EDMONTON – Most 16-year-olds take a few things for granted: turning on the lights or the TV, texting friends and surfing the web.

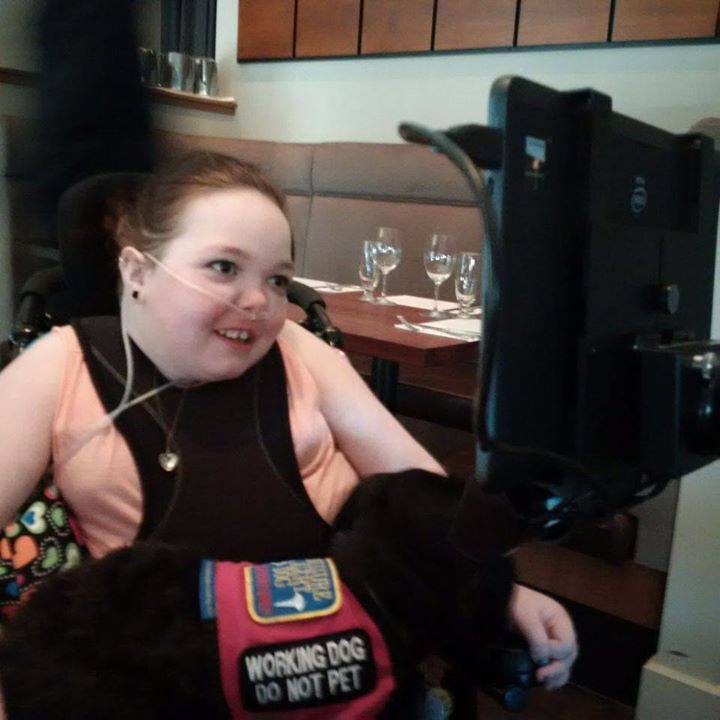

Jo Picard can now do those things on her own for the first time, thanks to a new device that tracks her eye movements.

Picard has Rett Syndrome, a neurological condition that limits her speech and movement. Until now, she has had a modified commercial tablet to communicate, but its usefulness is limited, especially compared to the new one.

“I feel my device has changed the perception of others and how they treat me,” Jo says. “People talk to me instead of at me. My wheelchair and disability become irrelevant; I am a person, a human being. And for the first time, I feel that is what they see first. I can tell my mom, dad, and sister I love them, something that I hope they knew before, but it was powerful to be able to express it without needing assistance.”

But Jo will have to give the new device back at the end of a trial period and wait for the Alberta government to approve funding for her own device. That could take months or even years, with no guarantee of success.

“The Charter of Rights and Freedoms states I have the right to freedom of speech, unless of course you have a disability,” Jo says. “And then I have to earn that right by waiting on wait lists for years only to prove I am worthy of a device. If they had this process for insulin pumps, my government would be crucified. Why is this process OK for those who need a communication device?”

- ‘She gets to be 10’: Ontario child’s heart donated to girl the same age

- Bird flu risk to humans an ‘enormous concern,’ WHO says. Here’s what to know

- Shoppers faces proposed class action over claims company is ‘abusive’ to pharmacists

- Most Canadian youth visit dentists, but lack of insurance a barrier

Alberta Health doesn’t cover devices as sophisticated or as expensive as the Tobii I-series device, which costs $20,000 to $30,000.

“For years, Rett Syndrome was seen as a disability where people didn’t have that cognitive ability to operate these things,” says Jo’s mother Simone Chalifoux. “What Jo is hoping to show is that she has that cognitive ability; she can read, she can write, she can text her friends, she can put things on Facebook, she can change the channel on the TV. She’s just locked into her body.

“We only get so many dollars to last through a year or five-year time period. So if you need to buy a new device, you’ve used all of your money in one shot and now you’ve got to wait another five years to have access to that again. What piece of equipment lasts five years? Not something that you’re bringing with you everywhere, that gets dropped or that maybe breaks.”

Chalifoux explains the issue is one that has affected many more families in similar situations. Many of these families have had to take out loans to modify their homes or for crucial medical expenses not covered by their health insurance or benefits – equipment their children need to use on a daily basis. This has put them in a position of having to turn to to wish organizations to fund communication devices.

“What that means is that child has to use up that wish, which could really be almost limitless, to have a voice,” she said.

Earlier this year, the United States introduced The Steve Gleason Act, which makes it mandatory for people with disabilities similar to Jo’s to receive access to the equipment they need. A similar law in Canada would mean that people with disabilities similar to Jo’s would be guaranteed to be supplied with eye-gaze devices instead of having to fight for them.

Comments