A report published in India in July revealed some worrying numbers on the prevalence of COVID-19 in some of Mumbai’s slums.

It estimated that around 57 per cent of people in three of the poorest areas of the city had been exposed to the virus, compared to just 16 per cent of Mumbai residents in non-slum areas.

More than half of Mumbai’s 12 million people live in crowded slums, which suggests a staggeringly high infection rate in the city, despite the number of deaths not appearing to match.

But like many COVID-19 statistics, it comes with caveats.

“The details matter,” said Canadian-Indian epidemiologist Prof. Prabhat Jha.

“If, for example, the assay (test) used wasn’t particularly good, then they might get a lot of false positives. So these details haven’t been released.”

However, the director of the Centre for Global Health Research says a similar study in Delhi suggested a similarly high level of infection, alongside a low death rate.

India and many developing countries have what appear to be low death rates from COVID-19.

The case fatality rate is the number of certified COVID-19 deaths compared with the number of confirmed cases of the virus.

Ten deaths among 100 confirmed cases would equate to a CFR of 10 per cent.

The actual death rate for COVID-19 (when including estimated numbers of unknown cases) — the infection fatality rate, or IFR – is thought to be under one per cent.

The worldwide CFR at the start of August 2020 is about 3.8 per cent.

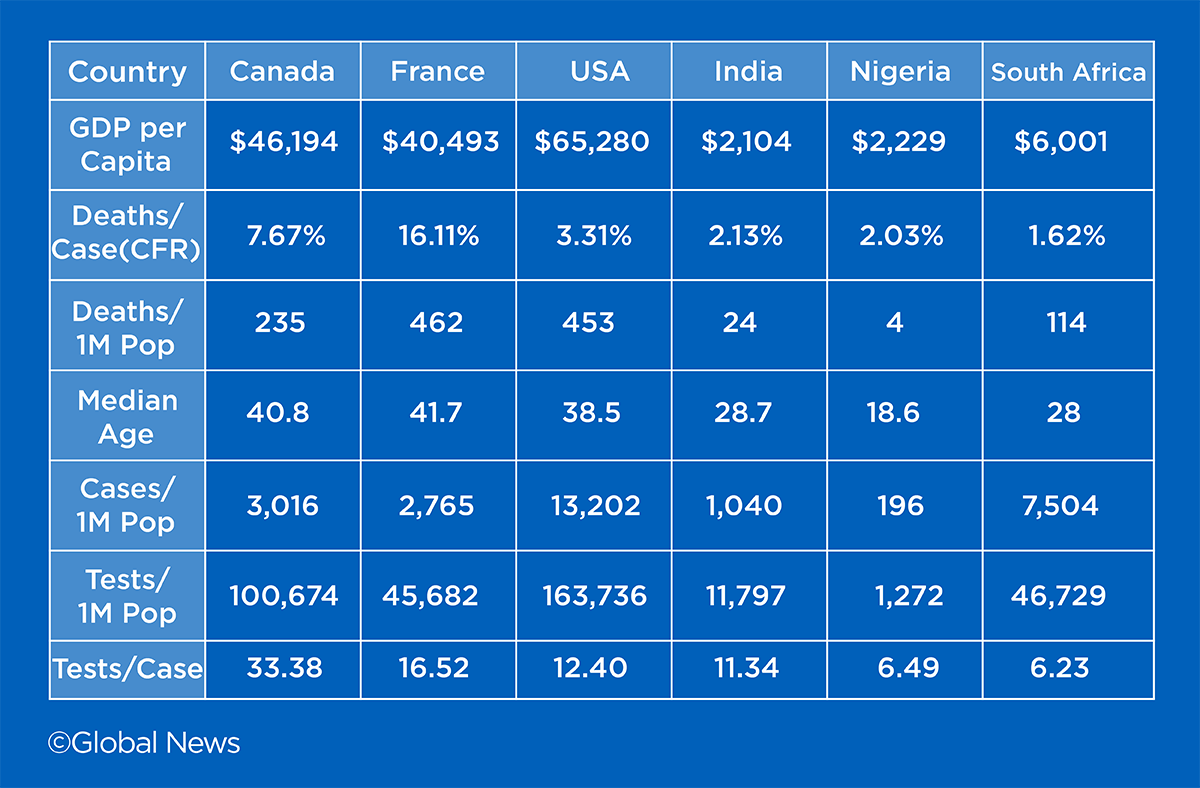

India’s CFR is just over two per cent, whereas the rate in Canada is about 7.67 per cent.

