WATCH ABOVE: Members of the Global News team read questions students submitted to their sex ed classes. (Disclaimer: We don’t give great advice — but you can find better answers here)

Sex, sexuality and sexual health can be fraught topics to broach in the classroom. But much trickier than any curricular updates is answering students’ questions — the anonymous, curious, often awkwardly written queries young people submit over the course of their sex ed lessons.

“Answering the questions is the most challenging part of a program,” Kim Martyn said.

“Teachers are used to getting a curriculum and looking at it and then presenting it. That’s what they do.

“But the questions, particularly for this topic, are a whole other challenge: ‘How do I answer? Do I answer this? To what extent do I give detail?'”

READ MORE: Can Ontario give its sex ed a 21st-Century makeover?

She should know: The sexual health promoter with Toronto Public Health has been teaching students about sex — and teaching teachers how to approach sex education — for upwards of three decades, covering as many as 100 classes a year.

“I haven’t gotten sick of it. Isn’t that crazy?”

“When you sit there and you see the kids who start off nervous, shy, worried, and then you see them open up, you see… their faces relax and feeling just better about themselves. It’s huge.”

And with the new Ontario curriculum going into effect this year, she and her colleagues are likely to field plenty of questions.

“We’re expecting to be quite busy,” she said.

Not because there’s a slew of new content — contrary to much of the consternation around the new curriculum, it’s neither radical nor untested — but because much of the content is shifting down a grade, and there’s more of an emphasis on issues such as equity.

“Whether that’s gender, discussing maleness and femaleness, or bullying, homophobia, racism … it’s in all components of the curriculum.”

Ontario’s new sex ed curriculum has sparked vocal protests from people who argue it’s radical and sexualizes young children. But public health officials and educators note the province’s existing sex ed is 17 years out of date, and woefully behind other jurisdictions. They argue that has real consequences for young people trying to come to terms with their own identities, often in the face of bullying or ostracization.

READ MORE: What’s the evidence behind Ontario’s new sex ed curriculum?

Martyn expects many of the calls for advice and assistance to come later in the school year: Most teachers don’t do their sex ed programs until the spring.

“I think teachers want to establish a rapport with their class,” she said.

Get weekly health news

“But the teachers who do this in the fall… the feedback we get is, this really helps to establish a rapport: The students see this teacher is askable and they can make the classroom into a safe place to talk about these trickier subjects.”

Some of what Martyn and her colleagues go over are the basics.

“A lot of people get gender and orientation confused… So just helping us be clear about what those things are, what they mean.”

But a lot of her instruction is more what she calls the “soft” skills and information — how to make the discussions comfortable, safe, accepting, informative.

That’s why the way you treat kids’ sex questions can be so important.

“What might be the motivation for a student asking the question?”

READ MORE: Sex education compared across Canada

Martyn has four rough categories of questions:

- The “Am I normal?” questions.

- The “Test the teacher” questions, which may ask about the teachers’ own sexual experience (and which is always politely dismissed: “We’re not here to talk about anyone’s private life”).

- The “I’ve heard…” questions, which tend to stem from whatever outlandish-seeming reality TV show the children have seen or heard of.

- The “This is something that’s worrying me” questions.

In answering the questions, Martyn recommends teachers consider their students’ self-esteem. There really can’t be any stupid questions.

“Regardless of why they’re asking, even if it’s ‘How many times have you had sex?’ that child is maybe embarrassed by the whole topic or trying to hide their embarrassment or show off for their peers,” she said.

“We want to make sure their self-esteem is acknowledged and really boosted regardless.”

And answering these questions is about more than giving the facts, Martyn said: She’ll try to get teachers to reinforce issues around consent, respect and self-care, as well.

