Tara Finnessy got off fentanyl two years ago.

Before then, the Ottawa woman had been an off-and-on user since her fiancé’s accidental death in 1999. “I was in pain and I wanted to not be in pain. That’s how I started my journey with fentanyl,” she said.

She had been prescribed other opioids in the past, but very quickly turned to fentanyl, drawn to its potency.

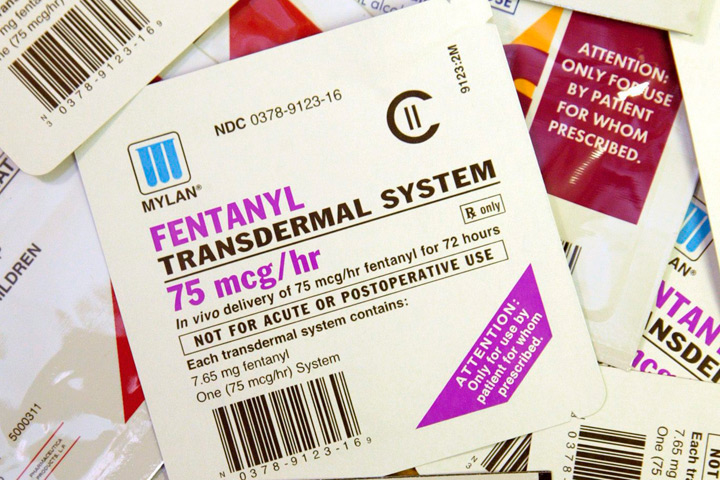

“The fentanyl was everywhere and it was cheap at that time,” she said. “There were people getting prescriptions who didn’t quite know the street value of this drug. So I was able to obtain like 100 microgram patches for like $5. It was crazy. It was just crazy.”

If used as prescribed, one transdermal patch might last a patient 72 hours. Finnessy was using about one a day, she said, chewing it or extracting the drug and injecting it for a faster high.

Now she’s on methadone therapy and helping in outreach programs for other drug users. And from them, she’s hearing even more about fentanyl now than before – particularly the new form that’s causing so many deaths in Western Canada: powdered fentanyl.

“It’s readily available now,” she said. “Just a phone call.”

Powdered fentanyl is a relatively new arrival to the nation’s capital, and it has local health authorities and outreach workers worried.

Thirteen years ago, Ottawa had 100 emergency room visits from unintentional drug overdoses. In 2015 it was 205 — something Ottawa Public Health attributes partly to fentanyl.

Newly released numbers from British Columbia show the problem is much worse there than in Ontario: 488 people have died so far this year from drug overdoses. Unfortunately we can’t really compare Ontario to B.C., as the most recent mortality numbers available are from 2015 — something that policy workers say is inadequate to keep up with a rapidly changing environment.

And they’re taking this problem seriously.

Rob Boyd, who has worked for years as the director of OASIS, a harm reduction and needle exchange program in downtown Ottawa, says he tries not to be alarmist about reports of new drugs. Fentanyl is different.

“Powdered fentanyl scares me. A lot.”

Building a public health crisis

According to Boyd, and as Global News has reported since 2013, the opioid addiction problem has been building in Canada for decades, and much of it started with prescription medication.

“Fundamentally the problem is that the benefits of prescribing opioids was oversold and the harms associated with opioids was undersold,” said Boyd.

Opioid painkillers, in particular OxyContin, were over-prescribed, he said, so a large group of people from a variety of socioeconomic groups developed a dependency on the drug. Some they used themselves, and some they sold to others, who also became dependent.

Then in 2012, OxyContin was taken off the market — replaced with a tamper-proof version that was harder to crush up and inject for an instant high.

“In response what happened was an increase in people being prescribed and seeking fentanyl,” said Dan Werb, an assistant professor of public health at the University of California San Diego, and director of the International Centre for Science in Drug Policy.

People didn’t suddenly stop using, said Boyd. “Of course they didn’t stop using drugs. They were dependent on them. So they moved to other drugs.”

Then, as the dangers of prescription fentanyl — a much more powerful drug than OxyContin — became clear, doctors became more reluctant to prescribe it, said Werb.

“If the pharmaceutical market is no longer going to supply people who are now opioid-dependent, the illegal market is going to.”

