Muhammed Ali sat on the couch in the prison commander’s office, still wearing the T-shirt and sweatpants he had on four months ago when he was captured by Kurdish fighters in northeast Syria.

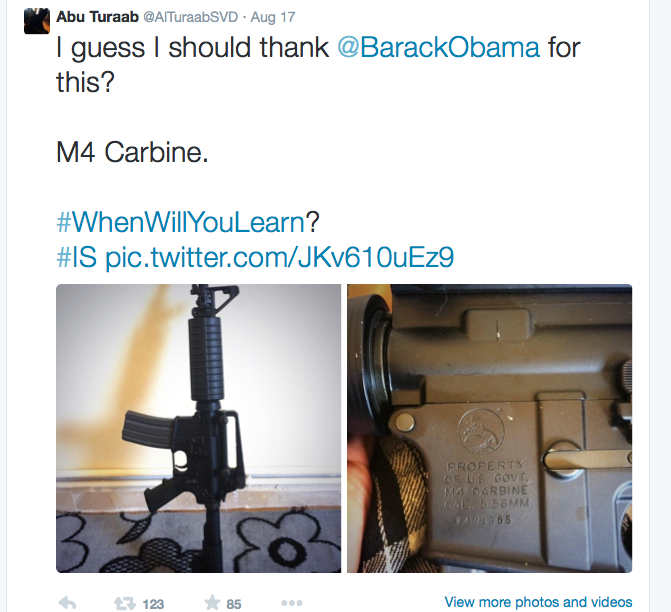

Four years ago, the Canadian was a defiant voice of the so-called Islamic State, using his social media accounts to spread beheading photos, threats and incitement messages to an English-speaking audience.

But now he looked defeated.

“I’m just tired of everything,” he told Global News, which interviewed him last weekend at a facility run by the Syrian Democratic Forces, the U.S.-backed fighters who control the country’s northeast.

WATCH: Canadian ISIS fighter speaks about time as a sniper

Balding and beardless, with dark rings around his eyes and a quiet voice that seemed at odds with his belligerent online persona as Abu Turaab Al-Kanadi, he said he wanted to come back to Canada.

He said he didn’t care if he was arrested on arrival and insisted he wasn’t a threat.

“If I wanted to blow things up, I would have blown things up four years ago,” he said. “I wouldn’t have had to come here.”

The Mississauga resident, who left Toronto to join ISIS in April 2014, said he was attempting to cross into Turkey and return to Canada when Syrian fighters from Kurdish People’s Defense Units, or YPG, caught him near the border in a town called Ras al-Ayn.

WATCH: Ralph Goodale mum on what Ottawa will do with returning Canadian ISIS fighters

They brought him to a building in a compound guarded by gunmen. The faded sign above the metal gate said it was once the Syrian Department of Immigration and Passports, before civil war turned the country into a graveyard.

Ali’s wife, Rida Jabbar, who is from Vancouver, and their two children, who were both born under ISIS rule and have never seen Canada, were also taken into custody and are being held at a detention camp not far away.

The question is what to do with them.

Kurdish authorities want Ottawa to take back Ali and at least a dozen other Canadian ISIS fighters, women and children they are holding. But Ali said Canadian officials had not visited him, or even spoken with him on the phone.

“You guys are the first Canadians I met,” he said.

In a two-hour interview conducted by Global News and terrorism researcher Amarnath Amarasingam, Ali spoke openly about his role in ISIS and why he ultimately abandoned the group.

Ali consented to be interviewed on camera. His captors were not present in the room during the meeting. The SDF asked Global News to sign a form requiring “adherence to international human rights laws” and “not to force the detainee to answer.” Questions about the location of the detention facility were also off-limits.

“I really did get sick of them,” Ali said of ISIS. “I mean, there was loads of problems, but the most basic thing was they betrayed the Syrian people and the foreigners that came here.”

A Toronto-based academic who studies foreign fighters, Amarasingam said Ali seemed disillusioned and appeared to have undergone a change of heart as a new father trying to raise young children under the coalition anti-ISIS campaign.

READ MORE: Canada’s plan for managing the return of ISIS fighters revealed in documents

While Ali’s responses were consistent with those of other disenchanted fighters, Amarasingam said the remorse could also be feigned, and it was unclear whether he had abandoned his commitment to jihadist violence or had merely soured on ISIS as an organization.

“Just based on a two-hour interview, it’s kind of difficult to know whether he’s lying, whether he’s kind of playing the regret card just to get back to Canada,” said Amarasingam, a senior research fellow at the Institute for Strategic Dialogue in London.

Ali had no complaints about Canada, which he said became his home at the age of seven or eight when his parents immigrated from Pakistan. He grew up in Mississauga playing basketball and attending a Catholic high school before starting at Ryerson University in 2008.

Maybe because he “wasn’t mature enough,” he felt lost, depressed and “stopped going to classes, stopped showing up for tests,” he said. A Toronto-based Muslim convert named André Poulin whom he befriended had a strong influence on his fate but didn’t recruit him, he said.

After Poulin died fighting in Syria in 2013, Ali worked in northern Alberta to raise money for a plane ticket to Turkey. When he confided that he wanted to fight abroad, his father took him to an imam to talk him out of it, but Ali wasn’t swayed. “To me it seemed like the right thing to do at that time,” he said.

“At that time the regime was basically going all out on the civilians, so I decided to come here and help the rebels in their fight against the regime and against Assad,” he said. “At that time it was very simple because a lot of the foreigners were coming in for that reason. A lot of them were English-speaking.

“So I decided, why not?”

