It’s been 25 years since Nelson Mandela won the first all-races election in South Africa, triumphing over the legalized racial segregation of apartheid and establishing himself as a hero only a scant few years after he was widely labelled a terrorist.

Mandela was once considered a criminal in his own country and a communist in the eyes of the United States, where he remained on a terrorism watch list until 2008.

Mandela’s terrorist label has largely faded into the background as South Africa marks the anniversary of his historic election victory on April 24, 1994. However, it was the dominant narrative around him when he began his 27 years behind bars in 1962.

“I’m an ordinary human being with weaknesses, some of them fundamental,” Mandela told an audience at Rice University in Houston in 1999.

“I am not a saint, unless you think of a saint as a sinner who keeps on trying.”

Here’s why Mandela the “sinner” was once considered a terrorist.

A hard-edged political activist

Mandela became involved in politics from a young age, and was one of the first to call for armed resistance to apartheid through his political party, the African National Congress (ANC).

He was kicked out of university for organizing a student strike in 1940, founded the ANC’s Youth League in 1944 and started aggressively campaigning against apartheid in the years that followed. He encouraged black South Africans to defy the government’s racist segregation laws around education, employment, housing and marriage, and was banned from several locations for his efforts.

Mandela and the ANC continued to encourage anti-apartheid protests in South Africa until 1960, when the government banned the party following several violent incidents. The worst of these clashes became known as the Sharpeville Massacre, during which police opened fire on a crowd of anti-apartheid marchers, killing 69 people and wounding 186 others.

Mandela responded to the ban by going underground in 1961 to found the ANC’s armed wing, the Umkhonto we Sizwe, which means “Spear of the Nation” in Zulu. He spent the next year travelling throughout Africa and Europe, studying guerrilla warfare and building support for the ANC abroad.

Mandela would later say in an interview that the ANC’s armed struggle “was forced on us by the government.”

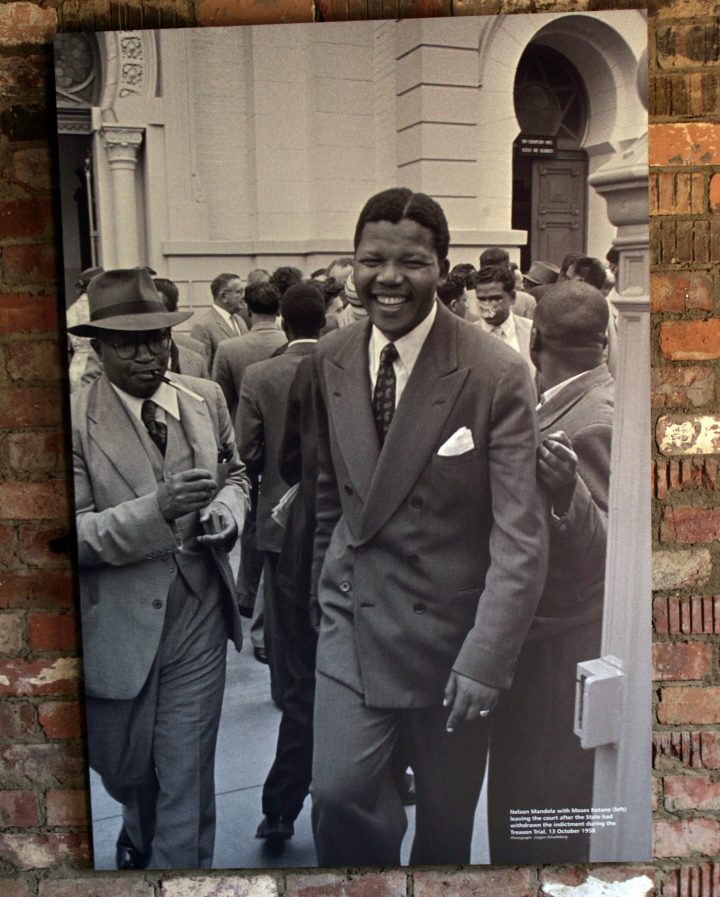

South Africa’s government charged Mandela with incitement and illegally leaving the country upon his return in 1962, and sentenced him to five years in prison. The courts extended Mandela’s sentence to life in 1964, after he and several other ANC leaders were convicted of treason for trying to sabotage the government.

His critics painted him as a dangerous terrorist bent on leading a destructive communist revolution at the time, and they warned that his ideas would touch off tremendous bloodshed.

