Once relatively rare in Canada, blacklegged ticks are moving in across large parts of country, bringing with them the threat of Lyme disease.

They’re moving fast — between 35 and 55 km per year, according to Nick Ogden, director of the public health risk sciences division at the Public Health Agency of Canada’s National Microbiology Laboratory.

“The ticks started to expand in the U.S. in the 1960s, 1970s and continue to do so,” he said. They then got picked up by migratory birds and other animals and carried northward.

“So there’s been this sort of steady rain of ticks for quite some time and that’s increasing.”

At first, he said, the ticks didn’t stay. It was too cold. “By and large, Canada has been climatically unsuitable for the ticks but in recent decades Southern Canada has warmed, making it a much better place for ticks to set up home once they’re dropped in by migratory birds.”

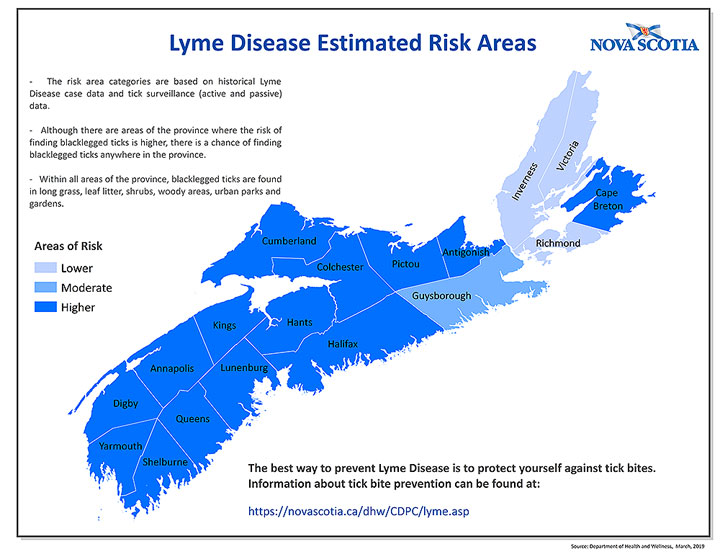

Now, people in parts of Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick and pretty much all of Nova Scotia face a risk of Lyme disease. Parts of B.C. do, too, though it’s due to a different species of tick that got there earlier.

And where the ticks are, Lyme disease follows. The number of reported cases rose from just 144 in 2009 to 2,025 in 2017, according to PHAC.

In Ontario, new Lyme disease risk areas include Thunder Bay and the Peel region, though all tick ranges have expanded, said Curtis Russell, senior program specialist with Public Health Ontario. Ticks have also cemented themselves firmly in the Ottawa area, where a high percentage carry the bacteria responsible for Lyme disease, he said.

WATCH: How ticks have spread across Ontario

In Quebec, Gatineau and the southwest part of the Outaouais, the northwest of the Estrie region, parts of Montérégie, the southwest of Mauricie and Centre-du-Québec are all known risk areas for Lyme disease, according to the province.

