Anthrax is best known as a biological weapon but this week, it was identified as the cause of death for seven farm animals in Saskatchewan.

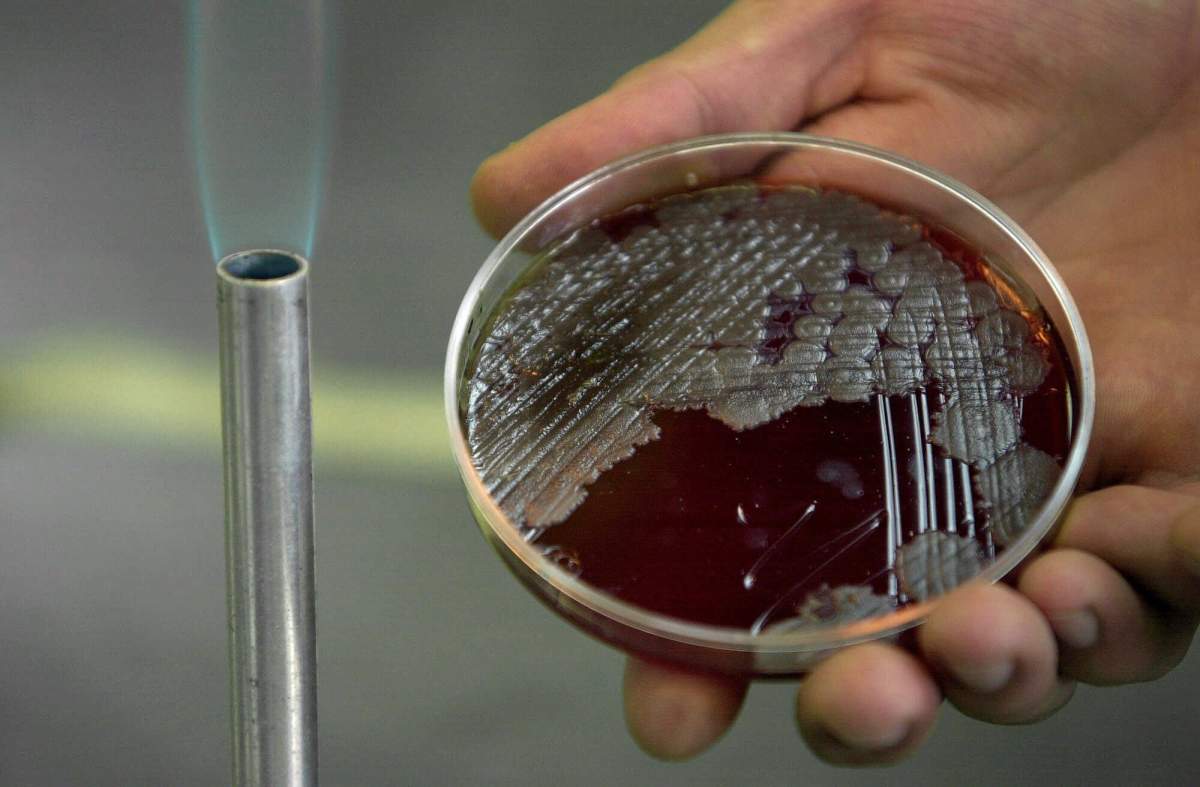

The presence of anthrax, which occurs naturally, was confirmed through laboratory testing on the deceased livestock.

While such cases are uncommon in Canada, here’s a closer look at the illness, and the threat it poses to wildlife.

What is anthrax and where is it found?

Anthrax is the name of the disease caused by infection from Bacillus anthracis spores, which are present worldwide.

The illness can have “devastating effects” on grazing animals such as cattle, bison, sheep, horses and goats, according to the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA).

It may have originated in ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says, and is believed to have been depicted in the writings of Virgil and Homer.

Anthrax cases have occurred from Alberta to western Ontario, the CFIA says. There have been several outbreaks in the Mackenzie Bison Range in the Northwest Territories and Alberta’s Wood Buffalo National Park.

Though anthrax typically affects animals grazing on prairies, Winnipeg’s Assiniboine Park Zoo suffered an outbreak in 1998 that killed several bison and white-tailed deer. Anthrax also was responsible for the deaths of 13 bison on a farm in Fort St. John, B.C., last year, which the Canadian Press reported was the province’s first documented case.

The livestock that died in the Rural Municipality of Chester, Sask., represented the province’s first animal anthrax fatalities since 2015, said Dr. Wendy Wilkins, disease surveillance veterinarian with the province’s Ministry of Agriculture.

WATCH: Dozens of pigs on the loose near Vermont town

The Saskatchewan government is withholding the name of the species affected to protect the producer’s privacy. Wilkins said the animals were not cattle but fell under the category of ruminants, a group that includes cattle, sheep, goats and some other animals.

How big of a threat does anthrax pose to livestock and people?

Get daily National news

Dr. Luis Arroyo, a Guelph, Ont., veterinary professor who specializes in large animal internal medicine, explained that the risk of anthrax in northern countries like Canada is low — it’s more prevalent in tropical regions.

“I’ve been here at the Ontario Veterinary College for 20 years, 19 (years), and I’ve never seen a case,” he said.

Wilkins said anthrax found in soil is considered “very low” risk for people.

“Domestic animals seem to be more susceptible than people — they also act as multipliers, though,” she said. “So, although the anthrax in the soil might not affect people, it gets into the animals. Then, if you’re exposed to the animals, you also are at risk for anthrax.”

According to the BC Centre for Disease Control, 95 per cent of the human cases of anthrax around the world are contracted through the skin, though it can also affect the lungs or digestive system.

WATCH: Bison free-roaming Banff National Park’s backcountry

In those cases, the disease can show up within a day or a week of exposure to an infected animal, and starts as a small bump on the skin that “turns into an open wound with a black centre.”

The illness is treated with antibiotics.

The anthrax spread by animals is less potent than the substance used as a biological weapon in attacks such as one in the U.S. in 2001 that killed five people.

How does infection occur?

Livestock or wild animals such as bison are most commonly infected by eating contaminated pasture, feed or soil, according to the CFIA.

Wilkins said the bacteria that causes anthrax is very hardy and can stay in soil for 40 years or longer.

“We have conditions where it may flood and the bacteria are brought to the surface, moved into a low-lying area and there they accumulate,” she said. “Then we have a dry summer, like we did this spring and early summer, potholes dry up, the animals get in there, they get anthrax.”

WATCH: New feed-testing tools aim to help cattle welfare in Alberta

The bacteria don’t reproduce well in the air, Arroyo said, and not all strains are virulent, but when the perfect storm of conditions is met, an animal’s death can come quickly.

“The infection is very acute,” Arroyo said. “Some animals will die with almost no clinical signs, it’s so fast.”

Others, he added, might demonstrate a fever before suddenly dying.

From there, the disease has the potential to spread to other animals and surroundings. The spores can enter the human body through inhalation, wounds and mucous membranes such as the mouth, the CFIA says.

Producers and labs are required by law to report suspected anthrax cases to the CFIA. And care has to be taken to prevent the further spread of the illness in disposing of the remains.

WATCH: Dry conditions lead to concern for grazing cattle

In Saskatchewan, Wilkins said the response includes a government vet working with the producer to see that other animals are removed from the contaminated pasture if possible, and taking steps to ensure they are protected through treatment or vaccination.

Wilkins suggested producers in the area affected by the Saskatchewan outbreak vaccinate their herds.

“Anthrax is often isolated just to a single source but we cannot predict it and vaccination is the best protection,” she said.

With files from Global News Regina

Comments