The details of Ottawa‘s new First-Time Home Buyer Incentive (FTHBI) are finally out, and the question for any Canadian struggling to afford their first home is: is it a good deal?

Under the program, which was first announced in the federal budget in March, the government is offering an interest-free loan to help homebuyers take out a smaller mortgage and keep monthly repayments lower. New information released on Monday clarified that, when the loan is repaid, the government will also get a share of any gains from the appreciation of the property.

Vice versa, if the value of the home has dropped, Ottawa will shoulder a percentage of the loss.

The measure will reduce monthly mortgage costs by up to $286 and is expected to help some 100,000 families become homeowners, Jean-Yves Duclos, minister of families, children and social development, said in a prepared statement.

Sources consulted by Global News, though, had either negative or mixed reviews of the proposed incentive. Here’s what you should know:

Qualifying for the incentive

In order to participate in the FTHBI, you must meet two main requirements: be a first-time homebuyer and have an annual income of no more than $120,000.

The government sets out the criteria for who can call themselves a first-time buyer, a definition that is more nuanced than one might think. The income test is subject to requirements set out by lenders and mortgage loan insurers.

Buyers must come up with their own cash for a down payment of at least five per cent of the property value, but the incentive is meant only for mortgages greater than 80 per cent of the home value. In other words, if you’re planning on a down payment of 20 per cent or more, this isn’t for you.

The maximum home price you can aim for is four times your income plus the incentive amount.