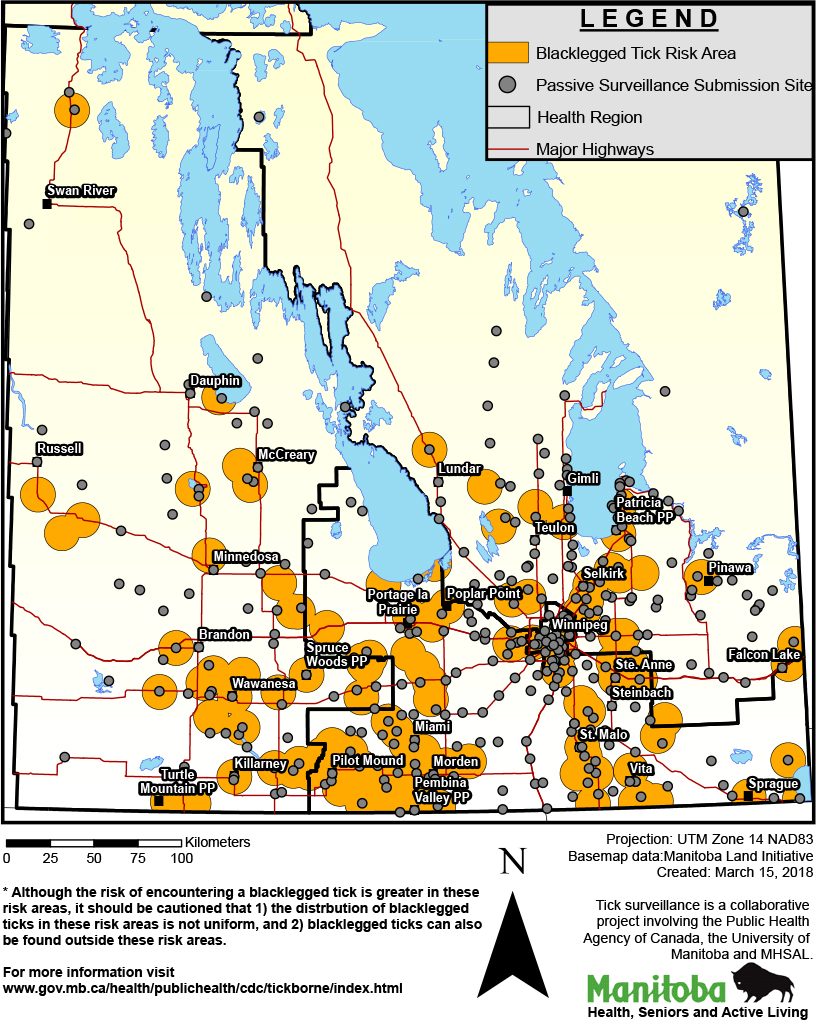

Get weekly health news

In Manitoba, risk areas include much of the southern part of the province, like Winnipeg, Brandon, Portage la Prairie, Selkirk and Sprague.

The southern half of New Brunswick, including the counties around Fredericton, Saint John and Moncton, are all marked as Lyme disease risk areas.

The entire province of Nova Scotia is also a risk area for Lyme disease.

Tick habitats

Just because you’re in a risk area doesn’t mean that the ticks are everywhere, Russell said. Ticks prefer wooded areas, and you’re unlikely to encounter them in the middle of a soccer field in Ottawa, for example.

“We usually find them in deciduous forests or mixed deciduous forests because there’s leaf litter they can go down into when it gets hot.”

Ticks dry out in the middle of a grassy field, Ogden said, which is also why they don’t like especially hot, dry weather. While Lyme disease cases in Canada have been trending upward, they dipped slightly during a particularly hot year, and again during a recent cold, rainy summer.

“If there is a particularly cold year, then again the ticks are not quite as active and often people don’t go out quite as much,” Ogden said.

Protecting yourself

The best way to prevent Lyme disease is to not get bitten by a tick in the first place. If you’re going into a wooded, brushy area, staying on the middle of the path will minimize the chances that you brush up against a waiting tick, Russell said.

You should also wear long pants and sleeves, preferably in a light colour so you can easily see any ticks that crawl on, he said. Wearing insect repellent containing DEET or icaridin will also help to ward off ticks and mosquitoes.

Not every tick bite leads to Lyme disease, but it’s important to get ticks off of you quickly, said Dr. Kieran Moore, chief medical health officer for Kingston, Ont., which has had Lyme disease cases since about 2006.

“They want to have at least 72 hours to have a good long blood meal from us and they have an anesthetic so you don’t feel that they’re there and they’re just getting bigger and bigger, like a juicy raisin on you, and then fall off.”

The longer they’re on, the higher the chance of the tick transmitting Lyme disease, Moore said. So, doing a daily tick check is important if you’re spending time outside. You should examine your whole body carefully, since ticks may be as small as a poppy seed.

WATCH: How to prepare for and handle ticks in the summer

One of the most common signs of early Lyme disease is an “expanding red rash,” he said. It’s often compared to a bullseye. Other symptoms include a persistent fever, muscle aches, chills and headaches.

“If you don’t see the rash it still does not mean you don’t have Lyme,” he said. “You still should see a physician especially if that’s occurring during the peak season of June, July and August.”

Public health officials like him are trying to educate the public as well as front-line health workers on how to recognize Lyme disease, since it’s relatively new in Canada, he said.

“Lyme is a difficult diagnosis because if you don’t catch it early it can affect brain and joints and neurological tissue and sometimes it can look like a number of common illnesses that we would see daily in our offices,” he said.

If doctors don’t have Lyme on the mind, especially during the summer he said, they could “potentially miss the diagnosis.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.