The demand for French immersion schooling is growing across Canada, as parents hope to give their child a leg up with a second language.

With more and more parents choosing to put their kids in bilingual schools, this is met with a problem — a lack of French teachers in most jurisdictions means families are fighting for limited spots.

In January, dozens of parents in Vernon, B.C., spent a chilly night outside lining up outside a French immersion school in order to ensure their child got a spot. Many prepared to camp out with chairs, sleeping bags, tents, and campfires, hoping to get on the French immersion list.

“The demand for French immersion is on the rise because increasingly parents are aware that learning a second language is good for the brain,” Graham Fraser, Canada’s former commissioner of official languages, said.

But Fraser said, one of the problems is getting quality staff who can master the language.

WATCH: B.C. parents line-up overnight in January for French immersion registration

Teacher shortage

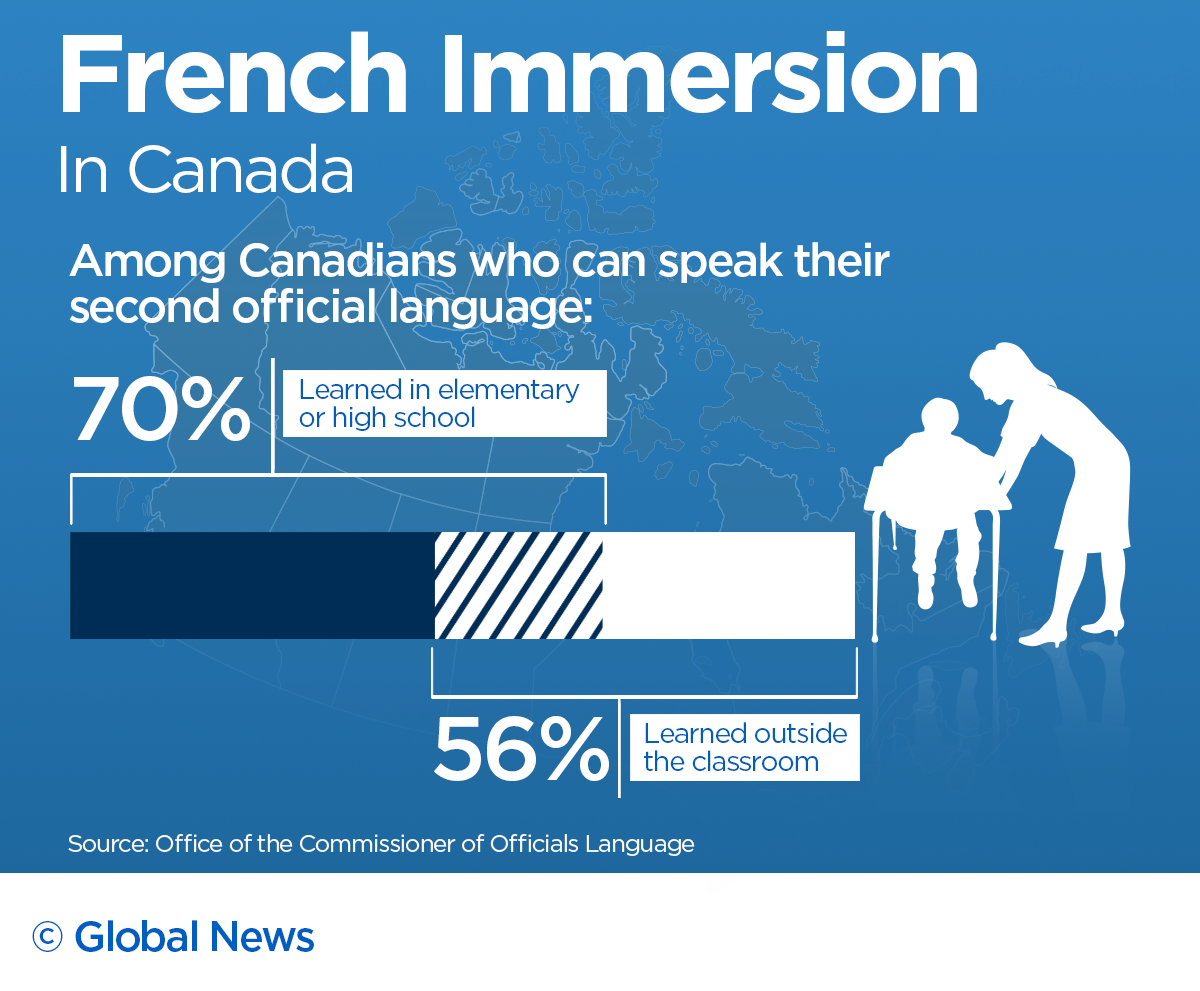

A study released Wednesday by the Office of the Commissioner of Officials Languages says there are challenges in the country when teaching French-as-a-second-language (FSL), due to low teaching supply and high parent demand.

In 2015-2016, around 430,000 students were enrolled in French immersion programs in Canada, compared to 360,000 in 2011-2012 — an increase of nearly 20 per cent in just four years (at a time when the total student body has remained the same), the study said.

The study also said a majority of Canadians believe more needs to be done so young people can become bilingual.