WATCH: By the numbers — renting vs. owning

How the math works*

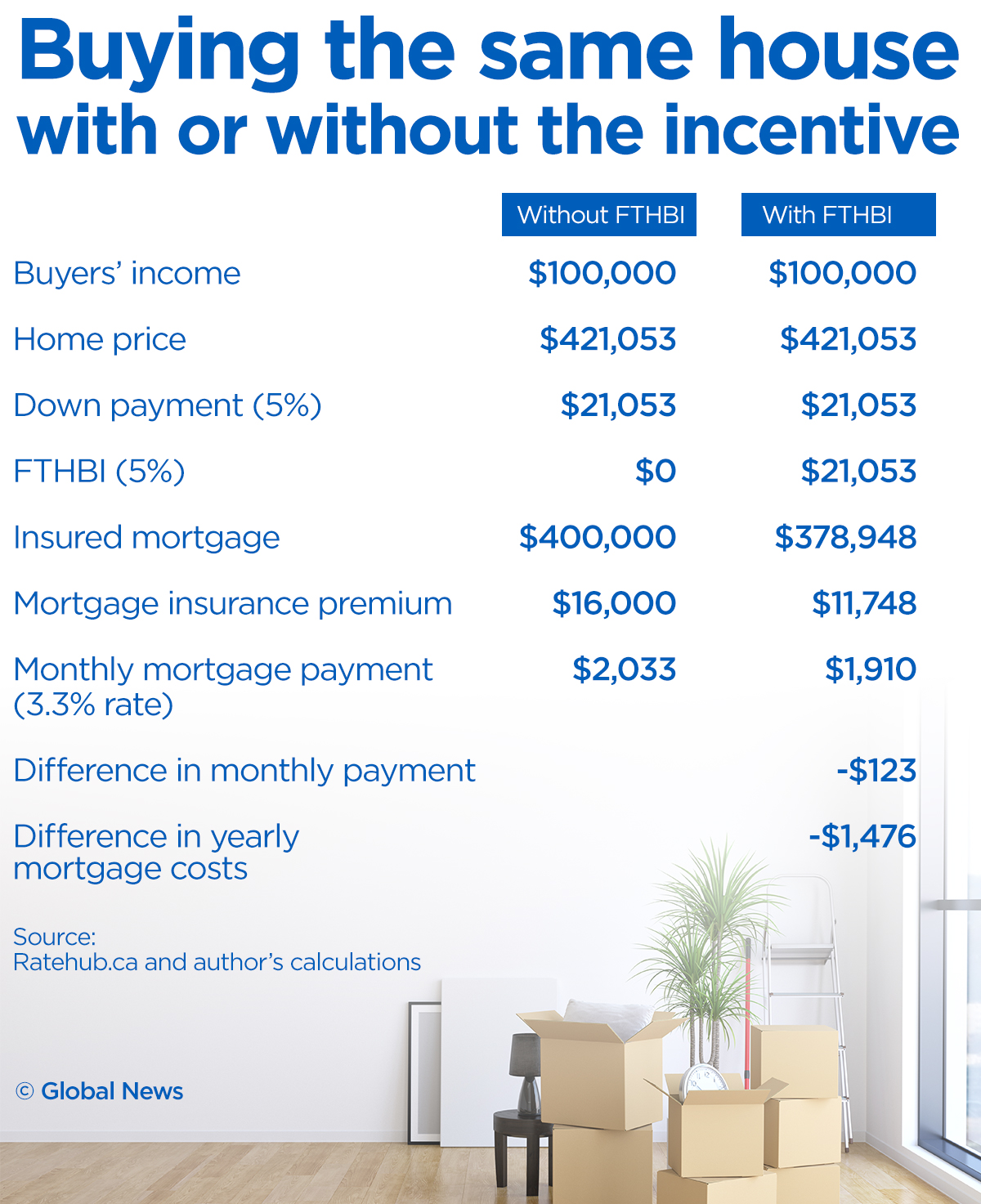

Let’s say your annual income is $100,000, comfortably under the government’s $120,000 cap. According to calculations provided by rate-comparison site Ratehub.ca, the most expensive home you could hope to buy with the incentive would be worth $421,053.

For a five per cent down payment, you’d have to have around $21,000 in cash at hand. Assuming you were buying an existing home, the available five per cent FTHBI would provide another $21,053. Your mortgage would be $378,948 ($421,053 – ($21,053*2)), smaller than the $400,000 it would have been without the government top-up. This will also reduce the amount of your mortgage insurance premium, which works out to $11,748 in our example.

- WestJet execs tried cramped seats on flight weeks before viral video sparked backlash

- Pizza wars? As U.S. chains fight for consumers, how things slice up here

- Health Canada says fake Viagra, Cialis likely sold in multiple Ontario cities

- Canada increased imports from the U.S. in October, StatCan says

Thanks to the smaller mortgage and insurance premium, your monthly mortgage payment would be $1,910, instead of $2,033 you would have had to pay without the incentive. That’s a difference of $123 a month, or $1,476 a year.

The incentive would be a second mortgage on the title of the property. The loan has no interest nor regular principal payments. You must repay the loan after 25 years or when you sell the house, whichever comes first. You can also repay the loan at any point before that with no penalty.

The catch, though, is that if your home has appreciated at the time of repayment, the government gets a share of the gain. In our example, let’s say you decide to sell after a few years when the home price has risen 10 per cent to $463,158. You’d have to pay five per cent of that, or $23,158, to the government.

Get weekly money news

If the home value had dropped 10 per cent, you’d get to repay 10 per cent less of what Ottawa originally lent you, or $18,948.

*Numbers in this example may not perfectly add up because of rounding.

WATCH: How rent-to-own works

Is it a good deal for homebuyers?

The answer from James Laird, a Toronto mortgage broker at CanWise Financial and co-founder of Ratehub Inc., is a resounding no.

“I can’t really think of a single buyer for whom this offer would be attractive,” Laird told Global News.

Calculations by Global News suggest buyers may have to pay back more than they would save through the program. For example, let’s say our buyer who makes $100,000 a year repays the five per cent incentive after 25 years and that his home has been appreciating at an annual rate of three per cent — in line with the long-run average appreciation rate of real estate — over that period.

The house is now worth $881,591. If the buyer must return five per cent of that to the government, as in the numerical examples provided by Ottawa, the payback works out to around $44,000. That would be more than the $36,900 the buyer would save in monthly mortgage payments thanks to the incentive, assuming his mortgage rate remains constant.

“A prudent buyer would not take this deal,” Laird said.

Thomas Davidoff, of the University of British Columbia’s Sauder School of Business, had a different take. In a scenario where home prices have been climbing, the incentive would be simply skimmed off the final sale price, without homeowners having to repay out of pocket.

WATCH: Minister Duclos reveals new details about federal First-Time Home Buyer Incentive.

The ability to borrow and not pay interest may be worth a lot for the kind of cash-constrained homebuyer the federal program is likely targeting, Davidoff said.

