Here’s why you need to start paying attention to Google Maps Timeline, an obscure Google feature you’ve probably never heard of.

I went over to a friend’s house a few days ago.

I arrived at 8:51 p.m. after a six-minute walk, and sat in the back yard until 10:11, a total of 80 minutes.

I don’t usually keep track of my life at this level of detail. But it turns out that between them, Google and my Android phone do.

Since April, when I got the phone and activated the Google Maps app, the phone has been reporting my comings and goings, all of which are mapped and are visible if I’m logged in to my Google account. Have a look at your version — there may be data on you.

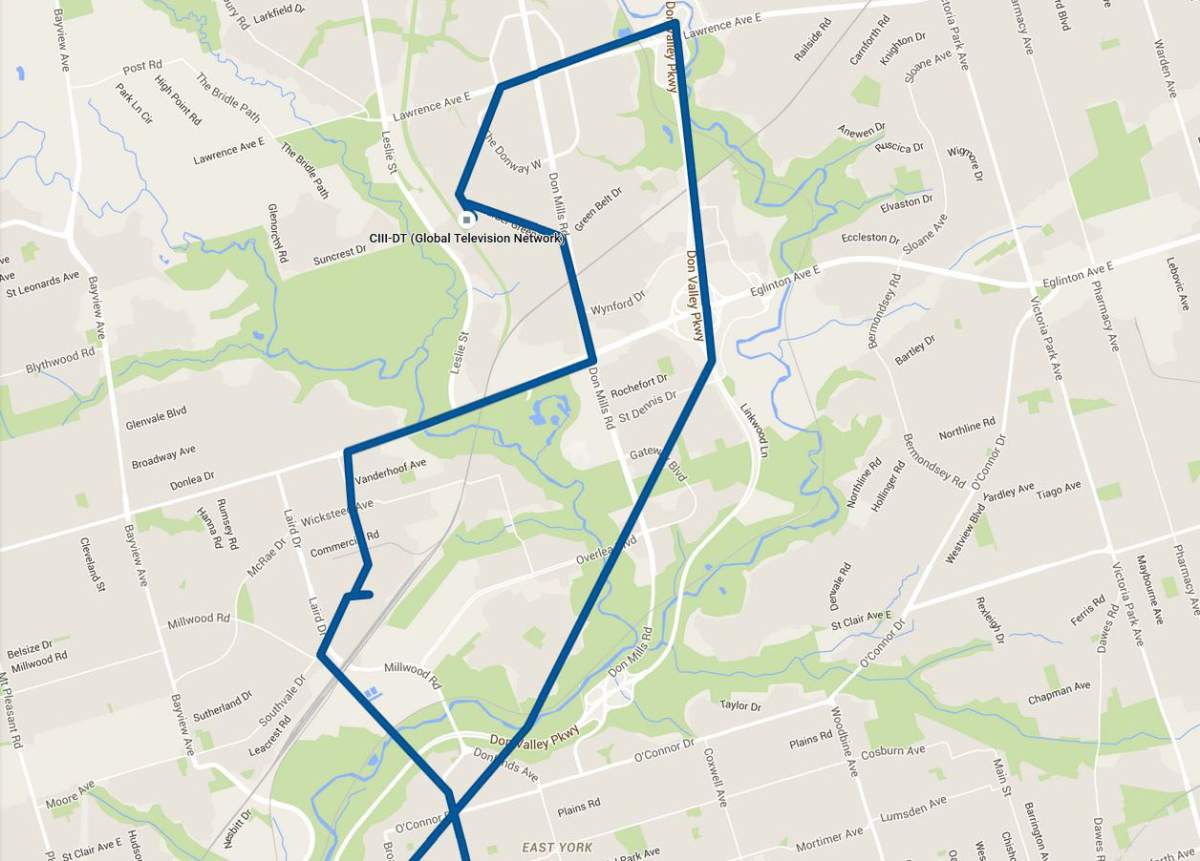

Google Maps Timeline, a feature that launched last summer, has tracked essentially all my movements since April 5. As far as I can tell it’s almost perfectly accurate in understanding whether I’ve been on foot, driving, or riding a bike.