Hence illicit fentanyl: a powerful, powdered form of the drug. According to Calgary police Staff-Sgt. Martin Schiavetta, powdered fentanyl offers criminals several advantages. It can be bought cheaply overseas and online. It’s easy to transport – since it only takes the tiniest amount to have an effect, it’s compact and can be sent undetected through the mail. It can be synthesized here from precursor chemicals, or mixed with talcum powder and pressed into pills, to be sold at huge profit.

“Moving from oxycontin to fentanyl is bad enough,” said Werb. “But once you move from prescribed, dose-based fentanyl, where you know exactly how much is in there, to the illegal fentanyl that is being shipped in from places like China and mixed with other drugs, that’s when things get really, really dangerous.”

Every pill, even from the same batch, could be of a different strength — from having almost no effect to potentially life-threatening.

Werb puts the blame squarely on Canada’s drug policies. “It’s not like there is a crisis because this new drug has emerged. It’s the result of very explicit policy changes that have sought to reduce harms and have actually in many ways increased harms.”

Appearance in Ottawa

“When I first heard about fentanyl, maybe two years ago, it was all about patches and how people were breaking down patches,” said Catherine Hacksel, who works with the Drug Users Advocacy League and runs a drop-in program for drug users.

Fentanyl was prescribed as a skin patch. When sold illegally, it might be cut into pieces — a half, or quarter patch that was chewed, or melted to extract and inject the drug, or burned and inhaled. The worry at the time was that the drug wasn’t evenly distributed throughout the patch: half a patch didn’t necessary mean half the dose, she said.

Hacksel says fentanyl patches are still being used, but powdered fentanyl is entering the scene.

“We have seen an increase in reported use and availability of powdered fentanyl here in Ottawa,” confirmed Kira Mandryk, supervisor of Ottawa Public Health’s harm reduction program. It’s been in Ottawa for over a year, and in the last few months, they’ve heard more reports of it from clients.

“We’ve also had clients tell us that they’re using drugs that they don’t know are cut or containing fentanyl, which increases their risk of overdose, which is quite concerning,” she said.

“It’s definitely had an impact in terms of overdose.”

READ MORE: Police, community groups warn fentanyl crisis looming in Ontario

Fennessy said that fentanyl has a definite appeal over other opioids, and more people are turning to it for that reason. “It’s worth their money to buy fentanyl. You feel like you’re getting your money’s worth. It’s strong.”

And it’s strong enough that many people don’t consider the risks when they take it. They believe an overdose won’t happen to them, she said, or they don’t care if it does. “When people have to make the decision, do I not use this because it could possibly kill me, or if I don’t use it, I’m going to feel like I want to die because I’m going to be so sick. So when people have to weigh it, they take the chance. Anything not to feel like death.”

READ MORE: Fentanyl overdose paralyzes Calgary teen: ‘he has a life sentence now’

But fentanyl overdoses so far in Ottawa haven’t yet hit the crisis levels seen in B.C. And things even worse than fentanyl, like the vastly more powerful carfentanyl, could arrive soon too, thinks Boyd.

“These drugs are all around us in the northeast U.S. states, they are out west. There’s no reason to believe that we’re not facing these drugs,” he said.

And it’s the most vulnerable who are getting hurt, said Hacksel. Basic drug safety precautions include things like knowing the source of the drug (something that’s harder given powdered fentanyl’s variability), and taking it in a safe space with other people around, she said.

“Those are things that require consistency. But if you’re on the street or maybe more transient, you’re going from one city to another, that consistency is not as available which makes it even more unsafe. The only consistent thing is the fact that you need the drug.”

She doesn’t think banning drugs is a good solution when someone is dependent.

“The reality is people will go to the end of the earth if they’re addicted.”

For now, Hacksel, Boyd and Mandryk are all taking a similar approach: educating people about safer drug use, distributing and training people in the use of the opioid overdose antidote naloxone, pushing to open Ottawa’s first supervised injection site — all in hopes of reducing the number of overdoses and preventing B.C.’s emergency from coming to their city.

Boyd would like to see the approach change more fundamentally. “Our typical response to drugs is to ban them and to prohibit their use,” he said. “The problem with that, and we’ve been doing it for the last 50 years is that drugs are more available, there’s more variety, they’re cheaper and they’re more lethal than ever before.

“We do need to step back and we need to say, ‘Is what we’re doing the correct way of dealing with this issue?’ I think that it’s pretty clear that the answer is no.”

NEXT WEEK: How other countries are combatting addiction

Have you had an experience with synthetic fentanyl? Tell us your story using the form below.

Note: We may use your response in this or other stories. While we may contact you to follow up we won’t publish your contact info.

Comments