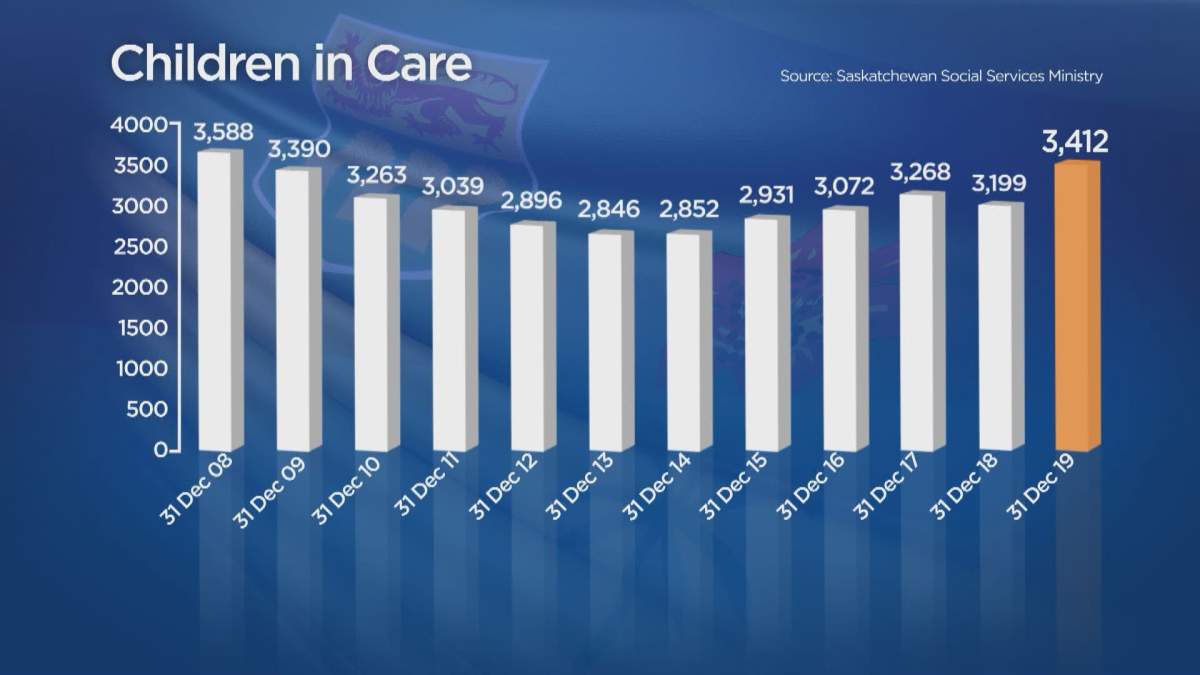

The number of children in Saskatchewan’s care last year was the highest it’s been in over a decade, with a huge proportion of those children identified as Indigenous.

Global News has learned there were 3,412 children in the province’s care in 2019, according to Ministry of Social Services data. It’s the largest number the province’s child welfare system has seen since 2008, when there were 3,588 children in care.