The slower I travel, the more accurate the resulting maps are. When Toronto’s Don Valley Parkway is moving well, I’m tracked in quick, crude lines. In slow traffic, it becomes more precise.

How often does my phone connect to Google? It varies, spokesperson Aaron Brindle wrote in an e-mail.

“In order for your timeline to work properly, it collects data from a variety of sources such as GPS, WiFi, cell towers and device sensors like gyroscopes and accelerometers.”

Based on my own maps, though, it seems to be in the order of about two to five minutes, though I’ve found strings that are 20 seconds apart.

A couple of days after my 80-minute social call, our middle child, who’s seven, was excited about soccer practice. Her excitement couldn’t be contained, so I took her to the park early. Once there, we had to run around until things started, until all that energy could be channeled into organized sports. Here’s what Google made of it (light blue lines only):

As with so many things that affect our digital privacy, I apparently agreed to all this tracking, but without visualizing what my agreement would mean. It happened when I was setting up the phone and trying to get Google’s map app to work back in April.

“You must opt-in to turn on Location History for your Google account, and turn on each signed-in device that you want to use to send location reports to Location History,” Brindle wrote. “Location History is turned off by default.”

Can I trust Google with all this data I didn’t know was being gathered? For the sake of argument, let’s say the answer is yes.

Get breaking National news

A search for “google maps timeline” creepy gets dozens of results. I see the point, and somewhat agree, but on the other hand we have to give Google credit for transparency.

READ MORE: Does your phone help build Google’s traffic maps? (And is that bad?)

We sacrifice our online privacy on many different kinds of altars, but I’ve never seen a company visualize in such detail what data they were collecting, and explain exactly how to turn it off (which is easy to do).

The bigger problem, though, is this.

Even though we try to safeguard the dozens of passwords we accumulate in our digital life, our security is never going to be perfect. It’s easy to remember simple passwords, easy to rarely change them, easy to let a web browser remember them. Bad habits make busy lives a bit smoother, and they don’t matter, until they do.

The problem with Timeline is that anyone who gets hold of my Google username and password would have access not just to my email, but also to a detailed record of all of my physical movements. They could also use the Timeline feature that lets users export your geospatial data as a .kml file, and look at it in Google Earth, where it will play as an animation. So a single compromise of the Google account could lead to a permanent compromise of the data and a user’s past whereabouts.

With this in mind, let’s read this e-mailed statement from Google explaining the purpose of Timeline:

Your Timeline in Google Maps helps you easily remember and visualize the places you’ve been on a given day, month or year — providing a useful map of your life. This feature helps you visualize your real-world routines, easily view the trips you’ve taken and get a glimpse of the places you spend your time.

Now, let’s change a few pronouns around. I’ll use myself as an example.

Cain’s Timeline in Google Maps helps you easily visualize the places he has been on a given day, month or year — providing a useful map of his life. This feature helps you visualize his real-world routines, easily view the trips he’s taken and get a glimpse of the places he spends his time.

Not surprisingly, police have started to explore the possibilities. Earlier this year, the FBI served Google with a warrant in which they sought Android location data which they hoped would place a California man they were investigating for bank robbery at the scene of the crime.

The data should be precise enough to place Timothy Graham in the Bank of America in Ramona, Calif. on the day in question, supposing he robbed the bank and was dumb enough to bring his phone along as well as the “painter’s mask, hat and glasses” that witnesses described to police.