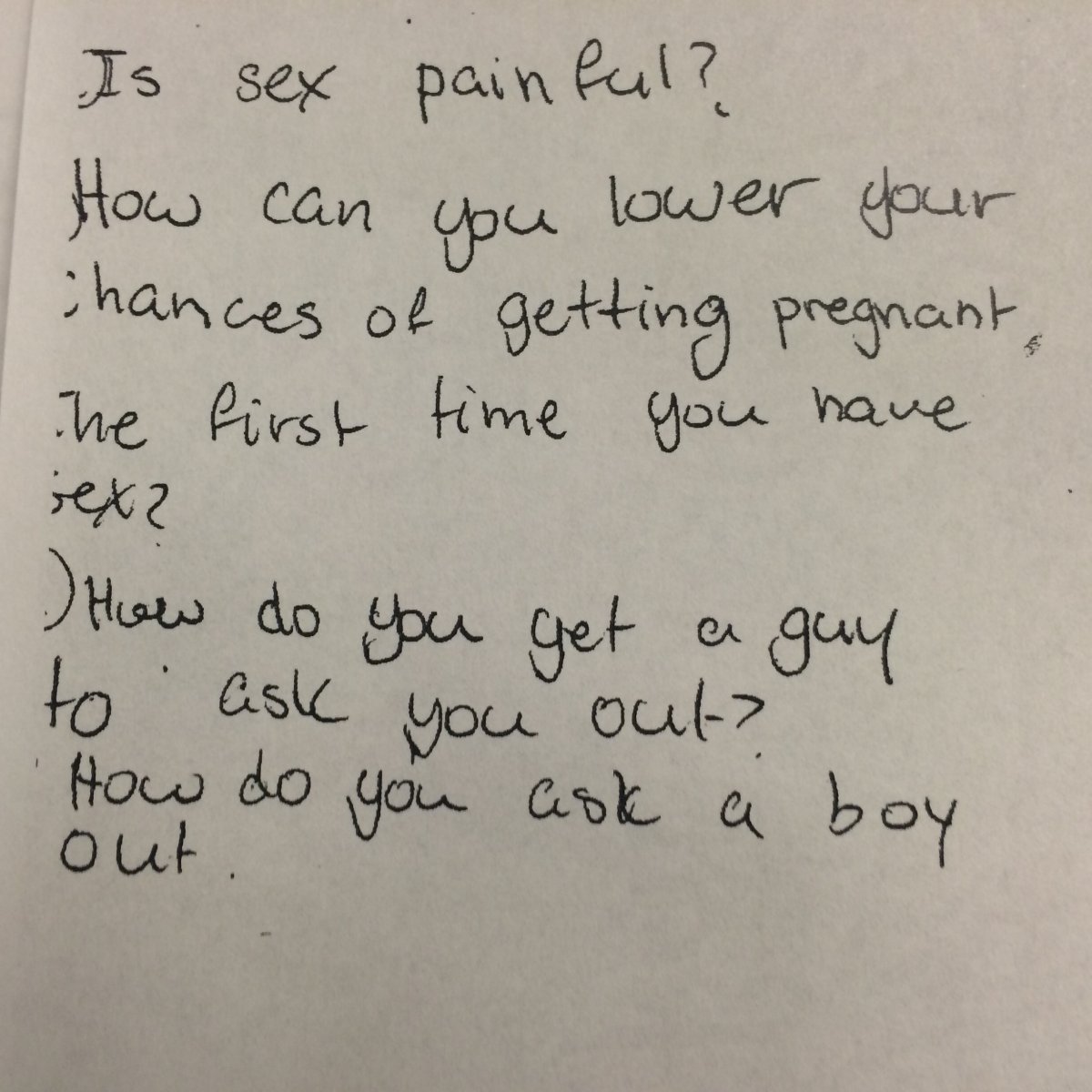

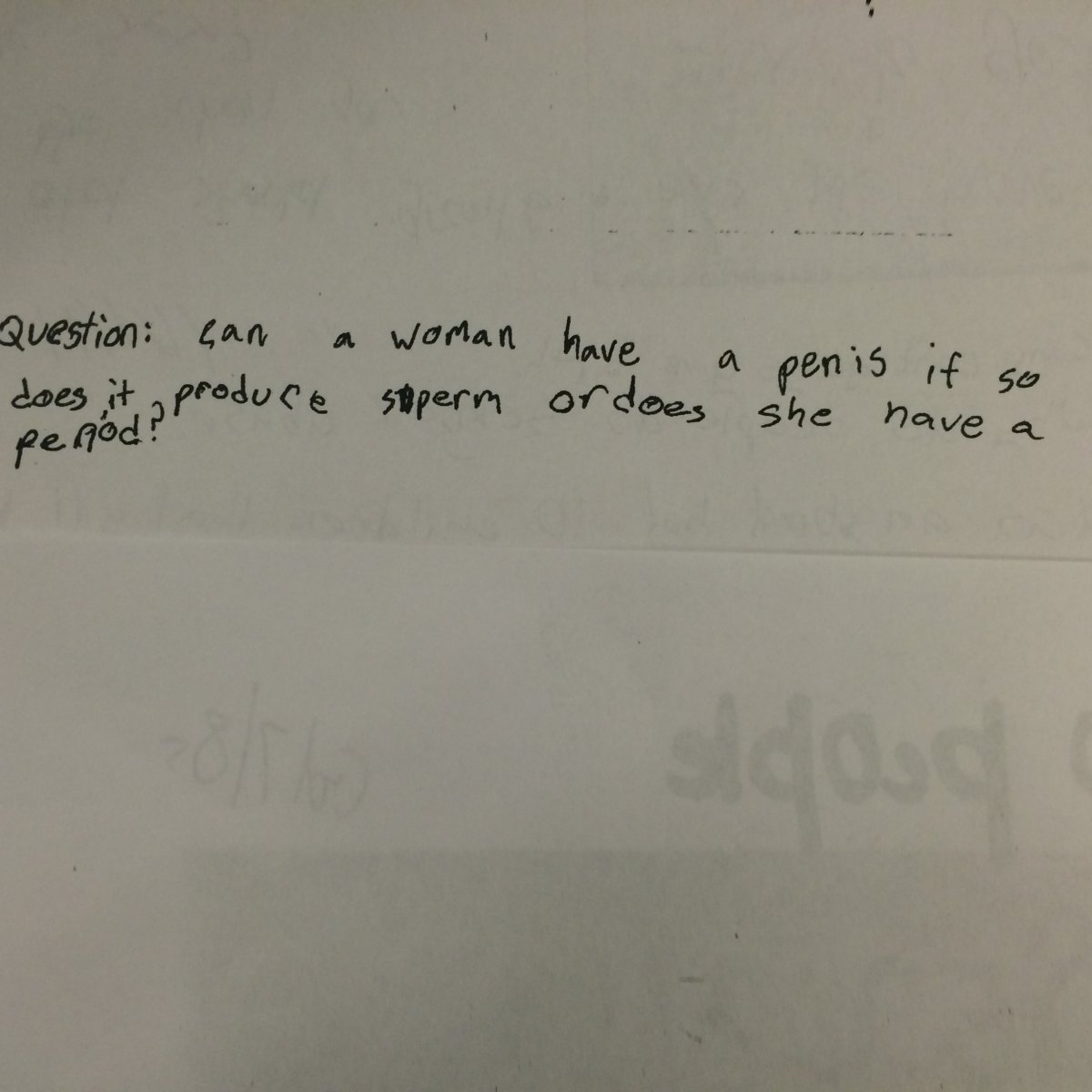

GALLERY: Click through to see the handwritten questions kids asked in their sex ed classes

In the case of the — very common — question as to whether STIs can be spread through oral sex, a teacher would give the answer “yes, they can” but would also “make sure to include stuff on consent,” Martyn said.

“Any time anyone’s doing anything sexual with someone, both people need to be fully aware of the consequences and also fully giving consent. And what does consent mean? What does it look like?”

And while teachers should answer all questions frankly and openly, there are age-appropriate ways to do so, Martyn notes.

The question “Why do people watch porn?” or “What is porn?” elicits very different answers depending on the grade.

- Single-family home starts hit 69-year low in new Ontario housing data

- ‘Something we see in TV and movies’: Toronto police showcase guns used in studio shootout

- Community, family set to hold vigil for man fatally shot by Hamilton police

- Man dead in stabbing following argument in downtown Toronto: police

To a Grade 5 class, Martyn said, a teacher might say:

“It’s produced by adults for adults and you have to be over 18. And it’s not real: Much of it is people who stage things, just like a movie. And often, in it, people don’t have loving, caring relationships…

“I want them, when they’re looking at it, to have some critical skills: ‘Oh yeah, that woman looks like she’s being forced. She’s just acting, but it’s not okay.”

With a group of high school kids, on the other hand, the discussion can be much more involved: Is it an industry like any other? Is it inherently exploitative?

“I would go into details about how almost never is there safer sex shown, and so what do you think happens in real life with those actors? Are they using condoms that we don’t see? And how do you think that impacts people watching it when there’s never safer sex being displayed?’

And yes, she often gets questions from kids who think there’s something wrong with homosexuality. They underscore the importance of these sessions, Martyn said.

“We would gently sort of say, yeah, we hear different things from our families, from our friends, from our faith centres.

“And part of growing up is hearing about different people’s opinions and views on things in the world. And then as you grow up you get to think about these things for yourself.”

Have the questions kids ask changed in the 30 years Martyn’s taught sex ed? Kind of: There are more people asking about HPV thanks to publicity and education around the vaccine. More people ask about same-sex relationships and families because they’re seen as more mainstream.

And while there’s always been the student asking about porn, now there’s much more widespread awareness of more aspects of sexuality than before.

But the existence of questions that run the gamut from innocent to explicit reinforces the need to teach kids about sex, she said.

“This isn’t being fabricated or imposed. This is coming from what we know that students are asking.”

READ MORE: Ontario releases sex ed ad

Comments