With devastation wrought by habitat loss, climate change, pollution and overfishing, new research suggests that as much as half of the wildlife in Canada could be dying off at alarming rates.

A total of 451 species in decline — roughly half of the total mammals, birds, fish, reptiles and amphibians studied as part of the World Wildlife Fund Canada’s Living Index, to be released Thursday — saw their population decline by an average of 83 per cent between 1970 and 2014.

Worse yet, following the 2002 implementation of the Species at Risk Act, many animals afforded protection under the federal conservation law have died off faster than they had before. The 64 species under SARA protection covered in the new research saw their population decline by an average of 28 per cent, or 2.7 per cent per year, from 2002 to 2014 — up from a 1.7 per cent annual average from 1970 to 2002.

The report is likely the most comprehensive of its kind ever conducted in Canada, and looked at some 3,689 different populations of 386 kinds of birds, 365 fish species, 106 different mammals and 46 reptiles and amphibians.

It paints a grave picture and raises questions about the effectiveness of the Canadian government’s efforts to curtail wildlife losses, about the heightened impact of industry and climate change on dwindling populations, and about the future ecology of the world’s second largest country.

“I hope that people say this is really sobering,” said David Miller, WWF Canada’s CEO, in an interview with Global News.

- What is B.C.’s Mental Health Act and why is it relevant to Tumbler Ridge shooting?

- YouTube, Roblox say they deleted accounts tied to Tumbler Ridge shooter

- Elections Canada says Freeland broke rule by answering byelection questions

- Air Canada says it saw strong profits despite drop in U.S. travel demand

“That people say, ‘we had no idea that half of the wildlife in Canada was declining so rapidly and we want to do something about it.'”

What’s threatening Canada’s wildlife?

According to the index, habitat loss is the greatest threat to wildlife, impacting species such as the endangered woodland caribou, a national symbol that appears on the tails side of the Canadian quarter. In 2011, there was only an estimated 34,000 left across Canada.

Nearly 216,000 square kilometres of forests in Canada were disturbed or fragmented from 2000 to 2013, causing significant roadblocks to population stability among dependent animals.

Get breaking National news

And with Canada warming at twice the global average, shifting seasons and temperatures caused by climate change are an emerging threat. For example, Canada is host to 90 per cent of the world’s narwhal population in the summer months, and the report names the famously tusked whales — of which there are about 50,000 — “the most vulnerable of all Arctic marine mammals” because the icy waters they live and hunt in are becoming increasingly scarce.

Other contributors to population loss included pollution, the introduction of invasive species and the overexploitation such as commercial fishing.

READ MORE: These five species could disappear from Canada

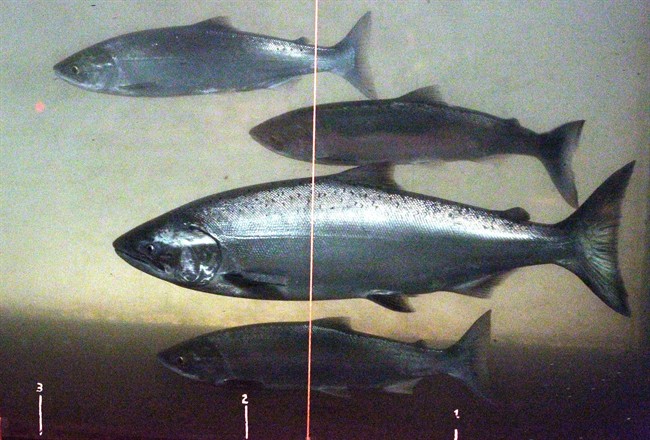

Many population declines are related and can be attributed to multiple causes. In British Columbia, chinook salmon populations that were once devastated by overfishing are now threatened by hydroelectric dams and reservoirs. As their numbers have dwindled, so have southern resident killer whales — only 78 of the smallest orca population in the Northern Pacific ocean, which feeds primarily on chinook salmon, remain as of July 2017.

“If we continue to see a really significant decline in wildlife populations, whether it’s in the ocean or on land, they’ll be a risk to us,” said Miller.

“Whether it’s immediate ones, like if there’s a decline in fish populations, we’re going to have trouble fishing and eating, or a longer term one is we see a decline in populations that could, over time, affect our ability to survive on the planet.”

What needs to be done?

While Miller said the hope is that conservation efforts should avoid species ever having to get there in the first place, WWF-Canada’s report highlights what researchers say are several key shortcomings in the federal government’s conservation efforts through the Species at Risk Act: repeated delays to get animals listed on SARA, failures to meet the Act’s timelines for recovery strategies and identifying and protecting critical habitat, deference to socioeconomic considerations such as commercial fishing and a lack of adequate funding for recovery plans.

“The Act and the processes under it haven’t had the effect that was hoped, which is reversing the decline of wildlife populations,” said Miller. “We also think we need to think about an ecosystem approach, because what’s happening to an entire ecosystem, whether it’s pollution or loss of habitat or climate change, affects multiple species including the ones that are in decline. And that approach isn’t really facilitated through the current language of the act.”

The report is not all bad news, as half of the species studied saw their numbers increase to some degree. According to the report, successes have occurred where problems were more quickly identified and addressed, such as the banning of DDT which has helped the populations of raptor birds like the falcon. Although often, it’s simply species that are able to adapt to human beings and habitat change, like Canada geese, whose populations thrive.

Despite concerns, Canada still outperforms the world at large

And, while many at-risk wildlife populations in Canada are in freefall, overall the country is ahead of the rest of the world in terms of species conservation.

“The good news is that relative to countries worldwide Canada is actually going pretty well,” said Sarah Otto, a professor of biology at the University of British Columbia and director of its Biodiversity Research Centre. “World wide, there has actually been 50 per cent declines in the number of individuals within most vertebrate populations.”

Taking into account all 903 species WWF-Canada studied, the total number decreased by eight per cent over the 44 years studied.

Otto said Canada’s populations are healthier on a global scale in part because the country has vast expanses of wilderness and a relatively small human population.

However, Otto agrees that the pace of decline among species at risk, particularly those protected by SARA, is of serious concern.

“In the last decade, the Species at Risk Act was ineffectual,” she added. “Until the new government there had really only been nine species of the hundreds we know to be at risk who had gone through the whole process to be protected.”

Nevertheless, Otto said the Trudeau government under Environment Minister Catherine McKenna has made some progress on the file.

“The new government has really racheted up the speed with which it’s trying to get through listing species and figuring out how to protect them,” she said. “But it’s coming very late and we’re not yet seeing that actually improving the status of species at risk.”

She also said that, while there is hope that the report could spurn action by people, industry and governments, rough days are ahead.

“We are going to lose species. We are going to lose ecosystems. We’re going to lose precious natural spaces, but if we don’t act we’re going to lose a lot more. I think the hope is really important that we only act when we believe we can do something, and I think Canada’s biodiversity and natural wild life is precious. The more hopeful we are that everything we do can save species, the more it will be worth it.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.