In late 2015, the newly-elected Liberal government announced an ambitious plan to get 25,000 Syrian refugees onto Canadian soil in the span of just a few months.

Some — the most vulnerable and least educated — would be government sponsored, while others would rely on individuals or groups of Canadians to help get them here and assist them as they adjusted to life in Canada.

It was an enormous and complex undertaking, but hardly an unprecedented one.

For centuries, Canada has opened its doors to the displaced, the persecuted, the hunted, the starving and the politically oppressed.

We can trace our reputation as a safe haven to the 1700s and the first Loyalists who came north during the American Revolution.

In time, thousands of black American slaves would also make the treacherous journey to freedom along what became known as the Underground Railroad.

READ MORE: Could you pass the Canadian citizenship test?

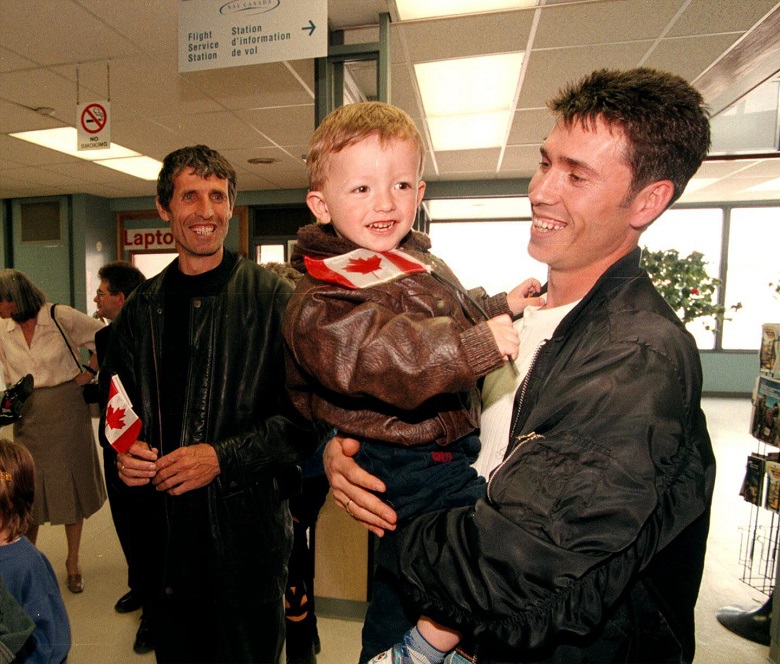

Over the next two centuries, Polish, Italian, Jewish, Ukrainian, Irish, Scottish, Hungarian, Kosovan, Chinese, Vietnamese, North African, and most recently Syrian refugees poured in by the hundreds of thousands. They have become part of the fabric of our country, now one of the most diverse on Earth.

“We have had well over 200 years of practice at this,” said Stephanie Bangarth, an associate professor of history at King’s University College, part of the University of Western Ontario.

“This is, in fact, what has made Canada. This movement of refugees, of people in need, fleeing persecution and coming here to this place … this is as much a part of our history as anything else.”

Get breaking National news

But while Canadians may rightly pride themselves on that history, Bangarth said it’s important to remember that we are a settler nation that originally displaced Indigenous Peoples, and that our story has subsequently included more than a few dark chapters.

WATCH: Exploring your Canadian roots during Canada 150

Canada has often selected only “the cream of the crop” of refugees for economic gain, explained Bangarth, herself the daughter and granddaughter of first-generation Hungarian immigrants.

“(We’ve) maybe not always taken the neediest,” she noted.

“We’ve managed to perhaps avoid some of the more challenging aspects of refugee reception, such as what’s happening currently in Europe.”

Deeply ingrained racial and political prejudice have also informed the government’s choices about who to admit in the past, and who to turn away.

READ MORE: Canada’s strangest laws, from witchcraft to blasphemy to sleigh bells

Canada infamously allowed only a few thousand displaced Jews into the country at the height of Nazi terror in Europe. One unnamed Canadian official was quoted as saying that when it came to Jewish refugees, “none is too many.”

Communists have also found the door to Canada shut tight.

“In 1973-74 there was a big coup d’état in Chile … and the Canadian government was very slow to respond in taking in the left-wing activists who were being persecuted by General Pinochet’s’ military government,” Bangarth said.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau recently apologized formally in the House of Commons for an even earlier failure: the Komagata Maru incident of 1914, in which more than 350 Sikhs were denied entry to Canada by the government and sent back across the Pacific Ocean — some to their deaths.

Still, Bangarth noted, when successive governments have been reluctant to act, Canadians themselves have often stepped up and insisted on helping.

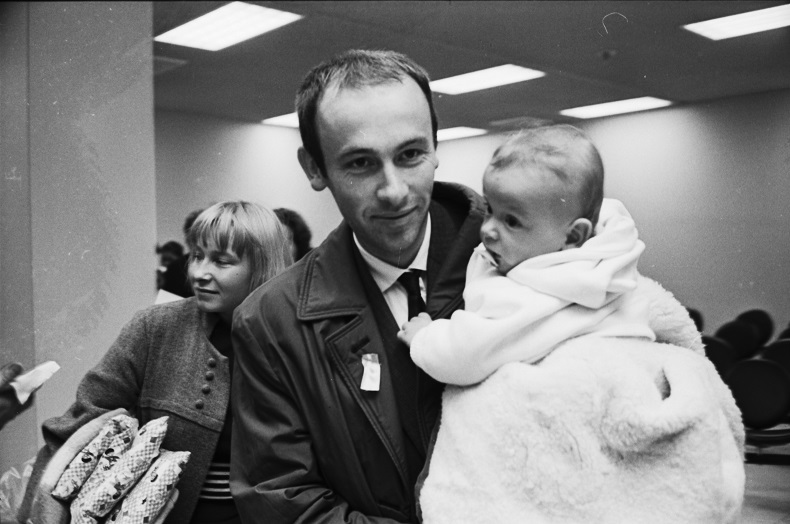

The recent Syrian refugee crisis and the arrival of 60,000 Vietnamese “boat people” in the late 1970s are good examples of how a groundswell of popular support can make welcoming thousands of people in a short period possible, she noted.

WATCH: Young Syrian refugees get warm welcome from elementary students

In 1986, the United Nations High Commission on Refugees awarded the Nansen Medal to the Canadian people, in recognition of outstanding service to the cause of refugees, displaced or stateless persons.

“Canadians in general are becoming aware of their place in the world and our responsibility as a global citizens,” said Bangarth.

“The increasing sensitivity to respond to refugee issues, it comes out of that, rather than history, unfortunately. And I say that as a historian.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.