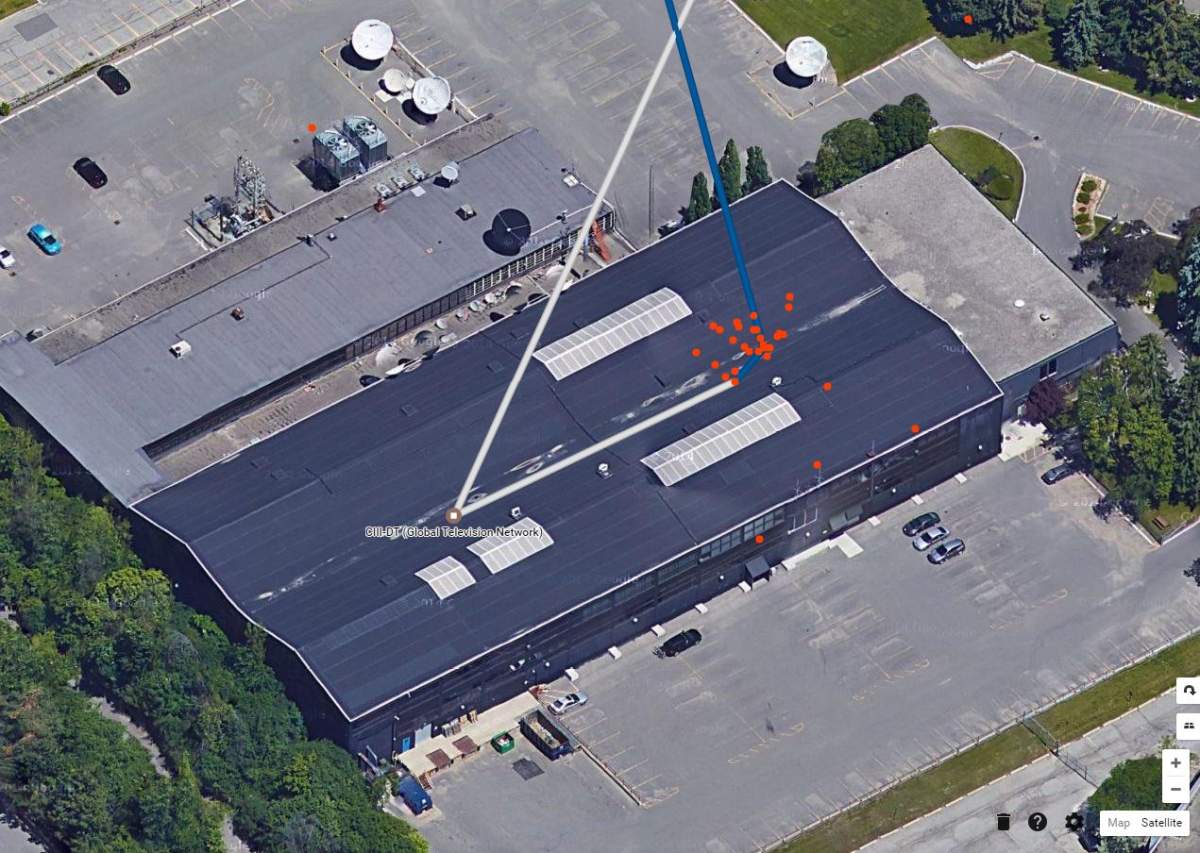

Here’s where I spent the day Tuesday, in Global’s Toronto newsroom, as my phone checked in with Google over and over again. That pretty much is where I sit, give or take five metres or so.

In the meantime, Timeline lets users edit or correct their data, remove dates — or just delete the whole thing entirely.

There is no real down side, Brindle says, unless you find Timeline itself useful. Google’s other location-based features will all still work.

Timeline does have a feature that alerts you to traffic problems on your usual commute, once it learns your normal route. It can also automatically generate a photo gallery if you go on vacation.

We’re not good at navigating the new world that our devices offer us, at least if we’re trying to hold on to the last shreds of privacy that are left to us.

“We have this consent model, but the consent model doesn’t work, because people don’t know what they’re consenting to,” University of Toronto law professor Lisa Austin said when we started writing about digital privacy. “It’s impossible for the average person to understand this actually, just in terms of information overload and the implications of it.”

“These companies, God knows what half of them do with your information, because we’re not reading these policies. We don’t know what we’re authorizing them to do, let alone what they’re actually following what they say they’re doing.”

VIDEO: Have you ever wondered how Google Maps is able to show you traffic patterns? One expert is worried it could be invading your privacy.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.