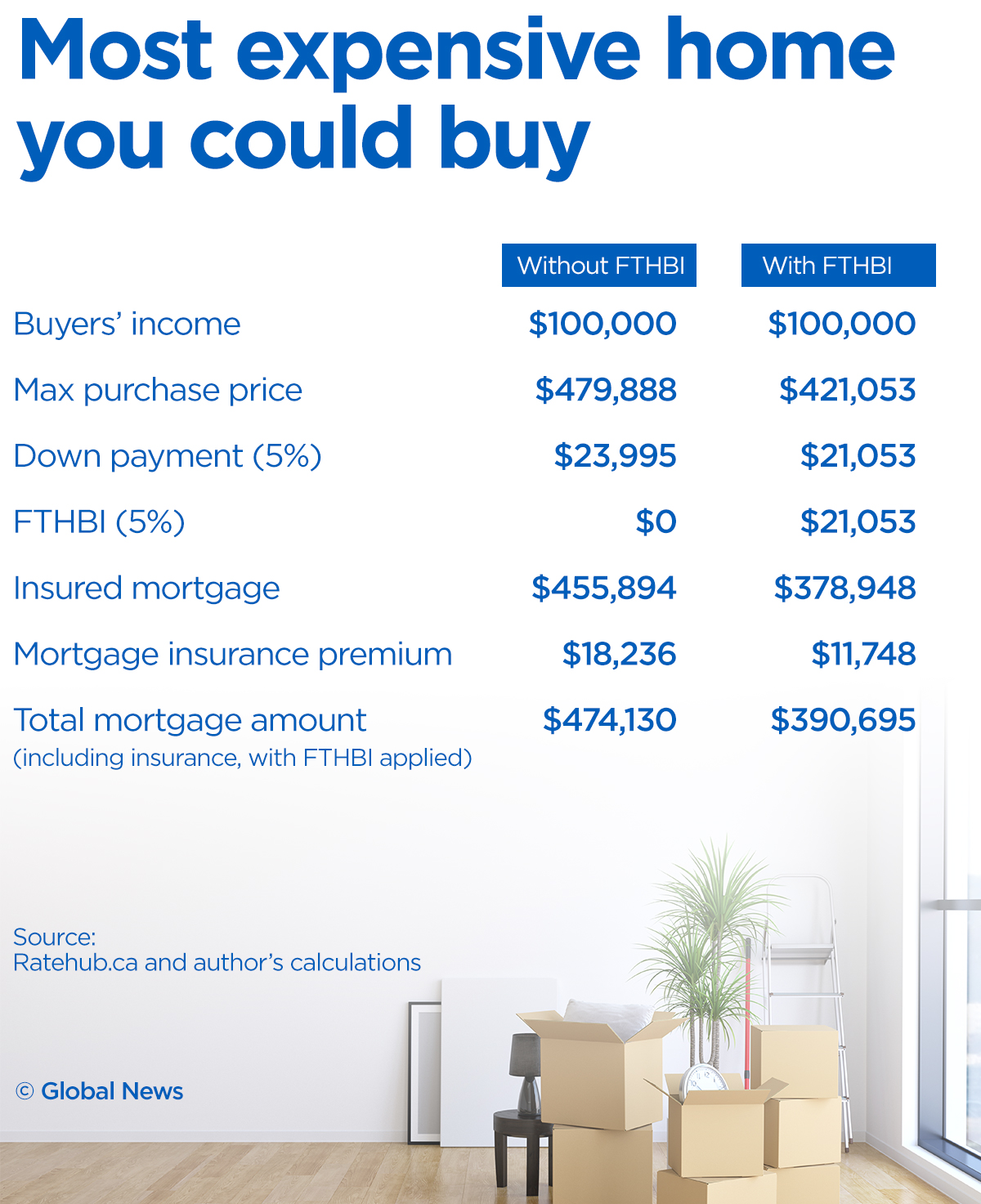

The other issue Laird sees is that the new program would force borrowers to settle for a cheaper home than they would otherwise be able to afford.

Let’s go back, once again, to our imaginary buyer with the $100,000 annual income. According to calculations provided by Ratehub, the biggest mortgage this buyer would qualify for with a five per cent down payment is just under $456,000. This would allow him to buy a home worth around $480,000.

The FTHBI, though, imposes a lower mortgage cap of around $379,000, which in turn lowers the maximum purchase price by almost $60,000.

Homebuyers who don’t want to borrow the maximum allowed under the current federal mortgage rules can simply buy a smaller home on their own, without a complicated loan from the government that they will eventually have to repay, Laird said.

Is it a good deal for taxpayers?

On Twitter, Davidoff called the program “too generous,” adding that the government should get a bigger cut of the gain from climbing home prices.

While the government would be exempt from costs like property taxes and maintenance, it also wouldn’t enjoy the benefit of using the property for shelter — one of the implicit dividends of homeownership, Davidoff said.

“There’s just a bit more of a giveaway than I would like to see,” he said.

Comments