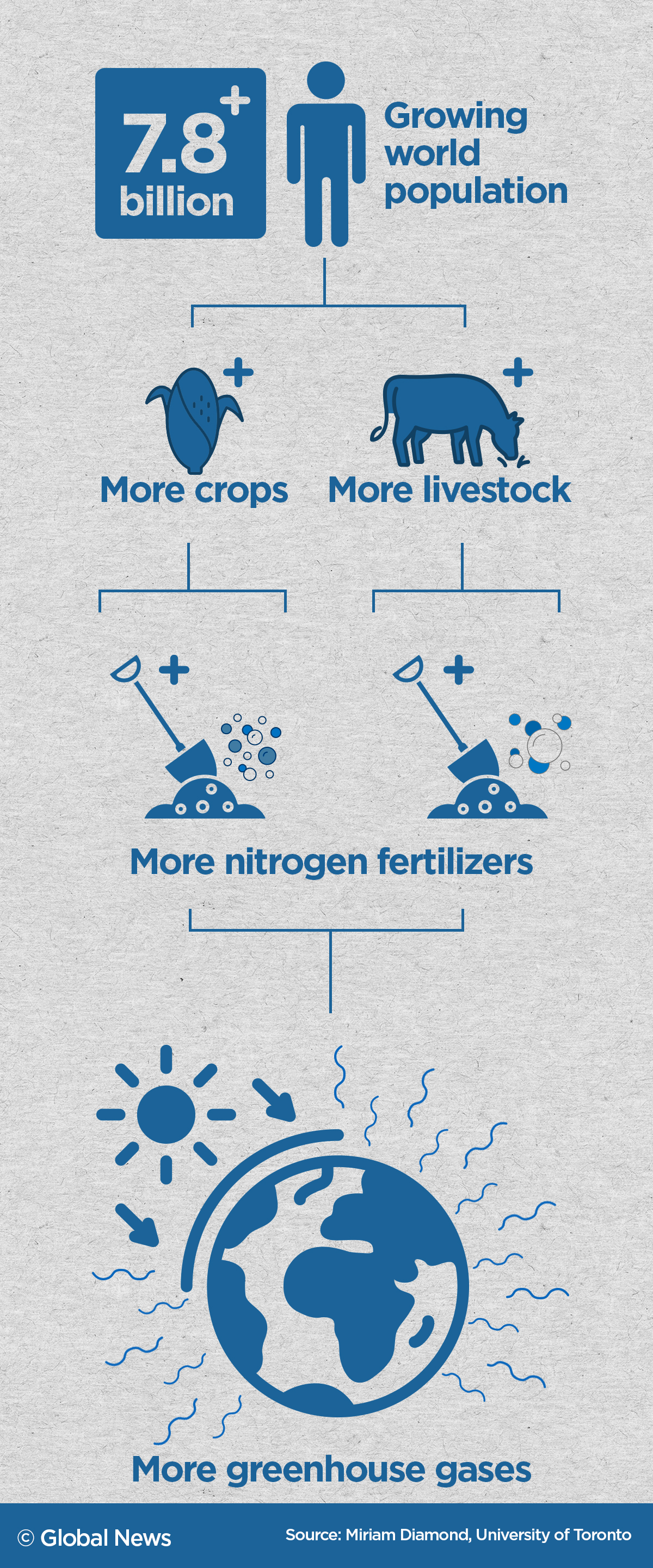

Agriculture driving emissions

Nitrous oxide is a long-lived greenhouse gas, meaning its emissions made today will be warming the atmosphere for a century.

Despite this, nitrous oxide has been somewhat overlooked in research and policies centred around agriculture and climate, said Maavara. But nitrous oxide, commonly known as “laughing gas,” is nearly 300 times more effective than CO2 at trapping heat in the atmosphere.

“It also depletes the ozone layer,” she added.

Though half of the world’s N2O occurs naturally, humans are still the dominant driver. The study found that 70 per cent of man-made N2O emissions are from a single industry — agriculture.

Synthetic fertilizers filled with nitrate and ammonium, used to bolster crop yields, are the problem. Without these fertilizers, crop yields can falter. But with them, the environmental impact can be great.