European countries like Italy, the U.K. and Belgium all have even higher CFRs. In France, it is above 16 per cent.

The Philippines, Pakistan, Nigeria and South Africa are all below three per cent.

There are exceptions — the United States is a relatively low 3.3 per cent, and some affluent Middle Eastern nations are lower still, whereas Mexico is 11 per cent.

However, the overall trend has experts looking in various places for answers, particularly when one might expect the health-care systems of poorer nations to be less able to treat seriously ill patients.

Does the CFR tell us that some populations are faring better than others?

Testing

Richer countries can afford to test more people, and will, therefore, find more positive cases — just ask U.S. President Donald Trump.

At the start of August 2020, U.S. authorities had carried out almost 60 million tests and had identified 4.7 million cases.

In countries with fewer resources, like South Africa, health-care systems are forced to prioritise who they test.

“Unfortunately, due to the global demand, particularly for test reagents, we haven’t been able to meet to our full testing capacity,” said Mary-Ann Davies, director of the Centre for Infectious Disease Epidemiology and Research at the University of Cape Town.

“In Cape Town, in particular, because we faced the surge in infections the first, we had to restrict our testing to people who were over the age of 55, or had comorbidities (other diseases), in whom it was more important to get a diagnosis.”

Get weekly health news

In Nigeria, the level of testing is even lower, where fewer than 300,000 tests have been carried out in a population of more than 200 million.

“I think the challenge goes back to infrastructure,” said Prof. John Nwangwu a Nigerian-American epidemiologist and public health doctor at Southern Connecticut State University.

“The infrastructure here includes the set-up of the health care system, how things flow, the resources to be able to do the testing and tracing. I think it’s a challenge specifically in Nigeria.”

Of course, if you do the math, a lower number of tests (and identified cases) should theoretically mean a higher CFR in poorer countries, not a lower CFR.

That suggests the number of deaths attributed to COVID-19 is being hugely underestimated in parts of the developing world.

It’s also why Jha warns against placing too much weight on the CFR.

Counting deaths

Counting deaths should be easier than counting cases, but that’s not necessarily the case.

“Seventy per cent of deaths in India occur in the rural areas, and 70 per cent don’t have any certification, they don’t have a death certificate,” said Jha, who led the Million Death Study in India, a project which helped better-estimate the causes of premature deaths across the sub-continent.

Jha says similar measures are needed to find out just how many people in India are dying from COVID-19.

“This is urgently needed because we might have a hidden epidemic of elderly people in rural areas dying from COVID that are just missed because of the lack of death certification.”

Jha notes larger cities like Mumbai are reporting higher death rates than rural areas.

But even in countries where causes of death are fully monitored, data suggest the official numbers are still too low.

“Excess deaths” is a number that compares the total number of deaths in a given time period with the expected number of deaths based on previous years.

Analyses carried out by the Financial Times and the New York Times, indicate that many countries — rich and poor — have significantly underestimated COVID-19 deaths.

“Even in wealthy countries, we have seen this discrepancy between COVID deaths and other excess deaths,” said Davies.

“And I think even in those countries, we’ve seen sudden spikes in the number of deaths reported on one day, which suggests that there are challenges with counting deaths.”

Because baseline historical death data is unreliable in countries like India, accurately estimating excess deaths can often be extremely difficult.

Nwangwu says one of his relatives in Nigeria — who he believes died from COVID-19 — did not have the virus mentioned on their death certificate.

The data sources used for counting COVID deaths vary considerably across the world, with some countries including care home deaths, and others, like Belgium, including suspected COVID deaths, too.

Younger populations

Experts generally agree the developing world has a distinct advantage when it comes to age profile.

