A life-and-death battle against drug dealers is being waged on the sprawling Blood reserve in southwestern Alberta, as officials struggle to keep deadly opioids away from its most vulnerable residents.

Canada’s largest reserve has been on the front lines of a fentanyl epidemic that has plagued many parts of the country over the last four years.

READ MORE: Drug ‘dementors’ stalk fentanyl addicts in Alberta amid western crisis

Fentanyl, an opioid up to 100 times more powerful than heroin, is used as a painkiller for terminal cancer patients. But on the streets, the drug — also known as “beans” — emerged as an OxyContin replacement after that drug’s formula was changed.

Sixteen overdose deaths in the first three months of 2015 prompted the Blood band, which has about 10,000 members, to declare a state of emergency.

READ MORE: Albertans continue to die in large numbers from fentanyl use

A second state of emergency was called after a rash of overdoses at the end of February when a batch of carfentanil, described as 100 times more toxic than fentanyl, hit the community.

“We were ill-prepared for it. EMS and the police had horrendous calls,” said Dr. Esther Tailfeathers, who was born and raised on the reserve.

“They’d come to a house and there would be five people who had overdosed and they were unresponsive and not breathing. In that weekend, we had 14 overdoses and luckily no one died.”

There were another 50 overdoses in Lethbridge that weekend.

READ MORE: Lethbridge emergency crews called to 42 drug overdoses in 1 week

“We haven’t seen another night like that,” Tailfeathers said. “But I’m sure it’s not the last night we’re going to see something like that.”

Get weekly health news

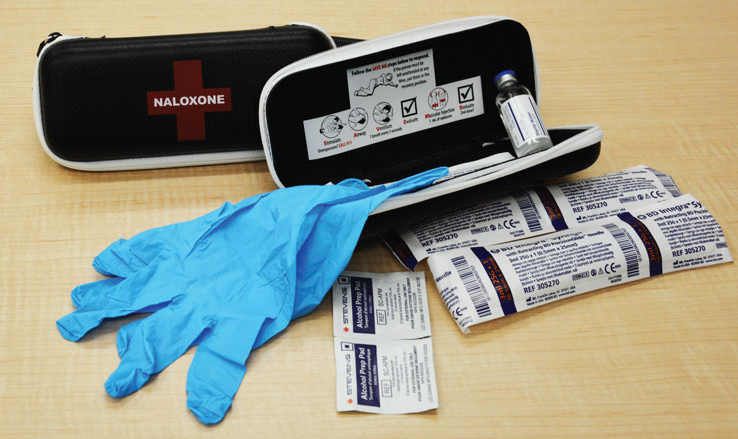

Tailfeathers said progress has been made with the introduction of naloxone and Suboxone, a non-addictive medication used to treat opioid addiction.

But drugs are still making their way onto the reserve and, she said, dealers seem to know exactly when to strike.

“There are certain days when we’re going to see more overdoses, more violence related to drug dealing and more suicide attempts,” she said.

“Those are always related to a payment in the community — a day after welfare comes out or a day after child tax benefits, even (Assured Income for the Severely Handicapped) and Canada Pension.”

Blood Tribe Police Chief Kyle Melting Tallow said several dealers have been banished only to set up shop in communities on the edge of the reserve. He said they find drug mules, usually addicted band members, to carry fentanyl onto the First Nation and sell it when cash is available.

“They know when the money is in the community, so that’s when we see the trafficking go up in frequency.”

READ MORE: Three people charged in two drug overdose deaths on Alberta reserve

Addictions have been a problem for the Blood Tribe for generations.

“We do have a lot of addicted people. We do have a lot of people who are in vulnerable situations and some of them don’t know how to deal with certain things,” said Melting Tallow.

“We have dealers who come in from outside the community and take advantage of that.”

The CEO of the Blood Tribe Department of Health said additional community health staff, a harm reduction nurse and a crisis prevention team have been added.

But despite increased awareness, some people are still getting “tricked” by whatever they’re buying, said Kevin Cowan.

“If it’s not fentanyl, it’s going to be something else. The drug addiction, the alcoholism, it all continues to happen,” said Cowan.

“We’re just saving lives now because of naloxone. Whereas two or three years ago, it wouldn’t have been 50 plus overdoses. It would have been 50 plus deaths.”

READ MORE: Fentanyl a growing concern for law enforcement as Alberta peace officer exposed to deadly opioid

Rick Tailfeathers, a spokesman for the Blood Tribe, said the band is looking at mixing up the timing of payments to members so they don’t all happen on the same day.

“We’ve lost a lot of people through overdose fatalities. It was OK after 2015 — things improved and the overdoses were way down. But they’re back.”

He said the current addictions are more deadly than those in the past.

“There was alcoholism that was rampant in the ’60s. But today you hear almost daily about overdoses and it’s fatal. That didn’t happen until just recently — I would say in the last four years,” Tailfeathers said.

“I don’t see any end in sight as long the addiction is there. Fentanyl is highly addictive and most drug users are going to try and find it. It’s the big guys, the dealers, that need to be caught.”

READ MORE: Canadian drug policy expert says it’s time to legalize all drugs

- Something’s fishy: 1 in 5 seafood products are mislabelled, study finds

- After controversial directive, Quebec now says anglophones have right to English health services

- Why non-alcoholic beer is gaining steam at Oktoberfest: ‘Nobody will judge you’

- Recall expands for Nutrabolics vegan bars over undeclared milk

Comments