Get breaking National news

So what needs to be done?

“It’s tricky,” said Maavara, “because, obviously, we can’t stop growing food.”

Shifts in farming

“We can do a lot of things to lean away from it,” said Darrin Qualman, director of climate policy and action for the National Farmers Union. “But first, we have to decide to do them.”

This starts with the efficient use of fertilizers, he said.

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada recommends adjusting fertilizer amounts to coincide with plant needs, placing the fertilizer nearer to plant roots, and using slow-release forms of fertilizer, which can control the nitrogen release and give plants more time to absorb it.

“It’s a suite of best management practices called 4R, which stands for the right fertilizer product, in the right place, at the right time, with the right amount,” said Qualman. “If farmers do that, they could reduce fertilizer use by 20 to 30 per cent and still maintain yield.”

Fertilizer Canada is behind the 4R method and offers a stewardship program for farmers to adopt the framework and make a positive impact on the environment.

It’s not easy to strike a balance between reducing emissions, maintaining crop yields and costs.

“Change takes time,” said Clyde Graham, executive vice-president of Fertilizer Canada. “Farmers are doing quite well, generally. So you have to have greater incentives for them to make significant changes in operations.”

There is economic value in using the 4R principles, said Graham. According to Fertilizer Canada’s studies, Canadian farmers who used the 4R practices for nitrogen management saw an 18 to 29 per cent increase in profit per year, and an up to $87 per acre increase in profit.

“Essentially, farmers become more efficient in their fertilizer use, so they’re producing more crop for the same amount of fertilizer applied. At the same time, they’re reducing their N2O emissions.”

Another option is the rotation of crops, particularly with legumes, said Qualman. Legumes, with the proper soil bacteria, can convert nitrogen gas from the air to a plant-available form, meaning it does not need nitrogen fertilization.

“It’s about getting more nitrogen from biological sources rather than industrial sources,” said Qualman.

Ultimately, it’s a win-win, he explained. By effectively reducing the need for fertilizer, farm costs and N2O emissions can shrink.

Maavara, who is originally from Canada, spent years in southwestern Ontario interacting with farmers. She believes there’s a desire among farmers to change.

“We’ve already fertilized fields so extensively over the last 50 to 100 years that there’s already such a buildup of nitrate in the soils and the groundwater. Even if we went cold turkey right now and cut fertilizer use, we wouldn’t really start seeing changes for decades.”

Lessons from Europe

The study suggests lessons can be taken from Europe, where emissions have decreased over the past two years thanks to policies both in agriculture and industrial sectors to limit fertilizer and chemical use.

The European Union’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) is among multiple directives that helped guide sustainable farming and innovation.

“That was put in place more from a water quality standpoint, but it had the concurrent effect of reducing nitrous oxide emissions,” said Maavara. “A lot of it was incentivizing farmers to put in these best management practices.”

Brazil, China and India are “hotspots” for rising N2O emissions, but North America still ranks high on the scale.

In Canada, agriculture accounts for 10 per cent of greenhouse gas emissions overall, and N2O plays a big role in that, said Shane Moffatt, the head of Greenpeace Canada’s nature and food campaign.

Canada has committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 30 per cent of 2005 emissions by the year 2030, but Moffatt says more needs to be done. Greenpeace has been calling on Agriculture Minister Marie-Claude Bibeau to offer more supports and incentives to farmers to shift practices to “regenerative agriculture,” which is designed to reduce the use of synthetic fertilizers and increase biodiversity in soil to restore ecosystems.

“If the federal government wants to be serious about fighting climate change, ensuring food security, and supporting a green recovery from COVID-19 while hunger is on a rise, they need to put food and agriculture at the top of the agenda,” Moffatt said.

“Fertilizer use on Canadian farms is responsible for so much nitrous oxide that it accounted for nearly a quarter of total agriculture emissions in 2017 alone… By shifting farming we have enormous potential for both food security and climate mitigation.”

Ultimately, Maavara said their research signals the world is not on track to meet the Paris Agreement.

“I don’t want to say nail in the coffin, that’s a dark metaphor, but it’s definitely an alarming conclusion that indicates we need to be doing more if we want to keep under two degrees.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.