Terri-Lynne McClintic is less than a decade into her sentence for the killing of eight-year-old Tori Stafford in 2009.

She was handed a life sentence with no chance of parole for 25 years after she pleaded guilty to first-degree murder the following year.

But on Wednesday, it was revealed she won’t spend her entire sentence in a prison.

Coverage of healing lodges on Globalnews.ca:

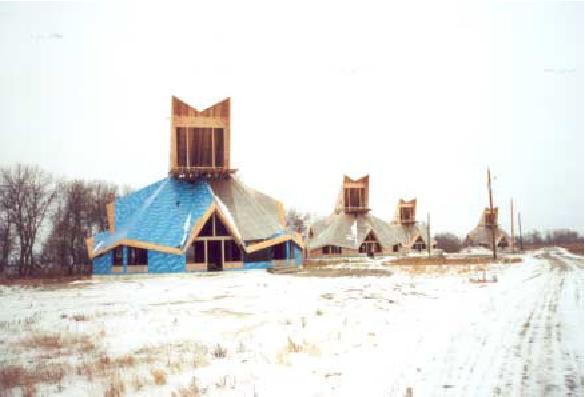

Instead, she’s been transferred to the Okimaw Ohci Healing Lodge, a facility on the Nekaneet First Nation close to Maple Creek, Sask.

The transfer has generated widespread outrage, from the House of Commons to the family who lost their little girl nine years ago.

McClintic’s transfer will be reviewed, but this isn’t the first time a convict’s move to Okimaw Ohci has triggered such a reaction.

READ MORE: Corrections official stands by decision to transfer McClintic to healing lodge

Last year, the family of four people who were killed by a drunk driver was shocked to learn that Catherine McKay, the woman who was sentenced to 10 years in connection with the incident, had been moved there.

Both McClintic and McKay have entered a facility that serves as an alternative to federal institutions, where Indigenous people develop a closer relationship with their culture using traditional practices and a healing plan with a “holistic approach” — although non-Indigenous people can enter them, too.

But how well do healing lodges work? How do residents benefit from living in them, and how much do they keep them from re-offending?

Why a healing lodge?

Healing lodges have operated in Canada since 1995, and they were developed in response to Indigenous incarceration rates that showed them over-represented among correctional populations.

“It was to bring cultural programming or traditions to Indigenous people in prison,” said Vicki Chartrand, a Bishop’s University sociology professor who has focused on Indigenous incarceration.

When settlers colonized Indigenous lands, the people were dispossessed of many aspects of their way of life, she explained.

“In many ways, the prison took over when assimilation policies failed or receded,” she said.

Indigenous sisterhoods and brotherhoods formed inside institutions and fought to bring their spirituality into the system.

“Before it was only the chaplains that were providing any sort of service,” Chartrand said.

They’re often located in “beautiful physical settings” that are “conducive to relaxation,” and they “may allow offenders to open up emotionally and begin dealing with the factors that have contributed to their criminal behaviour.”

Get weekly health news

These facilities focus on “healing and harm reduction through the provision of cultural teachings, and engaging in spiritual practices,” the paper said.

READ MORE: What are Correctional Service Canada healing lodges?

There are separate facilities for women and men; the ones that take in women are minimum and medium security, while men’s facilities are minimum security.

McClintic was previously incarcerated at Ontario’s Grand Valley Institution, a multi-level facility for women. She was designated as a medium-security inmate, and Okimaw Ohci takes in both minimum- and medium-security offenders.

Lodge residents have healing plans, similar to correctional plans, that specify areas they have to work on using a “holistic approach,” said a 2002 study by the Correctional Service of Canada (CSC).

Such plans can see them focus on issues such as substance abuse, employment, education and family.

The holistic approach can also include traditions such as sweat lodges, healing circles and pipe ceremonies.

For many of them, said Chartrand, the healing lodges can represent the first time that they encounter anything from their culture.

