Camille Runke had every right to expect the law to protect her. She had a protection order against her estranged husband and had almost regular contact with Winnipeg police.

But when she was shot at close range with a shotgun outside her work on Oct. 30, 2015, her name was added to a long list of women killed every year in Canada by someone they used to love.

READ MORE: Camille Runke’s family suggests ankle bracelets for suspected stalkers

“We want the laws to change,” Jenn Noone, a friend of Runke’s in Winnipeg, said. “And if it’s going to take Cam’s story to do it, we’re going to do it.”

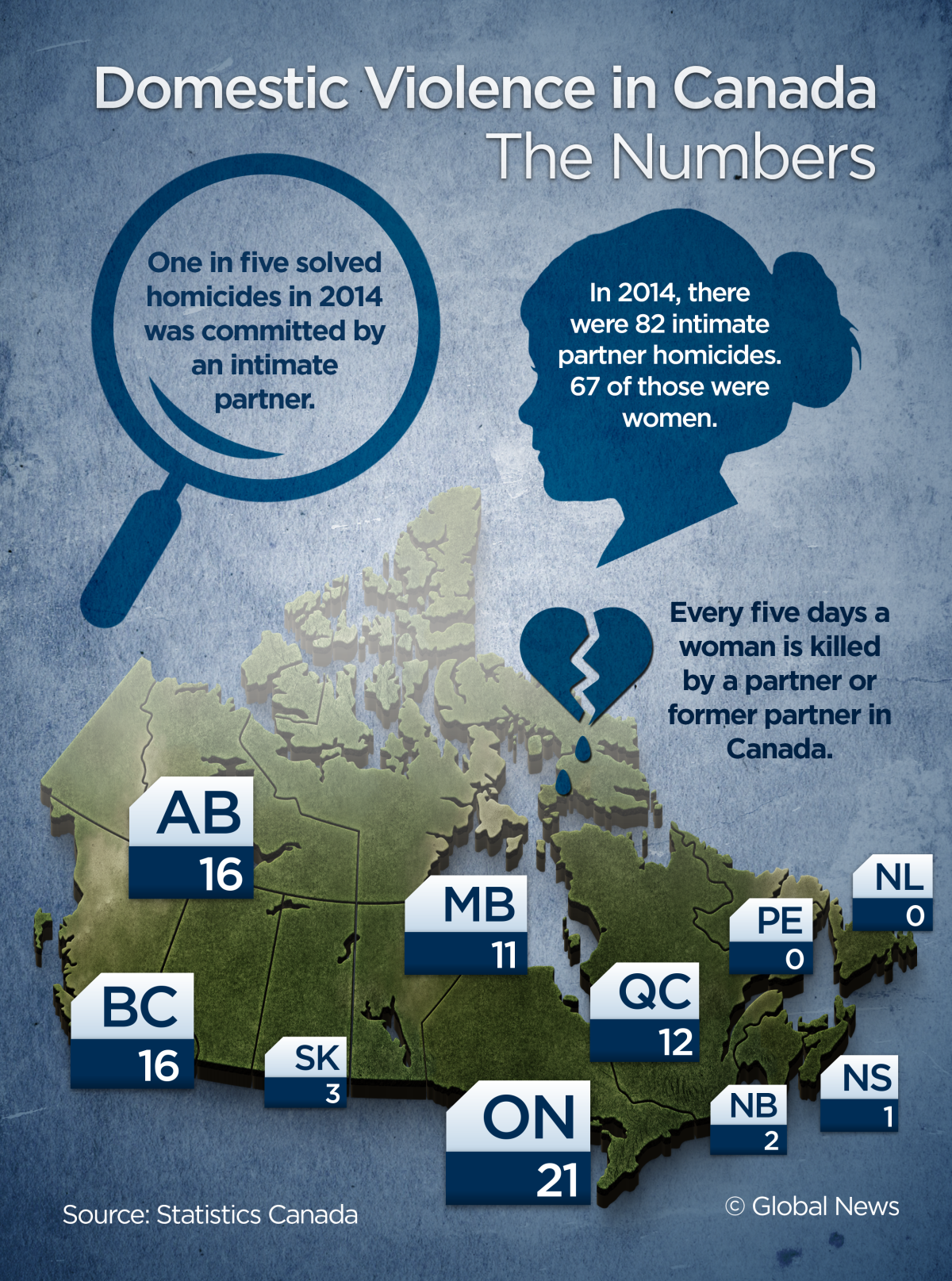

Every five days a woman in Canada is killed by her partner or former partner.

