The Trudeau government is standing by its pledge to eradicate all drinking water advisories on First Nations by March 2021, but for some engineering experts, there is a healthy feeling of skepticism this promise will be kept.

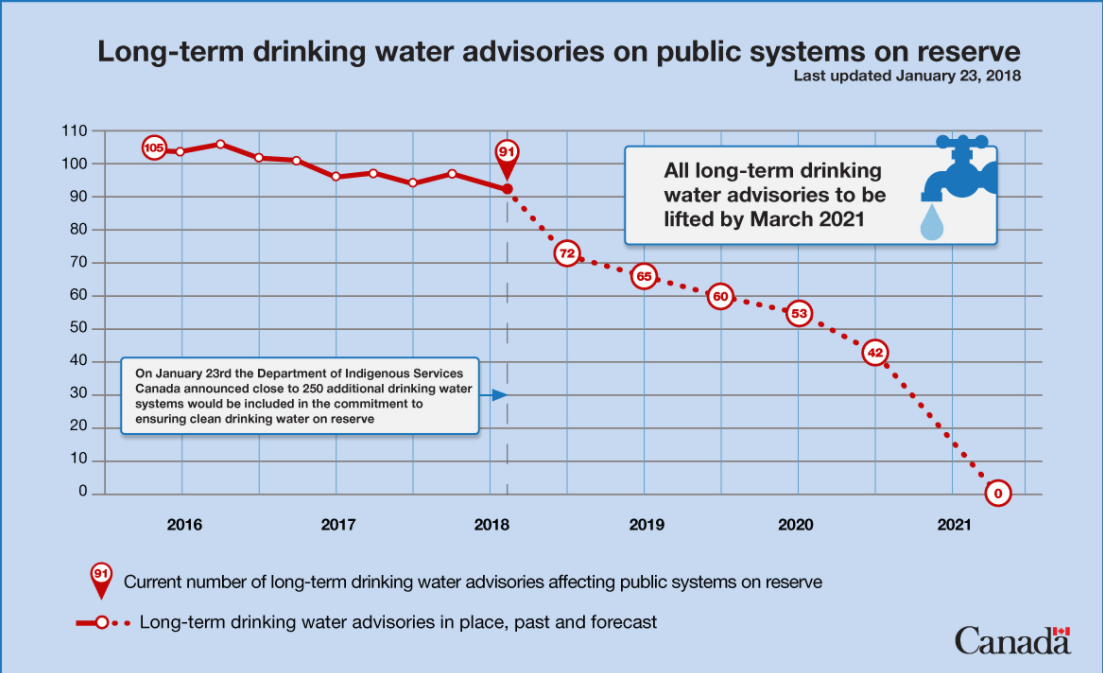

On Tuesday, Indigenous Services Minister Jane Philpott announced the list of long-term advisories now stands at 91 – up from 67 – as an additional 250 drinking water systems would now be eligible for public funds. More than 1,000 drinking water systems will now eligible for support from Indigenous Services Canada.

READ MORE: First Nations ‘living in Third World conditions’ as communities endure water advisories

“I want to reiterate that the deputy and I have been very clear with the department. We must get this done. We are firm on the commitment that the prime minister has made and we will get the work done,” Philpott told reporters at a press conference Tuesday.

Craig Baker, general manager of First Nations Engineering Services Ltd. of Ohsweken, Ont., has worked with First Nations communities across Canada to build and design water treatment systems.

READ MORE: Jane Philpott says political will is there to solve child welfare crisis for Indigenous kids

He has heard the promises from Ottawa but says that unless there is a dramatic change in the flow of funding to Indigenous communities, the 2021 goal won’t be met.

“If you leave the capital project process in the hands of the Department of Indian Affairs, it will be very difficult to obtain that goal,” Baker told Global News. “It’s the worst run capital program in Canada. It’s all been designed to slow things down because we don’t have enough money to fix all the needs, so they create layers of bureaucracy that make it very, very difficult to get projects approved.

“We take more time to get a water treatment plan approved through their system than to build it, which is insanity,” he said.

Baker said in addition to red-tape, the water crisis facing First Nations communities is exacerbated by treatment facilities that aren’t designed to meet the needs of expanding communities, a lack of training for operators, and temporary fixes or upgrades to outdated infrastructure.

