On March 3, British Prime Minister Boris Johnson fatefully implied that close contact with COVID-19 patients was nothing to worry about.

“I was at a hospital the other night where I think there were actually a few coronavirus patients,” he said, eight days before the World Health Organization characterized COVID-19 as a pandemic.

“And I shook hands with everybody.”

Johnson rolled back his comments a few days later, but it was one of a series of instances where the U.K. government was accused of issuing mixed messaging during the pandemic.

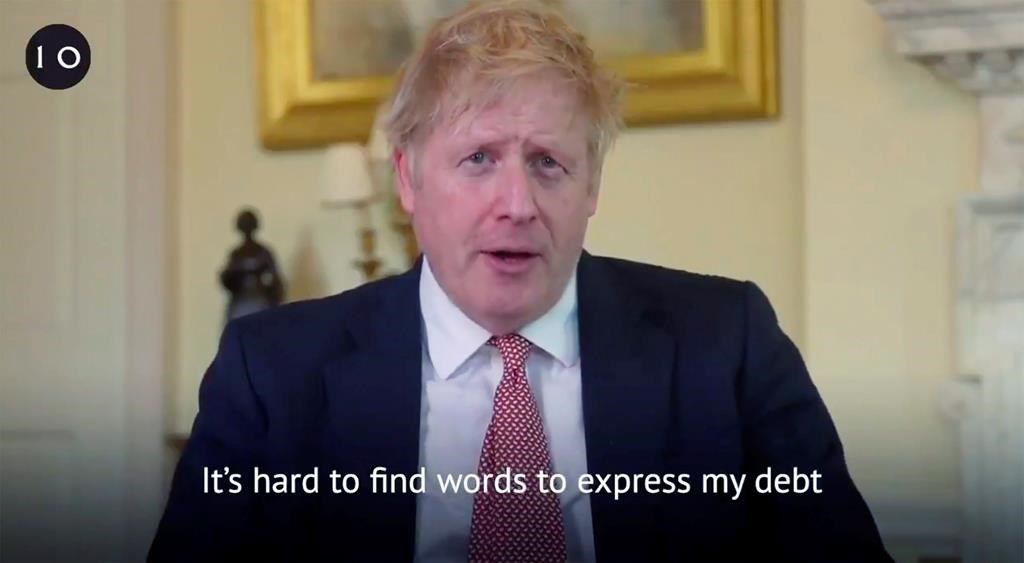

By the end of March, Johnson and his health secretary, Matt Hancock, had both contracted the virus.

Johnson almost died in intensive care, later telling the British public, his situation “could have gone either way.”

Contracting the virus may not have been his fault, but it wasn’t a good look for a leader already under fire for dithering as the pandemic swept across Britain.

Perception of his leadership was hit again when his chief adviser, Dominic Cummings, was accused of breaking rules by driving 400 kilometres during the lockdown while Cummings’ wife showed COVID-19 symptoms.

Cummings stayed in his job, whereas north of the border, Scotland’s chief medical officer resigned after a similar controversy.

Throughout the COVID-19 crisis, the devolved governments in the U.K.’s three smaller nations have been managing the pandemic in Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales.

They, along with England, entered lockdown together, but as the months passed, they have asserted their own powers more and more by diverging from London’s strategy.

Scotland and Wales, in particular, have been slower to reopen their economies as the lockdowns have eased.

Get weekly health news

Sturgeon’s surge in support

- Carney says former prince Andrew should be removed from line to throne

- LeBlanc says U.S. meeting on CUSMA and trade ‘constructive and substantive’

- Ottawa, Alberta reach prospective agreement on major project assessments

- ‘A foreign policy based on short memory’: Carney continues push to diversify from the U.S.

Leaders in Wales, and particularly Scotland, have shown increasing impatience with decisions made in London that have impacts across the four U.K. nations.

”When so much is at stake, as it is right now, we can’t allow ourselves to be dragged along in the wake of another government’s — to be quite frank about it — shambolic decision-making process,” said Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon on July 3, responding to proposed U.K. government rules on international travel.

“We’ve often had limited or no notice of the U.K.’s proposals, and that matters because some of the judgments involved here are difficult and complex.”

Sturgeon — leader of the pro-independence Scottish National Party — has been praised for her no-nonsense approach to the pandemic.

It’s been accompanied by strong polling numbers for her and her party, which would theoretically translate into a big majority in next year’s Scottish elections.

The first half of this year has also seen strong and sustained support for Scottish independence in numbers not seen since the 2014 referendum, when 55.3 per cent of Scots voted to stay in the U.K.

“It looks as though, probably, there is a small majority in favour of independence,” said Sir John Curtice, professor of politics at the University of Strathclyde in Glasgow.

“That increasing support has occurred in two stages. Much of it was in evidence last year before anybody heard the word ‘coronavirus,’ and that was clearly linked to the debate about Brexit.”

Curtice says the second jump in support for independence has come this year, from voters who were on both sides of the Brexit referendum — where Scots voted by 62 per cent in 2016 to remain in the European Union.

“What we do know from more than one poll is that the Scottish public thinks that Nicola Sturgeon has handled the coronavirus well, very well indeed,” said Curtice.

“And they think that Boris Johnson has not done terribly well at all.”

One poll in May showed just 30 per cent of Scots approved of Johnson’s performance during the crisis, compared with an 82 per cent approval for Sturgeon.

No English, please!

As of mid-July 2020, the U.K. remains the European country with the highest number of COVID-19 deaths; the vast majority of those have been in England (where 84 per cent of the U.K. population lives).

Scotland’s and Wales’ death rates per capita are about a third lower than England’s.

“We’re pretty confident that Scotland was at least a week behind London, if not more, in terms of how cases came north of the border (from England). And that means that when we implemented lockdowns in the U.K., which was across the U.K. at the same time, we had fewer cases,” said Linda Bauld, a Scottish-Canadian professor of public health at the University of Edinburgh.

Bauld says the ability of the devolved Scottish government to manage its own health policy — rather than rely on London — has been illustrated by the different strategies pursued north and south of the border.

The case numbers in England have also sparked a new type of protectionist nationalism among some Scots.

“So when then criticism of people coming (to visit) from England into Scotland has come to the fore, you have seen members of the community trying to stop cars from coming up the A1, which is the main trajectory highway into Scotland, and putting up signs saying ‘you’re not wanted here, English, please go away,'” said Bauld.

Curtice says the crisis has also brought a new awareness of the realities of devolution, particularly to English people.

“(It was) the fact that you could go to the beach in England but could not go to the beach in Scotland for a while,” said Curtice.

“The pubs were open in England, but they were still not open here. These are things of which the public across the U.K. became aware of.”

The unity of the United Kingdom will be tested by this new awareness in the years to come.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.