Montreal — it’s a city whose median incomes rank with the lowest in Canada and the U.S.

It’s also the only one of Canada’s three biggest cities not yet afflicted by a housing crisis — through prices are growing.

In June, you could still buy a single-detached home there for just over $325,000 — in Vancouver, that kind of house would likely go for closer to $1.5 million.

Coverage of Montreal real estate on Globalnews.ca:

Unlike Toronto or Vancouver, Montreal is a city where home prices still appear to be attached to people’s incomes. And they’re growing at close to 10 per cent annually amid solid economic returns.

Montreal’s earnings were just one piece of data that formed part of a study released by Simon Fraser University’s City Program on Friday — and they come at a time of, not just home price growth, but when international buyers appear to be taking a growing interest in Quebec’s biggest city.

This chart shows an affordability index for 25 cities in Canada and the U.S. The numbers displayed means people have to work that many years on median incomes in those cities to afford median-priced homes there — Montreal ranks fifth-lowest (click to enlarge):

The data was complied by City Program director Andy Yan, using info from Canada’s 2016 Census as well as the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2016 American Community Survey.

The study covered metropolitan areas with populations of 500,000 people or more — in Montreal’s case, that would include not just the city, but Laval, Terrebonne and Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu.

Of the 117 cities he looked at, he found that, at $61,790, Montreal’s median incomes ranked in 89th place.

That was lower than any Canadian metropolitan area and indeed, most U.S. metros as well. It came up just behind Ohio’s Cleveland-Elyria region ($62,061) and Alabama’s Birmingham-Hoover area ($62,174).

Montreal’s median income represented growth of just under 40 per cent from 2011, when it was $44,157.

Get daily National news

The city’s ranking on median income didn’t necessarily match its place when it came to affordability, however.

Yan took median housing values and compared them against median household incomes and he found that Montreal’s ratio was 4.9 — suggesting you would need to earn a median income for 4.9 years to afford a median-priced home.

That was good enough for Montreal to rank 21st in Canada and the U.S., tying it with Fresno, Calif., and Colorado’s Denver-Aurora-Lakewood region — and rank it close to cities such as Portland, Seattle and Boston, all of which had a ratio of 5.0.

READ MORE: Montreal area real estate market growth outpaced other Canadian cities in May

“Montreal is Canada’s Portland,” Yan joked, noting a similar affordability ratio (5.0) in Oregon’s biggest city.

Yan was surprised to see Montreal rank so low when it came to incomes, but its index, he noted, suggested that home prices were pretty closely tied to its incomes — especially in contrast with Vancouver, where the affordability ratio was 11.0, and Toronto, where the ratio was 8.3.

Desjardins economist Helene Begin was less surprised with Montreal’s low ranking on incomes, however.

She said the city’s low incomes are a function of its low cost of living, noting that the average home price was $378,000 in the first quarter of the year — and that means Montrealers have stronger purchasing power than they might in Canada’s two other biggest cities.

Incomes are low for a number of reasons — one of them is that the province of Quebec saw as much as 16 years in which its economic growth was lower than other parts of Canada, and the jobless rate was higher than elsewhere, Begin said.

Now, however, wages are increasing as various industries grow, the high-tech industry in particular.

“New companies are seeing Montreal as a high-tech city, like multimedia, video games, artificial intelligence,” she told Global News.

She said warehousing is also a robust industry, with distribution centres that are expanding.

This growth is enough to help power a housing market now seeing the kinds of gains it hasn’t seen since the early 2000s, Begin said.

Home prices on the Island of Montreal grew by close to 10 per cent in each of the last three months, according to the Greater Montreal Real Estate Board (GMREB).

That’s faster than they’ve grown in the past two years, and the kind of price growth the city hasn’t seen in almost two decades, Begin added.

Realty firm Royal LePage noted this week that home price growth in the Greater Montreal Area surpassed Canada’s national average for the first time in seven years in the second quarter, growing at 5.9 per cent.