“It’s unconscionable that our aboriginal people do not have the same level of infrastructure in their communities as the rest of us do,” he said. “We all have the same expectation when we turn on a water tap, no excuses.”

Philpott has acknowledged her department will roll out funds faster to communities as the government attempts to hit its projections of 65 advisories by 2019, 53 by 2020 and 0 by 2021.

The struggle to provide clean drinking for all First Nations communities has been a black eye for Canada for decades. Forty communities across Canada have been dealing with drinking water advisories for a decade or more with the longest-standing boil water advisory being in the Neskantaga First Nation in northern Ontario, which hasn’t had clean drinking water since 1995.

Get daily National news

WATCH: Human Rights Watch calls out Canada over First Nations water crisis

Gull Bay is home to roughly 300 people near the shores of Lake Nipigon. The small reserve received a new water treatment plant – completed in 2002 – after the deaths of two band members, which were attributed to drinking water in 1998.

Chief Wilfred King estimated Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) spent between $10 million and $20 million on the plant, but it has never worked properly.

“We’ve been under a water boil advisory for an awfully long time,” King told Global News. “And it hasn’t been good for Gull Bay.”

The community relies on drinking bottled water and uses a water system from the 1970s for laundry and bathing.

King said there were several issues with the plant. Significant technical skills were required to operate the plant, chemicals had to be shipped hundreds of kilometres for disposal, and the engineering firm behind the project had no experience with water-treatment plants.

“It couldn’t produce potable water,” he said.

Yet King is optimistic the federal government will keep its promise. He said the federal government, as recently as December, assured him that Gull Bay is a “priority.”

“They’ve committed to ending the boil water advisory,” he said. “I think the commitment is sincere…. But if this was a non-native community the problem would have fixed a long time ago.”

Funding gap on First Nations water promise

A report from the Parliamentary Budget Officer (PBO) in December warned that the federal government was spending only 70 per cent of what is needed to end boil water advisories

Charlie Angus, the NDP’s Indigenous affairs critic, said at the time the report shows the Liberal government hasn’t invested enough money to meet Trudeau’s promise.

- Elections Canada to recommend tighter nomination rules after foreign influence probe

- Nearly 13K international students applied for asylum this year, data shows

- Auto fraud is up 54% in Canada — and culprits may not be who you think

- The Bank of Canada is ‘scaling down’ plans for a possible digital loonie

“Access to clean water is a fundamental right,” Angus said. “It is time the government got serious about this.”

READ MORE: Many First Nations communities without access to clean drinking water

Philpott said a majority of the $2 billion allocated to address water systems in Budget 2016 remains unspent and there is potentially another $4 billion that is allocated to Indigenous infrastructure projects that could be used.

Madjid Mohseni, scientific director at Reseau WaterNet, a partnership that works with small communities to provide drinkable water, said funding alone is not the solution. He said the issue of water boil advisories will continue across Canada unless First Nations communities are brought into more decision-making processes.

“You can spend millions of dollars on a system and it could fail within a month or a year because they don’t like it or they don’t know how to operate it,” said Mohseni, who is also an engineering professor at the University of British Columbia. “First Nations need to be at the table when there is a discussion on what should be the approach and what should be the solution.”

Water treatment issues in First Nations communities are complex and each situation is different from a technical point of he said.

Remote First Nations communities will often have to fly in engineers to fix any problems with delays leading to greater damage to infrastructure.

“If there is no operator on site to operate the system, the system is going to fail,” he said. “There needs to be a long-term investment in terms of training and educating.”

WATCH: First Nations fighting for what we all take for granted—clean drinking water.

Lysane Bolduc, an engineer with Indigenous Services Canada, says the government has worked to streamline the process of approving projects like water filtration systems.

“The level approval – internal to our department – for capital projects was raised significantly from a threshold of $10 million to $15 million for regional approval as opposed to headquarters approval,” Bolduc said.

Bolduc said the department continues to provide support for the Circuit Rider Training Program, which provides First Nation operators with hands-on training on how to operate and maintain the water and wastewater systems in their community.

“These are historic, long-term investments. We are talking about $1.8 billion over five years,” she said. “This is longer than any previous targeted program available to First Nations.”

As for whether Ottawa will meet its 2021 goal, Mohseni and Baker remain skeptical.

“A lot of things have to fall into place,” Baker said. “History says they won’t fall into place with the bureaucracy that’s there.”

*With a file from the Canadian Press

Comments