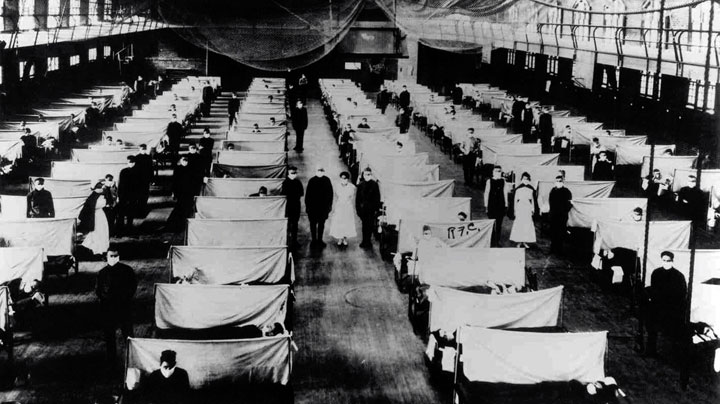

The First World War was one of the deadliest conflicts in human history. But not as deadly as the flu.

The Spanish flu, which reached its peak in the fall of 1918, killed somewhere between 20 million and 40 million people, with some estimates reaching as high as 50 million. In Canada, it killed around 55,000, mostly young adults.

The virus spread rapidly around the globe, carried in many cases by millions of soldiers travelling to and from Europe.

And now, 100 years later, scientists are once again looking back to the pandemic and what it can tell us about how to prepare for the next one.

Because the question isn’t if it will happen again, they say, but when.

A unique virus

The Spanish flu was unique in a number of ways. Unusually, it killed young, healthy individuals rather than the elderly or children like most flus, said Dr. Gerald Evans, chair of the division of infectious diseases and a professor of medicine at Queen’s University.

In the late 1990s, researchers were able to re-create it, using material from a frozen victim’s corpse found buried in the Alaskan permafrost.

They were able to learn a few things about the virus itself. First, the re-created virus was unusually deadly, killing test mice in just a few days. It also affected more than just lung cells, which is unusual.

The Spanish flu was also brand new at the time, Evans said. It was a “recombined” virus, meaning, “There were pieces of it from a bunch of different viruses, influenza viruses, that came together to create the unique H1N1 strain that it was.”

Get weekly health news

The result: people didn’t have much immunity to it, with deadly consequences.

New flus

The 1918 flu virus was unique, but new flu viruses are created all the time, Evans said.

“It’s really just a throw of the genetic dice that we don’t have a Spanish flu that’s yet popped out.”

Lots of animals, like chickens and other birds, carry flu viruses, though they’re not always easily spread to humans.

That’s where animals like pigs come in, he said. Pigs can catch pig flu, human flu, and they can catch avian flu, and they can mix them both together to create a brand-new virus capable of infecting humans.

WATCH: What to expect this flu season and how the flu shot can help

The 2009 flu pandemic was a re-assortment of a number of different kinds of swine, avian and human flu strains, he said. “It was a new virus which nobody had seen in the human population before.”

“We were just fortunate that it didn’t kill people.”

Dealing with the flu

In many ways, the world is better-prepared to deal with a flu pandemic than it was in 1918.

“Almost everywhere in the world, and Canada is a good example of it, we now have pandemic flu plans in place, which allow us to in an organized and systematic fashion address it when and if it emerges,” Evans said.

A paper published in early October in the journal Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology found that global influenza surveillance programs are constantly monitoring for flu outbreaks, and authorities are acting on that information — by slaughtering infected poultry, for example — to prevent them from spreading.

And our medical capability and understanding has grown, the paper found, so that the flu is easier to recognize and people can receive better care while sick.

Many countries, including Canada, also stockpile antiviral drugs that can be used on flu patients, Evans said, hopefully buying time in a pandemic until a vaccine can be developed to protect the broader population.

New challenges

But there are new risks, too. “We now face new challenges including an aging population, people living with underlying diseases including obesity and diabetes, climate change and a future where current antibiotics will be ineffective for treatment of secondary bacterial infections,” wrote study co-author Dr. Carolien van de Sandt of the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity at the University of Melbourne.

“In 1918, a large proportion of the elderly population was, to some extent, protected from a severe infection as a result of pre-existing immunity that they acquired during an infection with a previous influenza virus that resembled the 1918 virus,” said another co-author, Katherine Kedzierska, also of the Doherty Institute. She’s not sure that will be the case during future pandemics, meaning that more elderly people will be severely infected.

“What we know from the 2009 pandemic is that obese and diabetic people were significantly more likely to be hospitalised with, and die from, influenza,” said co-author Dr. Kirsty Short of the University of Queensland. “We also know that people with obesity have an impaired immune response to the seasonal flu vaccine, which leaves this population group further at risk of severe disease.”

Air travel also means a virus can spread from one continent to another in just hours.

Pandemic life

Evans hopes that in a severe pandemic, everything goes according to plan. But he acknowledges that there’s a lot of potential for something to go wrong. This could mean a lot of disruption in people’s day-to-day lives.

If 25 per cent of people exposed to the flu virus caught it, which Evans says is a usual supposition for pandemic planning, it would have a big impact.

Imagine if one in four people you encounter in your day was home sick, he said. “All of a sudden you’re not going to have deliveries of food, of gasoline, of lots of the stuff that we kind of take for granted in our day-to-day lives.”

Maybe schools are closed so that kids don’t transmit the virus, meaning even healthy parents have to stay home to take care of them, he said.

Despite that, he’s cautiously optimistic.

“Pandemic plans are in place. All countries have them. Here in Canada all the countries and the provinces have them. We’ve stockpiled stuff. We’re pretty sure we’re ready in case it hits.”

Canada just needs to “Keep our fingers crossed that it doesn’t kill a lot of people, that we can distribute our antivirals around and that we can get a vaccine developed so that we can minimize that impact,” Evans said.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.