READ MORE: Could you pass the mortgage stress test? Here’s how to find out

Home price growth has been strong enough to withstand more stringent housing regulations at the federal level, with the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada (OSFI) introducing a new stress test for uninsured mortgages.

Implemented in January, the stress test appears to have had little effect on Montreal real estate, which set a sales record in May.

That’s because mortgage lenders such as Desjardins, which holds almost 40 per cent of the market, already set stricter standards for borrowers, according to Begin.

She said housing is likely to cool off with lower economic growth expected this year, but even if home prices were to keep increasing at 10 per cent, she thinks the market would be able to absorb them.

Foreign interests

All this growth comes as Montreal housing appears to be attracting more interest from abroad.

Property portal Juwai.com reported this month that Chinese inquiries into Quebec property have grown in each of the last two years, by 66.4 per cent in 2016 and by 37.6 per cent in 2017.

Most of these inquiries were interested in buying property for their own use (56.2 per cent), while 26.3 per cent were looking to use homes as investments.

Begin admitted that foreign buyers could be emerging as a factor in Montreal real estate, but she said it’s “not the main driver” of price increases.

“Price increases are driven by Quebecers that are living here,” she said.

She pointed to statistics released by the Quebec government that show foreign buyers make up 1.4 per cent of sales in the Montreal region in 2017.

That’s compared to 3.5 per cent in the Vancouver region — although a study of non-resident buyers, which includes foreign purchasers, showed a much higher share of non-resident buyers when you looked at West Coast data by area, housing type and period of construction.

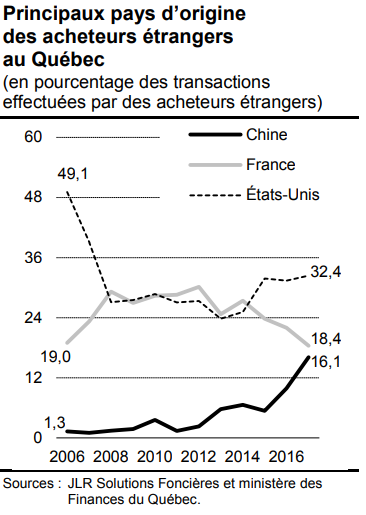

The Quebec government’s statistics also showed increasing interest from China in the province’s housing.

Of the foreign buyers who purchased property in Quebec in 2017, the greatest share came from the United States (32.4 per cent), followed by France (18.4 per cent) and China (16.1 per cent).

But sales to buyers from China also grew the most since 2006, from 13 sales at that time to 212 sales in 2017 — representing a growth in its share of sales of just under 15 per cent in that timeframe.

By contrast, the share of buyers from the United States dropped by just under 17 per cent, and French buyers by 0.6 per cent.

Begin admitted that Chinese buyers are more active in the market than they used to be, but she said it’s still “not a big part of the market, even if there are more there.”

“It just adds speed to the market a little bit, and it’s still not the main factor,” she said.

Of course, foreign-buyer data alone isn’t likely to capture the full influence of international capital on a housing market.

Foreign residents who wish to come to Canada can do so through the Quebec Immigrant Investor Program (QIIP), an initiative that was previously criticized for acting as a springboard for wealthy immigrants into Vancouver and Toronto real estate and played a role in driving up home prices.

The program, which tends to attract people who love to invest in real estate, offers permanent residency to applicants after they make an interest-free investment of $1.2 million with the provincial government, that’s returned to them after five years; once a permanent resident, you’re no longer a foreign buyer.

Quebec has changed the program’s rules in order to combat the springboard effect, making it so that applicants are likely to be rejected if they have relatives outside the province, if their children are going to school somewhere else in Canada, or if they have owned any Canadian property in a place other than la belle province.

The aim, it appears, is to motivate wealthy immigrants to move to Quebec and stay there; but the outcomes of that policy change have yet to be evaluated.

Comments