“I do not deny that I planned sabotage,” Mandela told the court at his trial. “I did not plan it in a spirit of recklessness, nor because I have any love of violence. I planned it as a result of a calm and sober assessment of the political situation that had arisen after years of tyranny, exploitation and oppression of my people by whites.”

A political prisoner

Get daily National news

Mandela and his ANC compatriots were shipped off to the notorious Robben Island penal colony after their trial in 1964. The government prohibited news media from publishing Mandela’s photos or quotes, but he and his allies were still able to smuggle messages out of prison throughout their term. Meanwhile, the exiled ANC urged black South Africans to make the country “ungovernable” until apartheid was ended.

Many people were killed in protests, and the ANC’s armed wing was linked to several high-profile bombings that killed South African civilians throughout the 1980s, prompting some among the country’s white minority to blame the “terrorist” Mandela.

Mandela ultimately served 18 years on Robben Island and 27 years behind bars overall. He eventually became the world’s most famous political prisoner, as foreign governments moved to sanction and condemn South Africa for apartheid.

WATCH BELOW: Nelson Mandela’s Robben Island legacy

“People tend to measure themselves by external accomplishments, but jail allows a person to focus on internal ones, such as honesty, sincerity, simplicity, humility, generosity and an absence of variety,” Mandela once said, according to a quote at the Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg. “You learn to look into yourself.”

Party banned in the U.S. and Canada

Mandela’s plight earned him plenty of international attention and sympathy through the 1980s.

However, U.S. President Ronald Reagan and U.K. Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher dragged their heels on the apartheid issue through much of that period, amid Cold-War concerns that the ANC was accepting help from the Soviet Union. Thatcher described the ANC as a “typical terrorist organization,” while Reagan condemned terrorist and communist “elements” within the party.

The U.S. Department of Defense added the ANC and its leader, Mandela, to a list of “key regional terrorist groups” in 1988. The report cited several bombing incidents perpetrated by the group between 1980 and 1988.

“Although ANC operations have not posed any direct threat to U.S. assets or personnel in South Africa, the indiscriminate nature of recent attacks raises the danger of Americans becoming inadvertent victims,” the report said.

Canada also had a complicated relationship with the anti-apartheid movement. Then-prime minister Brian Mulroney urged Thatcher and Reagan to do more to help Mandela and his anti-apartheid crusade.

However, the Canadian government also banned members of the ANC from entering the country without a visa. The ban stood for decades, and was not lifted until 2012.

Terrorist no more

The South African government started moving toward an end to apartheid in 1989, after newly-elected president F.W. de Klerk came to power.

De Klerk set Mandela free on Feb. 11, 1990, and allowed him to resume control of the newly-restored ANC party in South Africa ahead of elections in 1994.

WATCH BELOW: Nelson Mandela celebrates his first day of freedom

In his autobiography Long Walk to Freedom, Mandela fondly recalls the moment he left the prison hand-in-hand with his wife, Winnie.

“As I finally walked through those gates … I felt — even at the age of seventy-one — that my life was beginning anew,” Mandela wrote.

Mandela and de Klerk shared the Nobel Peace Prize in 1993, a year before Mandela won the presidency in a landslide all-races vote.

“Never, never and never again shall it be that this beautiful land will again experience the oppression of one by another and suffer the indignity of being the skunk of the world,” he said in his 1994 inauguration speech.

“Let freedom reign. The sun shall never set on so glorious a human achievement! God bless Africa!”

WATCH BELOW: Remembering Nelson Mandela after his death in 2013

Mandela remained on the U.S. terror watch list for nearly two decades after his release, although he was still allowed into the country to visit the United Nations and the White House. Congress passed a measure to remove Mandela and the ANC from the U.S. terror watchlist in 2008, at the urging of Secretary of State Condoleeza Rice.

Mandela also paid three visits to Canada after his release, and was granted honorary citizenship in 2001. However, the honour was delayed because Saskatchewan MP Rob Anders of the Canadian Alliance, refused to vote for a former “communist and terrorist.”

Anders stood by his comment after Mandela died in 2013, and highlighted an anti-Mandela obituary that called him a terrorist.

“I have previously provided my thoughts on Nelson Mandela,” he told Global News in an email at the time. “I will let history be the judge.”

— With files from Reuters and the Associated Press

Comments