There’s a man in a North American city with a profile on OKCupid. We won’t be more specific.

He seems like a nice enough guy, if his profile is anything to go by. He reads widely, has interesting musical tastes, works in IT, but worries that that will make him seem nerdy. He’s put lots of thought into his profile.

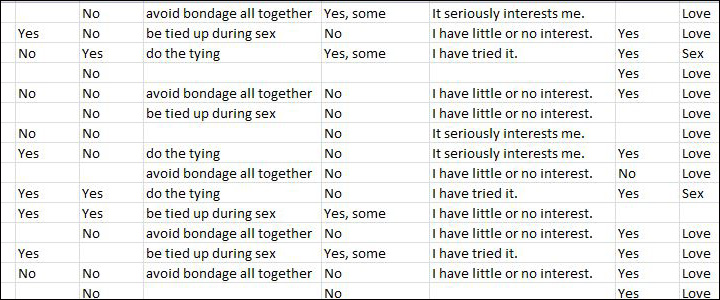

What’s not visible on his public profile, but is visible to me, is that while he’s been on OKCupid he’s answered 742 questions covering his religious and political views, openness to a range of sexual practices (he likes to be tied up and experience pain during sex — ‘some,’ but not ‘lots and lots’) and experience with drugs.

These may well be things which he would want to unfold in his own good time with a new partner, or perhaps not at all. TMI on a first date, let alone before.

But that may not be a choice he gets to make.

Two Danish graduate students scraped user data from the popular dating site for a psychology paper late last year and early this year, successfully downloading information on over 60,000 OKCupid users worldwide. Over 1,800 said they were in Canadian cities.

The data includes detailed information on site users’ sexual preferences, political opinions and personal habits which isn’t visible on their public profiles.

In their paper, Emil Kirkegaard and Julius Bjerrekær they were trying to use OKCupid data to measure its users’ cognitive ability.

“We are not interested in any more media attention because we’d rather work on science,” Kirkegaard said in an e-mail.

For a period of about a week, Kirkegaard and Bjerrekær made at least some of their data available for download.

“This was a violation of our terms of service and we sent a take-down notice,” OKCupid spokesperson Matthew Traub wrote in an e-mail. “They appear to have complied.”

Global News successfully downloaded a copy from a mirror site on Tuesday.

Kirkegaard and Bjerrekær only downloaded the user data of people who had answered a large number of questions. It’s a small (but active) subset of the site’s total user population — at a specific time on Tuesday, OKCupid said that about 130,000 people were actively using the site.

Get breaking National news

The data contains users’ answers to up to 2,622 questions, some more personal than others, including:

- Have you been faithful in all of your past relationships?

- Not to be racist but which ethnicity do you find to be most attractive?

- Imagine you are very interested in a long-term relationship with someone. Would it be worse if they wanted you only for casual sex or if they were not interested in sex with you at all?

- Have you ever traded a lover sexual favors for something you wanted?

- Would you ever consider having sex in a church?

Many OKCupid users answered a large number of questions about their sexual preferences. Much of that data is now public, though in most cases not with real names attached.

The data was scraped, not hacked, meaning that they downloaded data that was in principle public, but not necessarily in the way the site’s owner arranged for it to happen. For example, if someone wanted to study a 10,000-line searchable database and found the search function restrictive, they could find a way of downloading it.

Logged in to the site, Kirkegaard and Bjerrekær could see profiles one by one, but their bot, a simple computer program for repetitive operations, could download them in bulk.

“Some may object to the ethics of gathering and releasing this data,” they wrote. “However, all the data found in the dataset are or were already publicly available, so releasing this dataset merely presents it in a more useful form.”

Traub did not respond to questions about whether the scrape being possible in the first place reflected badly on OKCupid’s approach to data security, or how the company’s data practices had changed in response.

An OKCupid member’s answers to the questions aren’t normally visible on the site. However, by pasting a username from the Danish students’ spreadsheet to the URL for an OKCupid profile (https://www.okcupid.com/profile/username), it’s possible to easily cross-reference a detailed catalogue of highly personal information to the public profile, which includes profile pictures.

It would not be difficult, for example, to produce a list of the URLs of the profile pages of OKCupid members who say they would like to have sex in churches, broken down by community.

“If it was me, I would take my profile down. I would just get the hell out of there,” says former Ontario privacy commissioner Ann Cavoukian. “This could happen again, and you know your information is accessible now. “

“What OKCupid has to understand is that the expectations of the community of people subscribing to this service is not one where everything is going to be identifiable,” Cavoukian says. “Their expectation was that their data, their very personal data, would be secure, and would not be accessible until they did a more deep dive with a particular individual, and they both wanted it to go in that direction.”

(Data journalism, an area of journalism which uses electronic data to find stories, sometimes uses scraping techniques similar to Kirkegaard and Bjerrekær’s, though more usually from public-sector sites, in situations where there are no privacy or consent issues.)

In the scraped data, there is far less information related to people’ real identities than there was in the Ashley Madison data leaked last August. That data contained detailed map references of users.

With enough work, however, it would be possible to identify a significant number of individuals, says Scott Weingart, a digital humanities specialist at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, Pa..

“While the OkC data do not contain real names, they contain many ‘quasi-identifiers,’ Weingart wrote in an e-mail. “These are things that, when combined, can lead to a unique person.”

“With that knowledge, a malicious user could then comb through their profile information, gathering their sexual orientation, interests, and so forth. It’d be a stalker’s dream and a user’s nightmare.”

Danish privacy authorities are investigating the scrape, according to reports.

Tue, Jul 29: Online news producer Paula Baker talks about the OKCupid’s decision to test some theories on their unsuspecting users.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.