“While the healing lodge is still a prison, it offers Indigenous people some parts of their way of life that has been stolen from them since colonization,” she said.

Healing lodge residents live in shared spaces, they cook and clean together, and they can engage in programming such as parenting courses and employment training.

The people transferred to healing lodges have been known to have a higher risk of re-offending than Indigenous offenders in minimum security institutions.

Residents’ criminal histories were seen to be “fairly similar” to Indigenous inmates in minimum security, in a 2002 study by the Correctional Service of Canada (CSC).

However, they were seen to pose a high risk to re-offend (53 per cent) compared to minimum security inmates (45 per cent).

Their reintegration potential was also observed to be lower (45 per cent versus 33 per cent).

“This is important, because it indicates that it is not the ‘easiest’ cases that are being transferred to healing lodges,” the study said.

Repeat offending

There are numerous metrics for determining the success of a healing lodge — recidivism, or the potential of a resident to offend again, is one that has been cited in previous research.

Indigenous offenders generally seem to have higher rates of repeat offending than non-Indigenous offenders, said the 2002 study.

Indigenous involvement with elders and immersion in cultural and spiritual practice have been correlated with a drop in recidivism.

“Since healing lodges include elders and focus on cultural and spiritual activities, the use of healing lodges may contribute to a reduction in recidivism; this may ultimately result in a decrease in aboriginal incarceration rates,” the study said.

There are conflicting findings around repeat offences for residents of healing lodges, as compared to minimum security.

The 2002 study found that, of 426 residents who had been released from healing lodges between 1995 and 2001, 19 per cent of them (83) had been readmitted to corrections within four years.

That compared to 13 per cent for offenders in minimum security facilities — “significantly higher,” the study said.

READ MORE: Van de Vorst family upset Catherine McKay sent to healing lodge

However, other research has reflected more positive rates for repeat offenders.

Recidivism rates cited in a 2016 paper out of Northern Arizona University (NAU) showed that, of 286 healing lodge residents who had been released from three facilities, “six per cent had reoffended while on conditional release which compares to the federal recidivism rate of 11 per cent.”

That paper also noted that the recidivism finding in the CSC’s 2002 study was updated in an evaluation of healing lodges that it conducted in 2011.

That evaluation found that conditional releases for Indigenous offenders from healing lodges were “as likely to be maintained in the community as conditional releases for aboriginal offenders from minimum security institutions for men and multi-level security institutions for women.”

“This is quite a respectable result considering that healing lodges are more likely to get offenders at higher risk of reoffending than regular minimum-security institutions,” wrote author Marianne Nielsen.

Deeper understanding

The potential to re-offend is but one measure by which to evaluate healing lodges’ effectiveness.

They can also be measured by the positive changes in their residents.

The CSC’s 2011 evaluation of healing lodges found “statistically significant” changes on numerous levels.

Offenders at healing lodges showed an increased familiarity with Indigenous traditions and teachings.

Before being incarcerated, about one-third of these offenders showed they were “moderately familiar” or “very familiar” with such teachings; that figure rose to two-thirds after entering healing lodges.

They also reported stronger familiarity with Indigenous history and traditional languages.

“Overall, results suggested that healing lodges had a positive impact on offenders’ knowledge of, and connection, to aboriginal culture,” the study said.

READ MORE: What to know about healing lodges, where Tori Stafford’s killer is serving her sentence

Offenders chalked up these improvements to engagement with elders.

Residents likewise reported a stronger understanding of themselves — their lives, their offences and their circumstances, the 2011 study said.

They felt deeper senses of accountability and responsibility, and they said they were more comfortable communicating with other people.

They also reported better self-control, especially as related to their emotions.

Ultimately, researchers found that “culturally-appropriate environments can contribute to the healing process of the offenders.”

Residents find themselves in environments where they can engage directly with elders, in environments that are “more conducive to building respect and positive relationships.”

Controversy will persist over those chosen to reside at these lodges.

Nevertheless, a significant body of research shows how they can heal.

Comments