The Indigenization of Canada’s prison population is nothing short of a national travesty, says Ivan Zinger, the correctional investigator of Canada.

Last month, Zinger issued a report indicating Indigenous people are being imprisoned at a historic rate despite there being an overall decline in inmate populations.

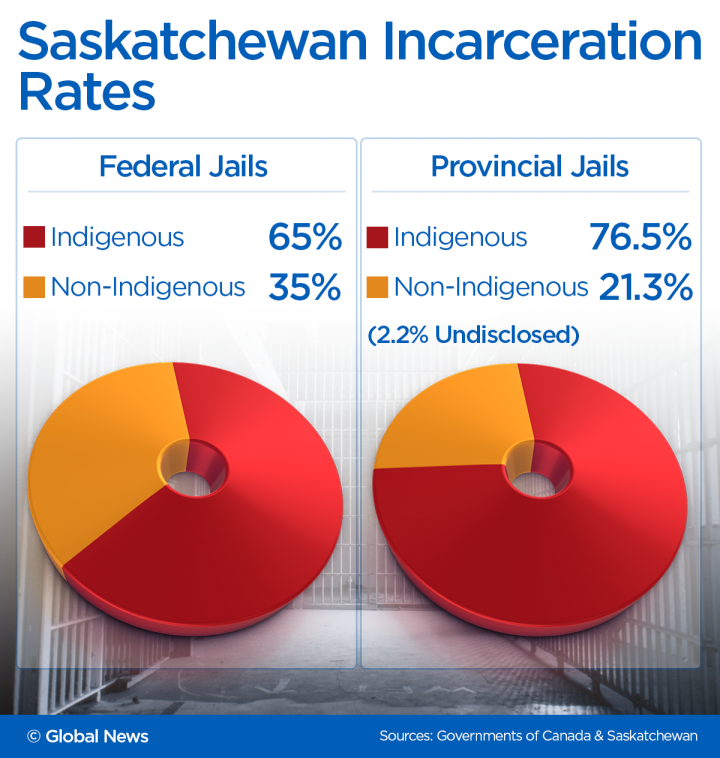

In Saskatchewan, Indigenous people account for 65 per cent of the total prison population federally, which is twice as much as the national average of 30 per cent.

In provincial jails, Indigenous offenders make up 75 per cent of the population. The government of Saskatchewan said this number has been consistent for the past five years.

“No government of any stripe has managed to reverse the trend of Indigenous over-representation in Canadian jails and prisons,” Zinger said.

The correctional investigator said a “bold and urgent action is required to address one of Canada’s most persistent and pressing human rights issue” as efforts to curb over-representation is not working.

- Canadian immigration officers investigating hundreds identified by extortion task force

- Carney unveils ‘Buy Canadian’ defence plan, says security can’t be a ‘hostage’

- Inflation cooled to 2.3% in January but food prices up again: StatCan

- Ottawa expects Ukrainian emergency visa holders to return after war ends

In the mid-90s, Gladue factors were put into place to reduce the misrepresentation of Indigenous people in the prison system.

Get daily National news

“What we’ve seen then is the numbers have doubled, tripled and for women quadrupled,” said Senator Kim Pate, a former Saskatchewan lawyer and former head of the Canadian Association of Elizabeth Fry Societies.

“So the reality is they’re not being taken into the way they should be, and too often — particularly in Saskatchewan — it’s lip service.”

Harold Johnson, an Indigenous lawyer, who served as a Crown prosecutor in Saskatchewan for 10 years said there needs to be an overhaul of the criminal justice system.

“We’re relying on an idea that doesn’t work,” Harold said. “Many recognize what we’re doing is worse, but no one can imagine doing anything different.”

In his book Peace and Good Order, Harold recommends eliminating the principle of deterrence from the Criminal Code and replacing it with redemption.

“Let people earn their way back into society. Quit trying to punish people — it doesn’t work,” Harold said.

Pate agreed that a new approach must be taken in order for things to change.

“There’s a lot we should be doing beforehand that would benefit those who are in prison and are in our communities,” Pate said. “Those who are struggling because they’re poor because they have mental health issues because they don’t have jobs – all of the things we know we need to work on.”

She said the roadmaps to change the criminal justice system have been laid out already by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s Call to Action, First Nations Child and Family Caring Society and the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal.

“What we really need to be doing is implementing those calls to action, and calls for justice,” Pate said.

“I think we’d go a long ways.”

Comments

Comments closed.

Due to the sensitive and/or legal subject matter of some of the content on globalnews.ca, we reserve the ability to disable comments from time to time.

Please see our Commenting Policy for more.