Older people are far more likely to die from COVID-19, whereas children rarely suffer serious symptoms.

Canada’s median age is just above 40, a similar number to most western nations.

Median age means half the population is below that age and half is above.

India is 28.7, South Africa 28.0, Nigeria is just 18.6.

“The average age of India is way lower than, let’s say, in Europe or in Canada,” said Jha.

“And as we already know, worldwide COVID hospitalisations and deaths tend to occur in the elderly and those with existing chronic diseases. So in India, the younger age distribution might be a factor.”

Care home culture

Western nations like Canada have a higher prevalence of older people living in long-term care facilities, whereas in the developing world, seniors are far more likely to live with their children and grandchildren.

A Canadian Institute for Health Information study in June found that 81 per cent of Canadian COVID-19 deaths occurred in long-term care facilities, which was about twice the average rate from other developed nations.

Jha believes this could be a factor in explaining why developing nations like India have a lower apparent death rate, but he also pointed out that seniors in India could have been placed at risk by the nature of India’s sudden national lockdown in March.

“Many urban men, in particular, were kicked out of their homes and told to go back to their villages,” he said.

Earlier in the curve

The major air transport links between richer countries could also be a factor.

The virus’s epicentre moved from China to Europe, and on to the United States in the early months of the pandemic.

It may have given less-connected countries time to react and flatten their curve before the virus took hold, but now that countries have partially eased their lockdowns, it could be a case of delaying the inevitable.

“The trajectory of the epidemic is a slow time-bomb. You see a slow growth, but you see growth. And that’s the main concern,” said Jha.

“And if the Indian pandemic goes right through to November, December, the economic disruption, the disruption in terms of reopening schools or others would be of real concern.”

Nwangwu, who conducted investigation work and disease control for Ebola in West Africa, says it appears the virus’s spread is gaining speed in Nigeria.

“I am in touch with some of my friends and some extended relatives who keep complaining to me about people dying, and that the infection is picking up steam, you know, in a slow process,” he said.

“There’s no question that it is a silent killer.”

On July 20, Michael Ryan, the head of the WHO’s emergencies programme, warned about what could be coming across the continent of Africa.

“I am very concerned right now that we are beginning to see an acceleration of disease in Africa, and we need to take that very seriously,” said Ryan.

Exposure to other diseases

Are we just softer in the West?

There is not much hard evidence on this front, but there are theories that exposure to viruses and other diseases in developing countries could help the populations’ immunity.

“This sort of ‘hygiene hypothesis,’ that countries that have worse general infectious disease burden, may perhaps have some cross-immunity that makes them less susceptible to COVID-19.”

Davies says one distinct advantage South Africa has had is the infrastructure put in place to deal with its high prevalence of HIV infection.

“The testing platform for COVID, it is the same. The PCR (polymerase chain reaction) platform. So actually our laboratories were well-placed to roll out the tests. The challenge was just with accessing reagents and testing kits. So in other countries that don’t have as good laboratory capacity, that would be challenging.”

There are also studies underway to see if the Bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccine — widely used in Africa to fight tuberculosis — could protect against COVID-19.

BCG injections are mandatory at birth in South Africa.

The vaccine is no longer widely administered in Canada, apart from on First Nation reserves and in Inuit communities.

Different measurements

Jha says, rather than refer to the CFR, he prefers using the overall death rate as an indication of how a country is dealing with the pandemic.

That figure is simply the number of COVID-19 deaths per capita, rather than per confirmed test.

“The more reliable statistic is not the testing rate because that varies. Either the very healthy or the very sick get tested. But the death rates are actually a very good indicator of the trajectory of the epidemic,” said Jha, noting that the overall deaths per capita in India is still quite low.

“In India … the overall death rate is about 27 per million from COVID, and that’s a tenth of the Canadian rate.”

Jha and other experts agree that if governments can’t accurately track how the virus is spreading, then they can’t effectively tackle it.

“The only way for India to walk out of this pandemic will be with much better data,” he said.

“Governments, like people, get scared, with releasing data that they think will frighten people with too much information, but that’s actually the opposite. Better data give you a handle on whether you are.”

Comments