He left Toronto’s Pearson airport for Istanbul in April 2014 and, with the help of a Swedish extremist he met online, crossed into Syria northeast of Azaz. ISIS asked him questions and sent him to basic training, which lasted 21 days.

When Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi declared himself the head of the Islamic State in June 2014, Ali said he was supportive, believing it would unify the competing anti-Assad armed factions, although it didn’t.

At first, he said, he was sent to work for the ISIS oil and gas ministry, but there was little for him to do, so he spent much of his time online and quickly became a prominent social media propagandist, even as his various accounts were suspended.

READ MORE: Canadian member of Islamic State caught, but RCMP struggle to lay charges against ISIS fighters

His online posts were taunting, at times gruesome. He posted photos of ISIS executions and talked about playing soccer with severed heads. As ISIS was throwing homosexuals off rooftops, he said they should be killed. Following the October 2014 terror attacks in Quebec and Ontario, he gloated and called for more.

“I’ve learned a lot of things,” he said when reminded of those posts. “2014 was a long time ago, different time. Killing of civilians is not really justified Islamically. I haven’t seen any justification yet. It doesn’t really help anyone because … it’s not really a good idea.”

He met his wife at a house where women waited to be married off to ISIS fighters. She was an Afghan-Canadian who had come to Syria four months after him. Their courtship was pragmatic. “We had a meeting for about 30-40 minutes,” he said. And that was it. “I married her.”

While he said he hung out mostly with Australians, he occasionally encountered other Canadians, like Farah Shirdon of Calgary, whom he said died in an airstrike in Raqqah in 2017. Another Canadian led a battalion of English-speaking fighters, he said, and a third, who went by Abu Rudwan, narrated the ISIS execution video Flames of War.

But he downplayed the numbers of Canadians in ISIS, saying estimates of 80 to 100 were too high.

“I mean there’s like five Canadian guys. Two killed in Raqqah, me,” he said. “I heard there’s another one in a different prison. And maybe one or two still in ISIS. Not a lot of Canadians here.”

From the oil ministry, he joined a sniper and reconnaissance unit at a camp in Al-Tabqah. “And pretty much been doing that for the last four years,” he said. He did “mostly recon, some sniping and some training,” he said.

“Most of the time I was doing recon, even in the sniping units, I was a spotter.” Asked if he had killed, he said ISIS did not try to confirm whether they had hit their targets.

During the siege of the ISIS capital Raqqah that began in 2016, he said he moved to Al Mayadin, where the terror group’s leadership was relocated. But by late that year, he was losing faith in ISIS, he said.

He felt ISIS had shifted its focus from toppling the Assad regime to fighting other armed factions. And he was upset about the treatment of foreign fighters he said were either used as cannon fodder or tortured and killed on the premise that they were spies.

“They portray themselves in the media as they’re an Islamic state,” he said. “But there are many things here that are not in Islam. Like it is a lot of lies, things like that.”

READ MORE: Coalition forces in Syria, Iraq targeted three Canadians, secret document says

He also began to struggle with ISIS terrorist attacks, he said. He denied he was involved in the ISIS branch that trained foreigners to enter Western countries and carry out attacks.

“No, no,” he said. “But there were people trained and they were sent back to Europe. And you’ve probably seen what happened in France and things like that. But I never met anyone who was trained in that.”

Ready to give up ISIS, he said, he spoke to his wife’s father in Dubai, who contacted the Canadian government. “They said if you want to come home the best thing is to go to Turkey, because from there they can help us get back.”

The family left Ash Sha’fah, near the Iraqi border, with Ali hidden in a secret compartment in a transport truck. They changed to a car and then to a different car, but as a Pakistani-Canadian, he would have stood out and the Kurdish forces pulled him aside.

“They took me to a house, they beat me up a little bit. Once they found out I was Canadian and my wife was Canadian they took me to prison and took her to camp. Then they transferred me from that prison to this one and I’ve been here since.”

For the first three months, he was in solitary, where the lights were always on, he said. He is now in the general population and shares a cell with four Europeans, five Iraqis and four Syrians.

The Kurds, Americans and British have interrogated him, he said. They asked him “everything — about myself, about ISIS, about other people, things like that.” He said he had not been mistreated or tortured.

WATCH: What happens when an ISIS member returns to Canada? The story of one Toronto-area man

The Canadian government may not be in a hurry to repatriate ISIS members like Ali following the uproar in the House of Commons last year over a Toronto-area man who said he had served in ISIS but had not been arrested.

With a federal election next year, the government of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau may fear the optics of repatriating ISIS members when it remains uncertain the RCMP would be able to gather enough evidence to arrest them.

READ MORE: ISIS leader al-Baghdadi appears to call for attacks on Canada in new audio recording

Ali sounded resigned to being arrested upon arrival in Canada. “I mean, obviously, they’ve got things that they want to charge me for,” he said. “It is what it is. I have to go back home. I can’t spend any more time here, man. Four years is enough.”

Was it all a mistake?

“Well, if you say it’s a big mistake, then you’re going to spend the rest of your life banging your head on the wall. I mean, I don’t know man, the only thing I care about now is my wife and my kids,” he said. “I don’t even care about anything else. I don’t care about this country or these people here.”

In one of his many social media posts after joining ISIS, Ali said he wasn’t Canadian anymore. He said his passport expired in 2014 and was taken from him. But throughout the interview, he repeated that all he wanted was to go home.

“I’ve learned my lesson,” he said. “Four years, I mean, it’s pretty much taken everything out of me. Don’t know, man. I’m not going home to do anything stupid or anything like that. I was never in trouble growing up, never got in trouble and I’m not looking to get in trouble once I go back.”

“I just want to go back and live my life, that’s it.”

Comments