In 2014, there were 82 intimate-partner homicides; 67 of the victims were women. Eleven were in Manitoba. And two murders last October in Winnipeg have ignited the conversation about domestic violence and intimate-partner violence. Runke’s is one of those.

Over the period of five months, Runke had called police 22 times, reporting smashed windows, slashed tires and threatening messages. She suspected her estranged husband, Kevin Runke, was stalking and harassing her.

Camille, 49, and Kevin Runke, 44, were married in 2013. They seemed like a couple in love. But in the spring of 2015, Camille caught Kevin cheating and the marriage was over. Shortly after, Camille started reporting the incidents.

In July 2015, Camille also applied for a protection order. On her application she wrote “he has a rifle.”

READ MORE: ‘He finally got her, we knew’: Friends of St. Boniface murder victim want change

Protection orders are meant to be one of the tools designed to keep a woman safe. Breaching a protection order is a criminal act and is supposed to help police get offenders off the street faster.

If Kevin came within a certain distance, attempted to contact Camille or approached her property, he was breaking the law. The problem was gathering the evidence. Camille called police a dozen times after she got her protection order.

“The challenge with the Camille case is the nature of what she was calling us for,” Danny Smyth, deputy chief of the Winnipeg Police Service, said.

WATCH BELOW: A preview for 16×9’s “When the Law isn’t Enough”

_tnb_1.jpg?w=1040&quality=70&strip=all)

“Largely, they were property-related offences that had occurred in the middle of the night when no one witnessed them.”

Smyth says they suspected Kevin and spoke to him on numerous occasions, but there was little else they could do. They needed evidence.

Camille put cameras up around her home, she got a secret cellphone and told neighbours to keep watch in an attempt to gather evidence.

“And she was scared. She was losing weight. She was getting sick over this,” Maddie Laberge, Camille’s sister, said.

“That’s why protection orders were put in place,” Anna Pazdzierski, manager of Nova House, a shelter for abused women, said. “Who goes out there and dumps nails in front of a person’s vehicle? These are not things that normal people do.”

The Winnipeg Police Service receives over 14,000 calls a year for domestic violence. Last year, the province also received over 1,200 applications for protection orders. Over half of them were denied.

Selena Rose Keeper, 20, of Winnipeg was beaten to death on Oct. 8, 2015. She had applied for a protection order against Ray William Everett, 20. On it she wrote “I want to keep Ray away from me.”

Her application was denied. Everett has been charged with second-degree murder.

But getting a protection order doesn’t guarantee safety.

“A protection order’s just a piece of paper,” Pazdzierski said. “We need to realize that women fear, we need to respond to those protection orders. We need to take them seriously.”

In the case of Camille Runke, who called police 22 times including a dozen times after her protection order was in place, police said they needed evidence to arrest Kevin.

“He (was) covering himself very well,” Laberge said. “So he has sort of figured out how to do this by flying under the radar.”

Kevin Runke was charged with breaching the order when he changed addresses, but not for actions against Camille.

Statistics obtained by 16×9 reveal that if police had arrested Kevin Runke for breaching the protection order, the chances of conviction would be good.

“We know that if a person is charged with a breach of a prevention order their likelihood of being convicted is much greater than the likelihood of all other persons charged for a domestic matter,” Dr. Jane Ursel from the University of Manitoba said. “So, rather than a likelihood of 50 per cent conviction or 55, it’s more likely to vary between 65 to 70 per cent.”

But people have to be charged with breaches and Pazdzierski says that is not happening.

“In Canada, we spend $7.4 billion per year on family violence, domestic violence. That’s our court systems, shelters, the police, everybody who has to respond to domestic violence,” Pazdzierski said.

A week before Camille Runke’s murder, police had recommended criminal harassment charges against Kevin Runke.

READ MORE: Winnipeg police confirm husband of woman murdered in St. Boniface is dead

Kevin killed himself three days after Camille’s murder.

“There’re limitations to what the law will allow without real evidence,” Smyth said. “That’s why I think intervention and prevention programs still have to be factored into this. We can’t just respond and arrest our way out of this problem.”

Manitoba has now introduced legislation imposing a mandatory firearm ban on all protection orders, and making orders easier to get. It is also testing GPS monitoring and how it can be used in cases of domestic violence.

But laws don’t change behaviour.

“He wasn’t getting counselling. He wasn’t getting help. He wasn’t getting thrown in jail. You know, it was just this perfect storm. And I really feel like we could’ve done something more,” Laberge said, hoping her sister’s death isn’t in vain.

16×9’s “When the Law isn’t Enough” airs Saturday, Feb. 20, 2016.

Comments