The Ontario government on Monday was the latest province to outline its COVID-19 economic recovery plan, but when compared to other provinces’ plans released last week, Ontario’s was starkly different for one reason: it wasn’t anchored to any specific dates.

But that’s not a bad thing — rather, it’s “encouraging,” public health experts say.

“To me, it makes more sense to not have dates,” said Craig Jenne, an infectious disease expert and associate professor at the University of Calgary.

“I do understand some provinces are able to put out dates because they may be actually at the point now where it is time for them to start reopening.

Premier Doug Ford and several cabinet ministers on Monday released what they’re calling a “framework” for re-opening Ontario’s economy. The government is hearing from experts now that the province is in the “peak” of the novel coronavirus outbreak, Ford said during a press conference at Queen’s Park.

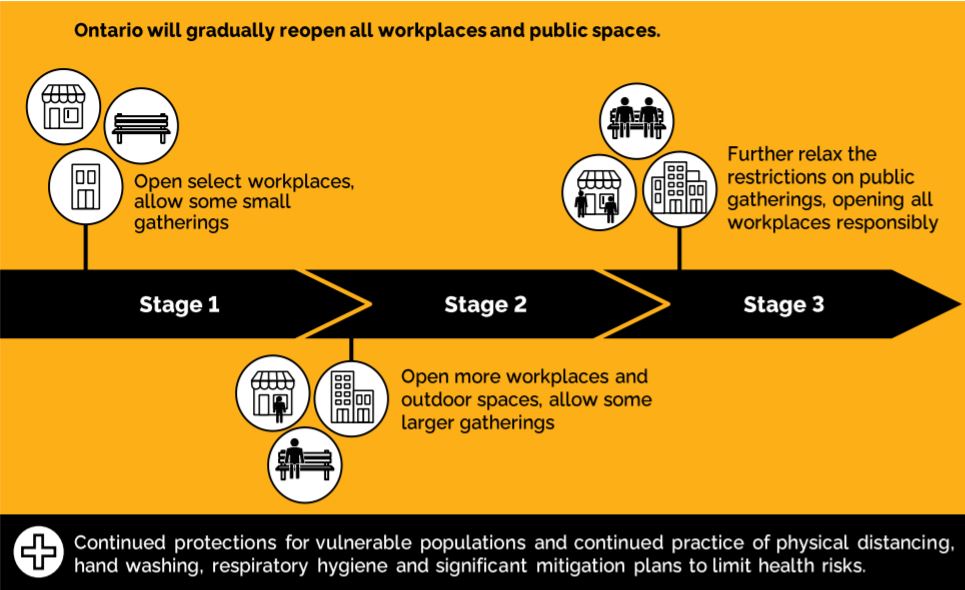

Unlike the recovery plans other provinces have announced so far, the Ontario government’s three-phrase approach didn’t include concrete dates for when the easing of public health restrictions would begin. Rather, Ontario’s framework outlined factors officials will consider before kick-starting the province’s recovery process and moving from one stage to the next.

Those criteria include high levels of testing, conducting 90 per cent of contact tracing for new cases within a day, sufficient access to ventilators and personal protective equipment and “a consistent two-to-four week decrease in the number of new daily COVID‑19 cases.”

“This is a road map. It’s not a calendar,” Ford said.

Even without any concrete dates in the mix, Winnipeg-based epidemiologist Cynthia Carr said the framework demonstrates provincial leaders “have given thought to what they need to have in place for this to be most successful.”

“The reason they’re not putting data is probably they want to make sure that they absolutely have these resources … before they start opening it up,” said Carr, owner and principal consultant at EPI Research Inc. “Otherwise … they can’t stick with what they said they were going to do.

“The worst thing would be to give a date and then people get excited and antsy, because we know uncertainty is one of the worst things about this situation.”

Once it has implemented a new stage, the provincial government said it will take between two and four weeks to monitor “any impacts or potential resurgence of cases.”

Get weekly health news

Asked whether that’s enough time to review what the virus is doing in the community and make well-informed decisions, Carr and Jenne noted that a two-week period has its limitations because of the virus’ 10-day incubation period.

“If you had some viral spread at the end of the first week or first 10 days of relaxing phase one, those patients may not even appear in the medical system until you’ve surpassed that two to three week time point and then you’re basing a decision without a complete dataset,” Jenne said.

As part of Ontario’s criteria for moving forward, Carr suggested that officials also take into account declines in coronavirus-related hospitalizations and deaths — not just a decline in new cases — because the public health system might in fact detect more cases in the push to ramp up testing and contact tracing.

“We don’t want to see a change in patterns. We don’t want to see a whole bunch of new symptomatic cases in certain age groups that we didn’t anticipate,” she said.

Both Carr and Jenne agreed that Ontario will have to offer more details and clarify who gets to do what during each stage of the plan, noting those specifications were missing from the document released Monday.

Provinces already taking similar approaches, experts say

The release of Ontario’s framework on Monday comes after Saskatchewan, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island announced their first steps down the path to pandemic recovery last week.

For its part, New Brunswick announced its recovery plans would begin immediately while Saskatchewan and P.E.I. said they would begin to loosen restrictions in early May.

The release of these plans come as Prime Minister Justin Trudeau says his government is still working with the provinces and territories on a list of a “shared guidelines” for easing public health restrictions, in order to ensure “clear, coordinated efforts” as they work to re-open Canada’s economy.

Those “shared guidelines” haven’t yet been announced, but experts say there’s already some “consistency” and common ground in the provinces’ approaches so far.

For instance, they’re first loosening restrictions on using outdoor spaces and partaking in outdoor activities, letting select businesses unlock their doors and reopening certain aspects of the health care system, Carr and Jenne noted.

But Jenne said a national strategy still has its merits.

“We do not want mixed messages where you’re allowed to do one thing and something completely different in another province,” he said.

“We do still travel in this country. We still go from province to province. And as we open up, that’s going to happen more.”

Asked about how provinces are communicating the size of gatherings that are permitted — New Brunswick, for example, is proposing “two-household bubbles” while others just set a maximum number of individuals — Jenne said the restrictions are “essentially the same thing” but a “universal dialogue” might help avoid confusion.

Ontario and Quebec together account for more than 80 per cent of the more than 48,000 cases of COVID-19 in the country.

Quebec, however, does appears to be taking a different approach from the others, announcing on Monday afternoon its plan to gradually reopen elementary schools and daycares in May.

For comparison, Ontario extended its school closures until May 31 and Saskatchewan’s premier said that province won’t broach the topic of reopening schools at least for several more weeks.

Trudeau told reporters on Monday that provincial and territorial plans don’t need Ottawa’s blessing, as most measures fall outside federal jurisdiction.

“They have the responsibility to do what is right for their citizens,” he said Monday.

“I have full confidence in the premiers of the provinces and the territories to move forward in a way that is right for them.”

As of mid-day Monday, there were 47,316 confirmed COVID-19 cases across Canada, including 2,617 deaths and 17,929 resolved.

— With files from Kalina Laframboise and The Canadian Press

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.