TORONTO – For years — decades, actually — Noreen Smith couldn’t perform the simple actions of everyday living that most of us take for granted: drinking a cup of coffee; writing her name; styling her hair.

Her dominant right hand would shake so violently that she had to try steadying it with her left or have her husband help with whatever task she was attempting. Her passion — drawing quick-sketch portraits of people — had become impossible.

READ MORE: Brain surgery eliminates tremors for B.C. resident with multiple sclerosis

The couple’s social life contracted, with Smith ending up virtually housebound, said her husband, Brian, who took over the grocery shopping because his spouse wouldn’t have been able to use the debit machine or fish out the necessary cash from her wallet.

“We’ve had to decline invitations to dinner, to go out to meals with people, to go to shows with other people and so on,” he said, lamenting how the condition has stolen the joy of socializing from his gregarious wife’s life.

Smith suffers from “essential tremor,” a common neurological condition that often runs in families. Her symptoms began in her early 30s, mostly affecting her right hand, but also causing her head to quiver and her voice to sound tremulous.

“I come from a family where the familial tremor was evident,” Smith, a British-born former nurse, said from her home in Bobcaygeon, Ont. “I saw my father, poor man, trying to drink from cups of tea and pouring it all over him, and that made me very conscious of the fact that something has to be done about this condition.”

In fact, a number of surgical techniques are being used to quiet essential tremor. Deep brain stimulation, for instance, involves implanting electrodes in the brain to produce tiny electrical shocks that regulate abnormal impulses. However, such surgeries require drilling through the skull and accessing the brain with fine probes, raising the risk of hemorrhage, infection and collateral damage to critical tissue.

But doctors say a relatively new procedure — called MRI-guided focused ultrasound — is non-invasive. And a new study published Wednesday in the New England Journal of Medicine shows the technique is both safe and effective in reducing quaking hands in people with essential tremor.

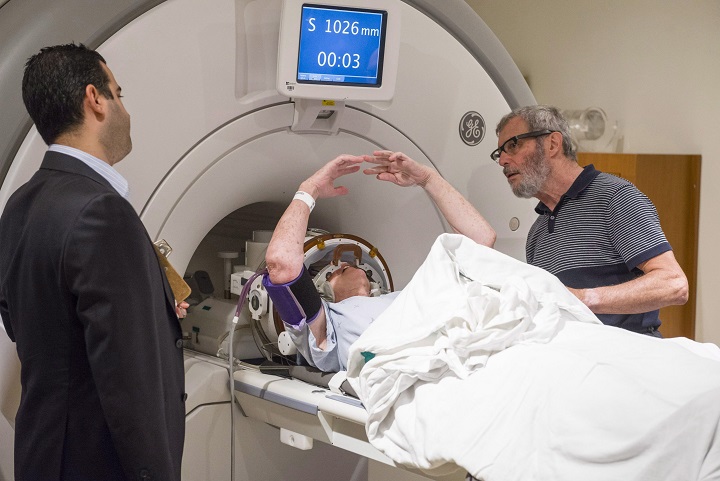

The patient, whose shaved head is fitted with a halo-like device, lies awake inside an MRI scanner, which transmits images from deep inside the brain onto a computer screen, allowing doctors to pinpoint the area in the thalamus where essential tremor originates.

Get weekly health news

With the exact spot identified, doctors zap the head-of-a-pin-sized target with precisely focused ultrasound beams, which produce enough heat to burn out the tissue. Following each “sonication,” the patient’s tremors progressively diminish.

“After treatment, if things go well, we see significant improvement in their ability to drink from a cup, eat soup, dress themselves, take care of themselves, and in many cases resume those activities that they had to abandon as a result of their tremor,” said Dr. Nir Lipsman, a neurosurgeon at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto.

READ MORE: Google debuts a spoon that steadies tremors

Lipsman is the co-principal investigator of the NEJM study, an international clinical trial that compared MRI-guided focused ultrasound against a sham procedure in 76 patients with moderate to severe essential tremor affecting the hands and arms, which had not responded to drug treatment.

Patients were randomly assigned to receive either ultrasound or the placebo treatment, in which no acoustic energy was delivered to the brain. Three months later, all the patients were videotaped doing various tasks and their tremor assessed by independent neurologists unaware of which patients had received which procedure.

The results were significant, said Lipsman. “In the (treatment) group, we saw almost a 50 per cent reduction in tremor in the treated arm. In the sham group, it was less than one per cent.”

At 12 months, the effects had worn off slightly, with patients on average exhibiting a 40 per cent alleviation of their tremor, a dip Lipsman said also occurs with deep brain stimulation and other open-brain techniques.

There were some side-effects: 36 per cent of patients experienced some gait disturbance and 38 per cent reported numbness in the hand, but those effects diminished after a year, to nine per cent and 14 per cent, respectively.

“What we hope is that any side-effects that we see actually go away with time,” he said.

“Our ultimate goal is to reduce the risk to zero and make this as safe a procedure as possible, while retaining its benefits.”

Dr. Kullervo Hynynen, director of physical sciences at the Sunnybrook Research Institute, developed the idea of pairing MRI with focused ultrasound while at the University of Arizona in the early 1990s. He has worked with industry partner Insightec for almost two decades to develop the technology.

“Brain treatments are very difficult currently and invasive brain surgery has lots of side-effects,” said Hynynen, noting that researchers around the world are exploring whether the technology could be used to treat other diseases, such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s, epilepsy and brain tumours.

“This device will open up a new era that will revolutionize the way brain diseases will be treated, eventually benefiting millions of patients,” he predicted.

Noreen Smith is already a believer.

Late last week, she travelled to Sunnybrook, where Lipsman’s team guided Smith through the procedure.

“Somebody said I broke into a dance. I did feel like dancing because it’s been many years since I could really use my hand to write properly … it’s amazing to be able to write again,” said a wonder-struck Smith.

“One thing I did yesterday is I filled out my weekend crossword. Also, I was able to apply my makeup without running the risk of poking myself in the eye.”

She’s excited about taking up her charcoal pencil to sketch again and looking forward to having friends over for dinner.

“And I know when I go out for a cup of coffee with my husband, he’s not going to have to hold the cup anymore,” said Smith, declaring her hand “beautiful. It’s like it was when I was 10 years old.”

Her husband, his dry sense of humour belying his delight at what he called a treatment “verging on the miraculous,” conceded that one kind of embarrassment has been replaced by another.

“In the past, I had to sort of physically hold her cup for her,” he said.

“And now I’m embarrassed because we’re sitting in a Tim Hortons or something, which is not totally empty — and she’s holding her hand up and saying: ‘Look, Brian! Look, Brian!’

“The papal blessing to everybody.”

Comments