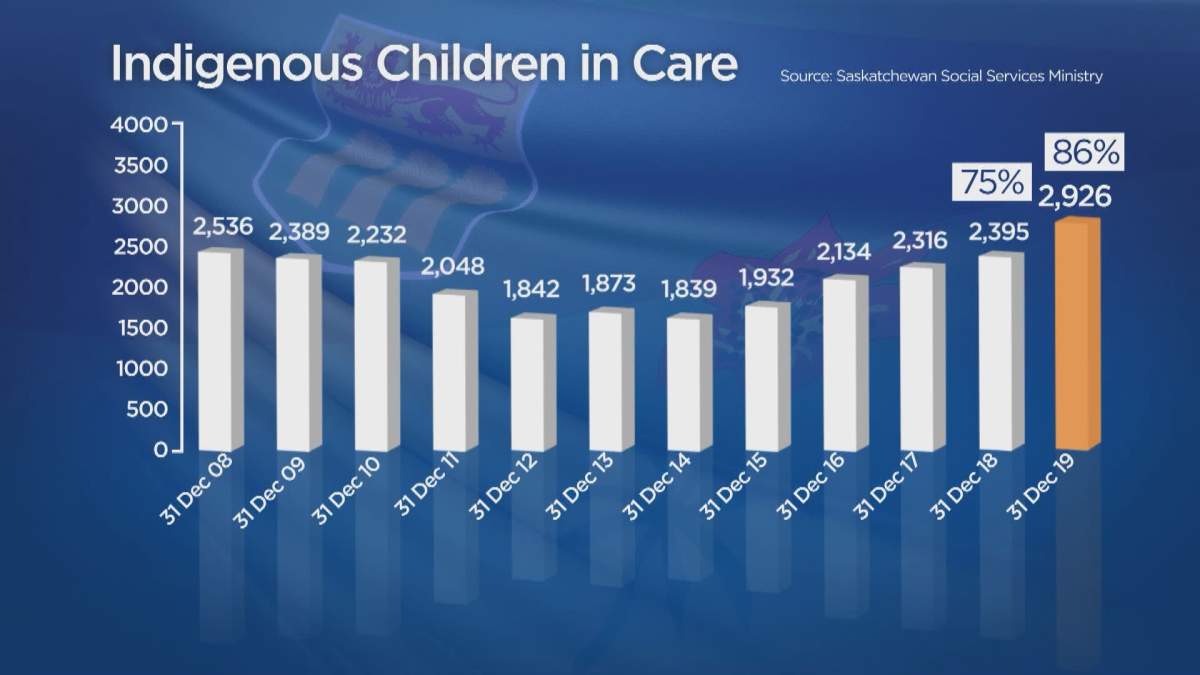

The already disproportionate number of Indigenous children in the system is significantly higher than previously reported. About 86 per cent (2,926) of children in care last year were identified as Indigenous, up from 75 per cent (2,395) in 2018.

That number is expected to continue to climb due to better reporting, the Social Services Ministry said.

“That is a basic right for Indigenous children — to be identified formally in membership to their Indigenous community,” said Janice Colquhoun, executive director of Indigenous services for the ministry’s child and family program.

“It’s part of the foundation of their cultural and roots alignment and identity to their community.”

Child protection services are working with families and band registration personnel to ensure more First Nations, Métis and Inuit children are properly identified, Colquhoun said.

Get breaking National news

Saskatchewan’s advocate for children and youth, Lisa Broda, said the number of Indigenous children in care is — and always has been — an egregious outcome of Canada’s colonial history.

“We all know that the numbers are high and disproportionate, and there has been a gross and persistent over-representation of Indigenous children in care,” Broda told Global News.

“It’s been decades, and our system isn’t working for Indigenous children.”

Colquhoun said the ministry has received $3 million in the last two budget years to partner with Indigenous organizations and develop initiatives to keep families together.

“The increase of children in the past year was a disappointing development for us, given all of the initiatives and work going on,” she said, noting that apprehension is a last resort.

“There continue to be some forces out there in the community that are a challenge for everyone to deal with, but we hope that we can continue to get the pathway down for having children coming into care.”

Addressing the systemic problems that contribute to child apprehension — namely intergenerational trauma, mental health, addiction and poverty — is key to keeping Indigenous children with Indigenous families, Broda said.

“What we’re doing now isn’t working,” she said. “We’re reacting and we need to be proactive.”

The provincial and federal governments are obligated to uphold the health, social and economic rights of children, as per the UN’s Convention on the Rights of the Child, Broda added.

More funding, partnership and policies should be targeted at upholding those rights, she said.

The federal government took a step in that direction with its Act respecting First Nations, Inuit and Métis children, youth and families, which came into force on Jan. 1.

The law empowers Indigenous communities to reassert their jurisdiction over child welfare.

Cowessess First Nation in southeast Saskatchewan ratified its own Child and Family Services Act in March, becoming the first Indigenous community in Canada to do so.

Cowessess First Nation Chief Cadmus Delorme said the number of children in care is alarming but not surprising.

“One child in care is too much. And to have the percentage that high, … it just shows how much work we all have to do,” Delorme said.

“It all stems back to what we all inherited.”

Retaking control of child and family services will give Cowessess the final say on whether children stay with their families, instead of leaving it up to a judge or the Social Services Ministry.

“It just puts Cowessess back in the driver’s seat, whereas before, we were in the passenger’s seat as our children were being dealt with,” Delorme said.

“The best interest of the child is not based on a political position. It’s based on someone with the capability to understand the situation.”

Cowessess is working on a co-ordination and funding agreement with the provincial and federal governments, which Delorme said have been supportive.

“We’re in this for healing,” he said. “Within 50 years, Cowessess shouldn’t have any children in care.”

Comments