Some Canadian school districts use lottery systems to accept students, while others cap the number of students they’ll take or provide limited-time online registration, as is the case in Ontario.

But the demand is not being met with supply.

“A shortage of teachers means that many aren’t going to be as good,” Andrew Campbell, a teacher in Brantford, Ont., said.

He said there are many school boards in Ontario struggling to find quality fluent teachers, leaving school boards with the option of hiring educators with sub-par French skills or not filling the vacancy at all.

Last year, the British Columbia government was so desperate for French teachers that it sent a delegation to try to recruit French teachers from France and Belgium.

In 2017, the Halton Catholic District School Board in Ontario announced that it was considering cancelling its French immersion program over a staffing crisis due to the difficulty of recruiting and retaining FSL teachers.

Get breaking National news

Why the demand is growing

Employment opportunities

“Learning a second language stimulates the brain, it’s good for the intellectual development of a child and is overwhelmingly a positive element,” Fraser said, adding that it creates job opportunities.

There are positions across Canada that demand applicants can speak both French and English. For example, the federal government of Canada is the largest employer in the country and the largest employer of bilingual workers.

WATCH: Retired NB teachers says all English students should learn French as a second language

A 2006 poll by Decima revealed nearly 70 per cent of Canadians felt bilingualism improved employment opportunities.

According to a study by the Association for Canadian Studies, Canadians who speak both languages earn about 10 per cent more than those who only speak English.

‘Elitism’

Campbell said French immersion schools sometimes are seen as welcoming upper-middle-class families and not students with special needs or immigrants — leading to an elitist view.

“There is a perception with parents that it is better for their kids,” he said.

“Stats show that the makeup for French immersional classes is mainly children with high incomes and there are fewer numbers of special education students. So because of that, parents think it is a better learning environment for their children, and not necessarily that they want to learn a language,” he said.

WATCH: Growing demand for French immersion programs in Edmonton

According to a 2010 a Toronto District School Board study, French immersion students tend to come from “less challenging family circumstances.”

In 2009-2010, a majority of the French immersion students were from the highest family income decile (23 per cent) and only four per cent of the French immersion students were from the lowest family income decile, the study said.

The study also highlighted that immigrant families are less likely to enroll in French immersion schools.

Is French immersion creating bilingualism?

French immersion schools were first introduced in Quebec in the late 1960s.

“It was for Anglophone parents who wanted to prepare their children for French culture,” Campbell said. “Their kids lived in a francophone environment … and parents wanted their kids to be able to go to the mall and order food in French.”

WATCH: 50 years of French immersion

French immersion schools then spread throughout Canada, and into areas that areas where many children don’t have the ability to speak French outside the classroom, which creates an “artificial situation,” Campbell added.

“It is much easier for immersion students in Quebec, as when they step out of the classroom they are in French-speaking environments,” Fraser said. “But if you are in Winnipeg or Brampton, the environment may be Anglo speaking. ”

From 2011 to 2016, there was an overall increase in the national bilingualism rate, from 17.5 per cent to 17.9 per cent in 2016, according to Statistics Canada.

But the rate remained much higher among Canadians whose mother tongue is French (46.2 per cent), and much lower among Canadians whose mother tongue is English (9.2 per cent) or another language (11.7 per cent).

The study from the Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages said the bilingualism rate among non-Francophones is not expected to increase for the foreseeable future.

“It is an interesting dynamic,” Campbell said. “If the argument is the French immersion program is designed to create bilingual citizens … there doesn’t seem to be a whole lot of evidence that it works well. I don’t know how effective it is as teaching kids to speak French.”

However, according to Statistics Canada, the reason bilingualism rates in Canada may have stagnated is due to Canada’s increased immigration rates.

“A strong majority of these immigrants had neither English nor French as their mother tongue, and less than six per cent of these recent immigrants had knowledge of the two official languages when they arrived in the country. This directly impacts the evolution of Canada’s English and French bilingualism rates,” Statistics Canada said.

Fraser said that even if French immersion does not create bilingualism, it does provide a building block for language mastering, which helps to further learn the language of adults.

WATCH: N.B. still not getting bilingualism right, languages commissioner says

Solutions?

The federal government has set a goal of increasing Canada’s bilingualism rate from 17.9 per cent to 20 per cent by 2036, which it plans to achieve by raising the bilingualism rate of English speakers.

But the challenges of French immersion, such as inadequate resources and too few teachers who speak the language, need to be addressed if this goal is to be accomplished, the Office of the Commissioner of Officials Languages said.

“More than ever, Canadians want their children to have access to the advantages that come with being bilingual, yet at the same time, there is a chronic and critical shortage of FSL teachers,” Commissioner of Official Languages Raymond Théberge said in a statement. “No matter where they live, every child in Canada should have the opportunity to become bilingual.”

WATCH: Not enough teachers for French immersion

In the study that was released Wednesday, the office recommended standardizing FSL teacher qualifications across Canada, creating more second-language development opportunities for teachers and exploring ways to facilitate the job process for French-speaking immigrants coming to Canada with an education degree.

“Without addressing the challenges in FSL teacher supply and demand, it is unlikely that access to FSL education will improve and, consequently, unlikely that the overall English/French bilingualism rates among non-Francophones will increase in the foreseeable future,” the study stated.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.